- Home |

- Search Results |

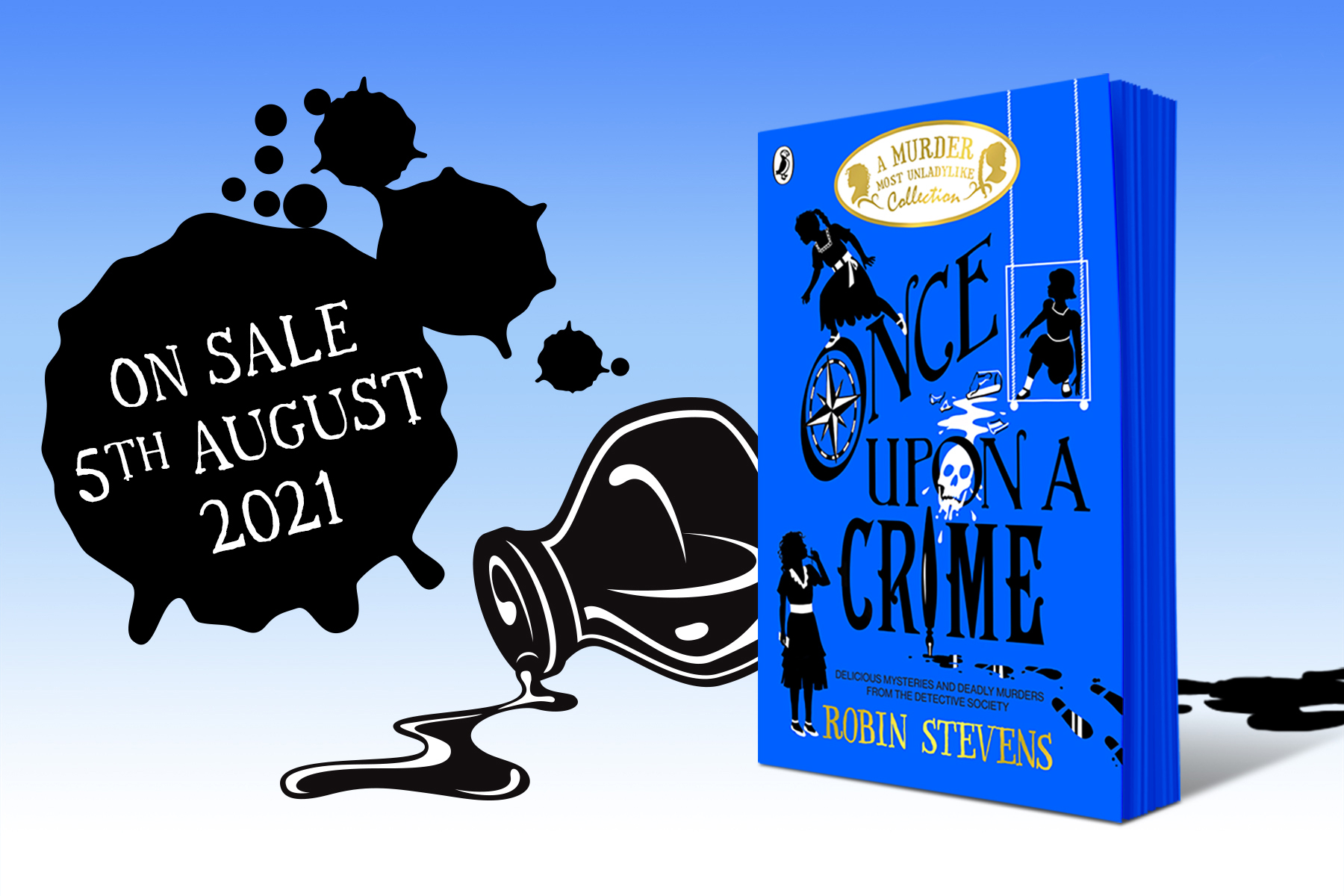

- Once Upon a Crime by Robin Stevens

Once Upon a Crime by Robin Stevens

Budding super sleuths will love the six new mini-mysteries in Robin Stevens' new book Once Upon a Crime. In this extract, Hazel Wong's little sister May is staying with her family in Daisy's uncle's flat for the summer. But when a mysterious murder occurs in the flat above, it's May's turn to play detective...

May Wong and The Deadly Flat

Written by May Wong, aged almost ten

Saturday 9th September 1939

I am May Wong and no one ever listens to me. If they had, I would still be in Hong Kong with my mother and Teddy instead of stuck in England with a war on, and I wouldn’t have to be speaking English and going to a stupid freezing-cold school with horrible European girls who stare at me. (I haven’t actually gone to Deepdean yet – my sister Rose and I are being put on the train tomorrow – but I know they’ll stare.)

Of course, Rose is excited about school. Rose loves books and she wants to please everyone. Which is why it was so unlucky that the day the murder happened she was the one playing on the stairs.

It’s sort of Rose’s fault that I’m here at all. I wasn’t supposed to be for two more years except that Rose was starting at Deepdean School (which is where Big Sister Hazel went, and her friend Daisy, and so where we have to go too). Father wanted to travel with Rose, and decided that I should come along with them so that I could practise my English and see that England is a nice place to be. Which it isn’t. We’ve been staying with Daisy’s uncle, Mr Mountfitchet, in his flat all summer. I was supposed to go home to Hong Kong with Father as soon as Rose went to Deepdean – but then war broke out, and everything went wrong.

I thought at first when we got to England that being at war would be an exciting adventure. There are sandbags in all the parks and air-raid warning signs on the walls of buildings. Father tried to distract me from seeing them, as though I was still a baby and not almost ten years old. (Well, nine years and four months, which is almost ten). Of course, I saw them, and so did Rose. She pretended not to because she’s trying so hard to keep everyone happy, but I don’t care about that.

We’ve all been fitted for gas masks that smell of rubber and squeeze my face like a hand, and people go by in the street with yards and yards of heavy black fabric sticking out of bags. And then last Sunday morning the grown-ups (which includes Big Sister Hazel now, and Daisy) all went into Mr Mountfitchet’s study and put the wireless on and played it very low so we wouldn’t hear.

I climbed up on top of the table in the dressing room next door and put my ear against the vent, so of course, I heard. First, the man on the radio did a long speech that I couldn’t really understand, saying that no one was safe but everyone had to be calm, and then Mrs Mountfitchet said in a very stiff voice, ‘So it’s war.’

Then there was a babble of voices, everyone talking at once, which resolved into –

‘You can’t risk the children on the journey home,’ said Mr Mountfitchet.

‘Rose will be all right at Deepdean, at least,’ said Big Sister.

‘But little May...’ said my father.

And that was when I was betrayed.

‘Should stay here with Rose,’ said Mr Mountfitchet. ‘Deepdean will accommodate. We can telephone them, but I can’t see any issues. It’ll be flooded with evacuees, anyway. If you feel you must go back—’

‘No question about it,’ said Father. I was sure he’d say that he needed me with him. But – ‘I have to go back to my family. If you’re sure the little ones will be safe?’

That’s why I hate Father now, and Mr Mountfitchet. I’m Father’s family, and so is Rose, and he shouldn’t be allowed to choose Teddy and my mother over us. (Hazel’s big enough to look after herself – and she’s going to university at Oxford next month, or at least she’s supposed to.)

I was so angry then that I ran away to our room and kicked the wall. I couldn’t even pretend to be surprised when Rose and I were called into the study and told the news hours later – but of course, no one bothered to notice that I wasn’t shocked.

So England is at war and I can’t go back home.

I’ve always wanted to fight, and do brave things, and be a hero, and at first I hoped that I would be able to help the grown-ups win this war so I could get on the ship home as quick as possible.

I put my head out through the blackout blinds that first night to see if I could spot enemy soldiers coming to kill us. I wanted to kill them first. But then Bridget, who’s the Mountfitchets’ maid, came in and found me. She got very upset that I was breaking blackout and told me to go to bed at once.

‘But the soldiers might be coming!’ I said. ‘I want to fight them!’

‘I’ll fight any soldiers who try to come in here; don’t you worry,’ said Bridget. I did believe her. Bridget isn’t the usual sort of maid, any more than the Mountfitchets are the usual sort of English people. I think, even though no one will say it in front of me, that they might be spies. But what I realized that night is that no matter how unusual Bridget and the Mountfitchets are, they won’t let me help them. No one lets children do anything brave – and especially no one lets me.

So this is why, even though I thought the war would be an adventure, it’s not. The only properly interesting thing to happen is the murder. And that’s why I’m writing all this down, so I have something to prove that there was a murder in the flat above this one, a murder that I solved. I’ve made at least one grown-up sorry for what they did, even if I can’t do anything to the ones I am really angry at.

Again, the grown-ups didn’t tell us that anyone was dead, they just whispered about it behind closed doors. I knew what had happened, though, because on Wednesday afternoon I heard the grocer talking about it with the maid from the third-floor flat. The grocer was on his rounds (in England, grocers are the people who deliver food every day – he comes just after 2pm, and I always go outside to play so I can listen to him gossiping with the maid), and the maid told him that Mr Murchison from the second-floor flat had been found dead in his bed that morning.

He was found by the charwoman who comes in a few times a week to clean for him. Mr and Mrs Mountfitchet live in the first-floor flat, and Mr Murchison lived in the one directly above. He was an old professor who went to the British Library to read every day. He was supposed to be very rich, only he didn’t look it when I saw him. That was all I knew about him.

Except that now I knew he was dead.

‘Couldn’t bear it,’ said the maid, and the grocer nodded. ‘Not another one, you know. It’s terribly hard. Poor man!’

‘Britain’s in a tight spot,’ said the grocer. ‘Invasion soon, I heard. Now, I’d better go, or I’ll be late.’

I realized what the grown-ups thought – that Mr Murchison was upset about the war, because he’d already had to fight in one years ago, and so he had... killed himself. Which was a stupid thing to think, but then again grown-ups are stupid, even the good ones.

And I was even more sure they were wrong when Rose had new nightmares on Wednesday night.

Rose has been worrying about the war all summer. Rose wants everyone to be safe. Her English is better than mine, so she’s been reading the papers. She told me all about Hitler rolling through Europe like a ball going down a hill, and all the awful things that happened while everyone got ready to fight him. There was an English submarine that sank in June with everyone still on board, and Rose couldn’t sleep for three nights because of it. I imagined all those people at the bottom of the sea, tapping and tapping to get out, and I told Rose so and she SCREAMED.

Rose has been even more worried since Sunday morning, now we know the war is an actual fact. But when she had bad dreams on Wednesday, I knew they weren’t the same as usual. Rose lay in her bed and cried and cried, and when she finally went to sleep I heard her say, ‘I’m sorry! I’m so sorry!’

I knew that Rose had nothing to be sorry for, because SHE didn’t cause the war and it isn’t OUR fault we’re in England during it (it’s Father’s), so I went over to her bed and put my arms round her and squeezed. She woke up with a jump and a shriek and I said, ‘Ling Ling, what’s wrong?’

‘Nothing,’ said Rose. ‘Go away.’

‘Won’t,’ I said. (We were speaking Cantonese, which is what we speak when Father can’t hear us. We’re supposed to be practising our English, but I don’t like it.) ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing,’ said Rose, and she began to cry again.

I poked her in the arm. ‘Tell me tell me tell me tell me,’ I said.

‘I can’t! It – it’s all MY FAULT!’ sobbed Rose, and then the whole story poured out of her.

It went like this.

On Tuesday at lunchtime, the Mountfitchets and Father were out, and Big Sister was supposed to take us to buy uniforms (mostly me, because I don’t have anything. I’d hoped that Deepdean would say no to me arriving two years early, but they didn’t. I’m going to be part of a new form for younger girls, and I hate it!). But Rose wouldn’t come, no matter how excited she was about Deepdean.

‘I won’t!’ she said. ‘There might be bombs!’

Big Sister Hazel explained again that there were no bombs – not yet, at least. I didn’t trust her about that, and nor did Rose, and we could tell Rose wouldn’t be swayed. So Big Sister said, ‘Well, I know your size, Ling Ling! I suppose you can stay here. You promise to be good?’

‘I promise,’ said Rose.

‘If I’d asked to stay, you wouldn’t have let me!’ I said as we walked down the street outside, me bumping into grown-ups and their gas masks with every step.

‘If you’d asked to stay, you’d have had some sort of plan,’ said Hazel. ‘Rose isn’t like that.’

This was rude but true. So to take revenge I asked her about the Mountfitchets being spies all the way to the department store, and she shushed me and blushed, and looked very suspicious. For someone who knows so many spies, she’s very bad at being sneaky.

So I had a boring afternoon fidgeting in fitting rooms (and then a less boring tea with Hazel and Daisy at the Ritz), but what was happening to Rose wasn’t boring at all.

After we had gone Rose sat on the stairs outside the Mountfitchets’ flat. The building they live in has four flats piled one on top of each other (they don’t even have a building to themselves! England is so strange!) with stairs in the lobby going up to each one, and a lift to get you there even faster. (Although Rose and I don’t take lifts if we can help it, because of the thing that happened to our brother Teddy in Hong Kong.)

Rose was playing with her paper dolls. She has a book full of brightly coloured outfits, and she spends hours cutting out little shirts and knickers and hats. It’s boring; Rose is boring. But what’s not boring is what she saw.

She hadn’t been there long when Mr Murchison went past her, off to the British Library, the way he always did. Rose says he looked the way he always did too: ordinary and dull in his tweed suit that was baggy at the elbows. She hardly looked up.

Until half an hour later, when the door to Mr Murchison’s flat opened again and a man came down the stairs. Rose knew that it was Mr Murchison’s flat he came out of (I asked her!) because his door squeaks, and she heard the squeak twice that day: once when Mr Murchison left, and then again. She was looking up when he came round the corner of the stairs and saw her.

She said he was tall (or was he just standing up, while she was sitting? She wasn’t sure), and European, with brown hair. He was wearing a nice new blue pinstriped suit with pink lining, but it was a bit creased and dusty, and there was dust on his brown shoes. He was wearing leather driving gloves. Rose really only cares about clothes, and you can tell that because it was all she could tell me. She thought he was younger than Mr Mountfitchet, but again she wasn’t sure. She hadn’t seen him go up into Mr Murchison’s flat, but she didn’t think much of that – Rose never does. She’s not suspicious like I am, and like Big Sister Hazel is. I want to be like Hazel when I’m older, a detective, and I will, just you wait and see. I’ve already helped her solve two cases.

He smiled at her and said, ‘Hello, young lady! Do you speak English?’

Rose nodded at him. She can get shy sometimes.

‘Well, I’ve just been into my father’s flat. I’ve left a surprise for him. But don’t tell anyone you saw me, all right? I’ll give you a shilling.’

Rose took the shilling, all pleased, and waved to him as he went on down the stairs. I remember us coming back, and seeing her looking pink and happy. Rose loves helping people, and she loves the thought of surprises. She didn’t say anything – but she waited to hear what Mr Murchison would say about his present.

And then the next morning, Mr Murchison was dead.

I remember Rose went pale when I told her. I remember that she hung about Bridget as she was cooking lunch, pestering her with questions.

‘Do you think he suffered?’ she asked. ‘How old was he? Will his son come to take his things away?’

‘Possibly,’ said Bridget, who is very honest. ‘Seventy, at least. And he doesn’t have a son or a daughter, so I should think his things will be sold along with his flat.’

And at that Rose turned as white as a sheet and ran away to her room.