- Home |

- Search Results |

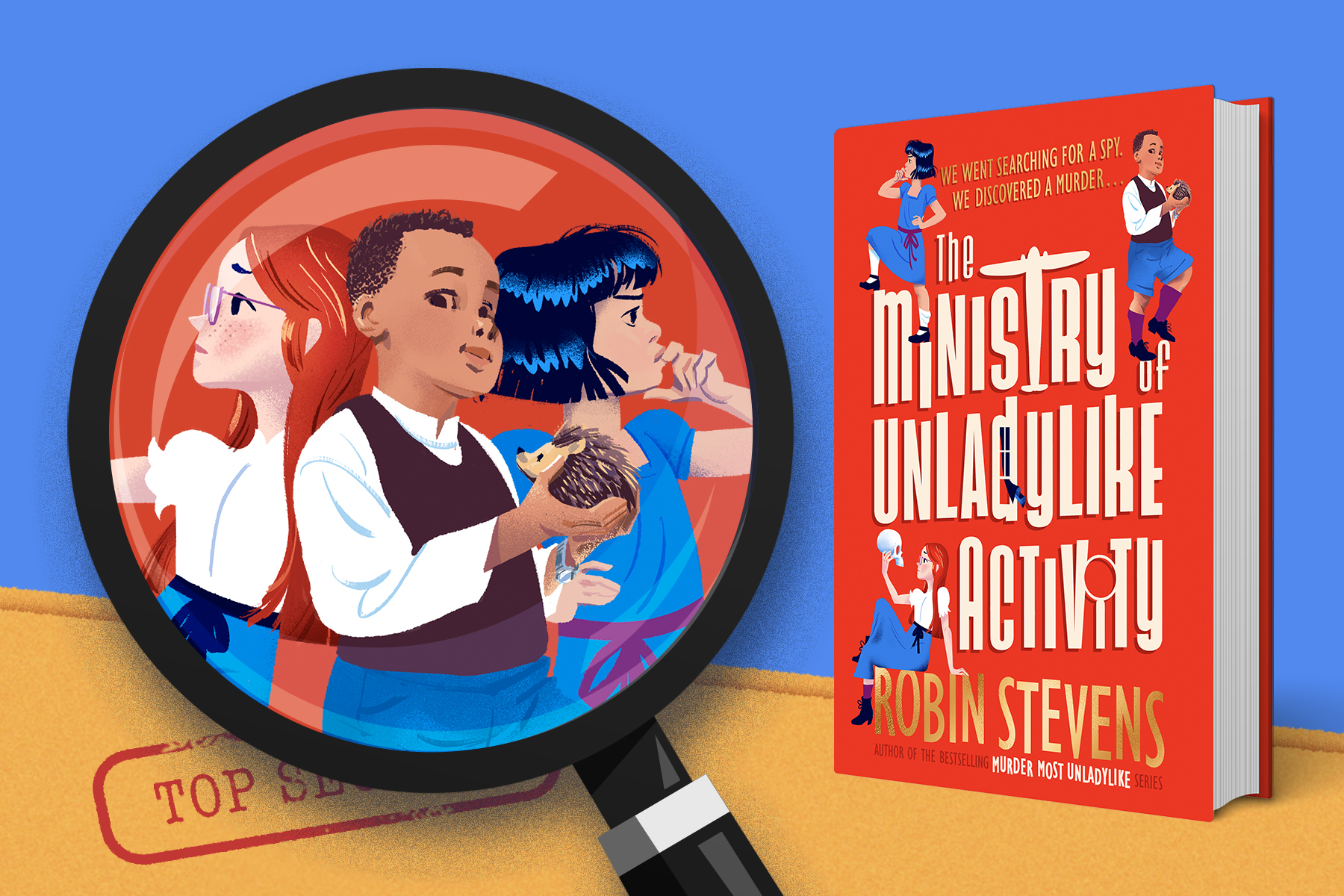

- The Ministry of Unladylike Activity by Robin Stevens

The Ministry of Unladylike Activity by Robin Stevens

It’s 1940 and Britain is at war. The British government have set up a secret arm to train spies called the Ministry of Unladylike Activity. And 10-year-old May Wong wants to join and help end the war. She knows she’d make the perfect spy. So, there’s only one thing for it – she must leave Deepdean and head to London…

1

From the report of May Wong, WOE operative, 18th December 1940

My name is May Wong. I am ten years old (nearly eleven), and I have become a spy in order to save the world. That is true and not an exaggeration. Anything can happen in a war, and anyone can be a hero.

And anyone can be evil too. When the war began, I thought that Nazis might look like the lizards who used to bask on the steps of our Big House, back in Hong Kong. I imagined them with scaly, flickering skin and yellow eyes. I thought that being evil must make you look evil.

But, now that I’m older, I’ve realized that evil can look like anything. Evil can look like a starchy governess, or a kind old lady, or the warden who comes round to check the blackout.

This is the story of how I – how we – uncovered a Nazi spy in England, solved a murder and joined the Ministry of Unladylike Activity. It was much harder than I expected. We had to be very clever, and, as usual, none of the grown-ups listened to us until it was almost too late. Grown-ups really are hopeless. But they’re listening now, at last, and they want to know everything that happened. That’s why I’m writing this.

By the way, this is the official version of the notes I took during our mission. I’m supposed to be using formal language, the way we’re taught at school, but I’ve decided that this is my report, and I’m going to tell it my own way. And that means explaining some things first.

The most important thing to know about me, apart from the fact that I am now a spy, is that I’m not supposed to be in England at all. I’m supposed to be living in Hong Kong, where I was born, with my mother and my father and my little brother, Teddy. But I came to England last year with Father and my second sister, Rose, to visit Deepdean School for Girls – the stupid English boarding school that Father planned for us to go to. And, while we were here, the war began.

Father went home as quick as he could to be with Ma Ma and Teddy, but he left me trapped in England with Rose and my biggest sister, Hazel. I can’t go back to Hong Kong until the war ends – so obviously the only thing I can do is make sure it ends as quickly as possible. I miss Ma Ma and I miss Teddy (even though he’s too small to be very interesting). I think I even miss Father, although he was the reason I got stuck in England in the first place, and the reason I have to go to Deepdean, which I hate.

Or at least I did go to Deepdean until I ran away to become a spy.

I ran away because I had to. There was no other choice. Everyone in my family – including Big Sister Hazel – thinks that I’m still a baby, but I’m not. The truth is that I can speak two entire languages and run for ten minutes without stopping and lie well enough to trick Father and the Deepdean mistresses. I can fight with a sword (or I could if someone would give me a real one – all I’ve practised with is a stick) and with my feet and my fists.

So I was sure that I’d be an excellent spy, if only someone would give me a chance.

You see, I knew a spy already: Hazel.

I am absolutely not making that up. It’s true.

And it’s hard when your sister has already done all the things you want to do. Hazel went to Deepdean once too, and she’s famous there, even now that she’s very old (nineteen). She loved school. And Rose, who is twelve, loves it as well. So, when I first decided I wanted to become a spy, I thought I had to love it too. I spent minutes and minutes on my school compositions, and I tried not to hit any of the other girls during Games, and I even gave Mariella Semple my jam roly-poly pudding at dinner. (I was sorry about that later – she didn’t even finish it. What a waste of jam roly-poly!) But it all just made me notice how much I hated school, even when I was trying.

So I decided to become a spy another way.

I asked Hazel how to do it, but she would never answer any of my questions. She wouldn’t even admit she was a spy, even though it was perfectly obvious.

And then I found the note in her handbag.

Obviously it wasn’t for me – I’m not stupid – and I shouldn’t have been looking in Hazel’s handbag in the first place. But I was bored, and I was cross, and sometimes I just do things without thinking about them. I only feel bad about them later.

It happened like this.

By September 1940, the war had been going on for a year, but you almost wouldn’t know it, living in Deepdean. Deepdean Park was full of sandbags, a bomb had fallen on the cinema by mistake (no one was hurt) and there was no cream on the cakes at the Willow Tea Rooms or soap powder at our boarding house to wash with. I didn’t care much about the soap, but I did about the cream. But that was really as far as it went. It wasn’t at all like war is in stories. The newsreels at the pictures, of cities in Europe falling and German soldiers marching and shooting, felt exciting but nearly as made up as the main feature. It sounds strange now that I know better, but I was... almost disappointed.

And then we began to hear stories about the Nazis crossing the Channel to flatten us like a thumb squashing a bug. Planes buzzed overhead every night, and every day the invasion seemed closer and closer. So, when Hazel came to Deepdean to take me and Rose out for tea, one weekend at the beginning of October, I decided I couldn’t wait any longer.

I asked and asked and asked Hazel about spying, and what it felt like to be in a real air raid, and how many people were dead in London, and whether it was true that the Germans were about to invade, and if so what were we going to do about it, until Rose got all wobbly and started to cry, and Hazel told me to stop. Rose had to sit down on a bench on Deepdean high street and put her head between her knees, hugging her gas-mask case, while Hazel patted her back and gave her a bullseye to suck. Hazel always has sweets in her pockets, even now they’re rationed. Spies get all the best things: another reason why I wanted to be one.

‘It’ll be all right,’ said Hazel, as a man in a Home Guard uniform walked by. ‘No one will hurt you, Rose, I promise. We’re prepared. We won’t let them come here.’

I didn’t see how she could promise something like that. It sounded like a grown-up lie. I picked up her handbag to look for more sweets. But what I found, instead, was a note.

It was scribbled all over with crossings-out, but circled at the bottom of it was a very simple message, underlined:

Your attendance is required for

training of the utmost importance.

The Ministry, 13 Great Russell Street, London,

4 p.m., Saturday 26th October 1940.

This looked important. I shoved it in my pocket just as Hazel turned to look at me.

‘Give me that,’ she said, and slid her handbag back onto her arm. So she hadn’t noticed what I’d taken. ‘Come on, who wants scones?’

I did, obviously. But, more than that, I wanted to find out what that message meant. It was spy business, I was sure of it. I knew that this was my chance to find out what Hazel was really doing, and help her do it.

I just had to run away from school first.

2

From the report of May Wong

The running-away part was easy in the end.

Everyone at Deepdean has stories about how hard it is to get away, and what a bad idea it is (the stories all end with the girl either getting detention for the rest of her life or falling over dead in a ditch). But actually all I had to do was leave our boarding house in the usual Saturday crocodile of girls, wait until we were almost at the park, and then pretend to be ill and have to go and sit down next to some sandbags. Eloise Barnes wanted to stay with me, but I told her that I thought I was going to be sick, and she squealed and scuttled away. As soon as she was gone, I ran as fast as I could to the train station.

I’d filled my gas-mask case with everything I’d need: some sweets, a manual about air raids, extra shoelaces (in case I needed to tie anyone up), a London A to Z, a small torch, and a spare pair of knickers. Once I’d done that, there was no room for my actual gas mask, so I’d hidden that under my dorm-room bed. I also had all the money I could find, most of which I’d had to pinch from Rose’s tuck box because I’d spent mine. I felt quite bad about that because Rose is a kind person and would have given it to me if I’d asked – but she’s also very honest, so if I had asked she’d have told Matron what I was up to.

I bought a half-fare to London, one way (because I was not planning on going back to Deepdean), and ducked into the loos to swap my uniform for my weekend dress, cardigan and hat. When the train came, I pretended to belong to an old woman with a crowd of children. I climbed aboard and sat in the blue half-light next to another woman in a siren suit (these are funny overalls that you’re supposed to wear over your clothes in case there’s an air raid, which just make people look like they’re about to go fix a car), watching out of the edge of the lowered blind as the train crept through the countryside. It was going slowly because there might be bombs on the line, and everywhere it stopped was a mystery, all the signs painted out and no announcements, in case of German spies. It already felt like I was part of a story.

Finally, we pulled into the big dome of Paddington station. I dodged round grown-ups in uniforms, and newspaper sellers, and came out onto a street full of red London buses that had advertisements for OXO cubes and powdered eggs on their sides.

I got on a bus that I knew from my A to Z would take me to Great Russell Street. I pretended to belong to another grown-up – it’s useful being little sometimes: no one thinks you could possibly plan anything yourself – and as the bus jolted its way through London I tried not to look shocked at what I saw out of the window.

I’d heard stories about the Blitz, how the whole city was lit up with fire every night, how the Germans had huge great big bombs that could crush whole houses to powder and peel the clothes right off the people who lived in them, but I thought it all sounded too big to be true. Except, now that I was in London, I realized the stories might not have been big enough.

The buildings we drove past looked like a giant had been playing with blocks and got bored. Some of them were smashed sideways, and some of them were pancaked flat, and some of them were sliced down the middle – one half gone and the other half a dangling mass of broken beams and drooping floors and doors that went nowhere but the sky. There was glass everywhere being swept into piles by people in uniforms whose faces were pale with dust – and the air was full of dust too, and the clothes of the other people on the bus. I shifted my feet about, and they made dust patterns on the floor.

The bus stopped halfway down Oxford Street, and we all had to get out because there was an unexploded bomb in the road. I didn’t understand at first, and tried to keep on walking past shops with shattered windows and signs that said more open than usual, but then a man with a walrus moustache shouted, ‘Go away, little girl, unless you fancy being blown up!’

That was when I suddenly realized that it wasn’t a joke or a grown-up invention. There was a real bomb, and it might really explode. I felt my face flush, and I couldn’t work out whether I was excited or terrified, and whether I wanted to run a mile or sit down right there on the pavement.

Instead, I turned onto a side street and kept on walking towards Great Russell Street. It was warm now in the afternoon sun, and my cardigan itched me – English clothes always do – and my gas-mask case bumped against my hip. Barrage balloons glittered in the sun like fat silver moons, and I stepped over bits of fallen building and reminded myself that I was here to become a spy and put a stop to all this.

When I got to Great Russell Street, it was five minutes to four. I was just in time. I walked down the row of houses, counting, until I arrived at Number 13. It had a red-painted door with a brass knocker shaped like a fox, and standing in front of it was a boy. He had dark skin, a round body, and a round, friendly face surrounded by dusty, curly hair. He was wearing a dusty knitted pullover and shorts, and he had a dusty, cross-looking ginger cat with one white paw in his arms.

The boy and the cat both stared at me.

‘What are you looking at?’ I asked. ‘And what are you doing here?’

‘I solved the crossword,’ said the boy simply, as though that explained anything. ‘I suppose you did too?’

I narrowed my eyes at him, not wanting to admit that I had no idea what he was talking about.

‘The one in the paper,’ he went on. ‘The Junior Championship puzzle. The solution was a message, about training, and this address.’

I’ve learned since arriving in England that when someone tells you something, it’s always best to pretend you knew all along.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘The puzzle. I solved it too, and that’s why I’m here. I thought it was easy.’ The boy’s eyes lit up with respect, and I realized that was probably pushing it a bit. ‘Is that your cat?’

‘I found her,’ said the boy, petting the cat’s head gently. ‘In the rubble. I think she came from one of the houses that got hit last night.’

I don’t like cats. I think they’re too clever. But I liked how careful the boy was with the cat. It made me like him.

‘I’m May Lee,’ I said. ‘What’s your name?’

‘I’m Eric. Er, Eric Jones.’ The way he said that, with the pause, told me he was lying too. I respected that. ‘Do you think it matters that I’m not thirteen yet?’ he went on, frowning. ‘I’ll be eleven next month.’

‘I’ll be eleven soon too,’ I said, which was not technically a lie because I will, in half a year. ‘I shouldn’t think it matters at all.’

I still had absolutely no idea what we were talking about. How had the note I’d found in Hazel’s handbag ended up as the solution to a newspaper crossword? What other information had I missed?

‘I was almost late,’ I told Eric, just for something to say. ‘There was a bomb in the road.’

I was still a bit excited about it, and I wanted someone else to be too. But Eric just stood with the cat in his arms and stared at me as though I’d said something strange.

‘Where are you from?’ he asked. ‘You’re not from London, are you?’

I felt myself get all spiky with annoyance, because usually when English people ask where I’m from they’re being very rude. But then I looked at Eric’s curious expression, and something clicked into place. His accent wasn’t quite English. Mine isn’t quite yet, either, unless I concentrate, and I can tell when other people are trying as well.

‘I’m from Hong Kong, but I go to school in Deepdean,’ I said. ‘It’s in the country, over that way. You aren’t from London, either, are you? You’re—’

I struggled to think what the not-English bits of Eric’s voice sounded like. I couldn’t hold onto it at first, and then I had it. The newsreels.

‘You’re German !’

Suddenly my heart was beating as fast as it had when I’d realized about the bomb.

Eric had turned almost purple, staring round the street as though someone might pop out at any moment and arrest him.

‘Don’t SAY that!’ he hissed. ‘Please!’

‘But you are !’

‘I’m English !’ said Eric fiercely. ‘I am now, anyway. My family – we came here four years ago. Mama and Papa were musicians in Germany, famous ones. But my mama has dark skin, like me and my sister, and the Nazis hate people who look like us. They think we’re not really people at all. So we had to escape to England. We were supposed to be safe here. But then, about a month ago, Papa was taken away by the British government because he’s German. They think he might be a Nazi spy. I thought that if I could prove that we’re loyal, not dangerous, and if I could help end the war, then Papa – then they might let him come home.’

He gave a gasp, his face red and upset. Almost automatically, he reached for his right wrist, for a heavy, grown-up watch that was too big for him. I wanted to know more about Eric’s family, and Eric, but I was most interested in what he’d said about ending the war. My breath had caught as he said it.

‘I think this is something to do with the war too!’ I said. ‘That’s why I ran away—’

I stopped myself because I wasn’t supposed to be saying that, especially not to someone I’d only just met. We were always being warned about careless talk costing lives – and Eric was German, after all, even if he said he was loyal to Britain. But he looked excited.

‘I ran away too!’ he said. ‘I’ve never done anything like this before. My twin sister, Lottie, is the brave one, not me. But I’m good at puzzles. I even know Morse code! When I solved the crossword and saw what it said, I knew I couldn’t just let myself be evacuated, not with Papa taken. Our train left this morning, and I gave Lottie the slip on the platform. I put a note in her pocket to explain, and another letter for Mama for Lottie to post. It should stop Mama looking for me for a few weeks, anyway.’

I was very impressed.

‘Won’t Lottie tell on you?’ I asked.

‘We’re twins!’ said Eric. ‘She wouldn’t. Anyway, I’m usually the one not telling on her.’

As he was talking, the London clocks began to strike four. And then the red door we were standing outside opened.