- Home |

- Search Results |

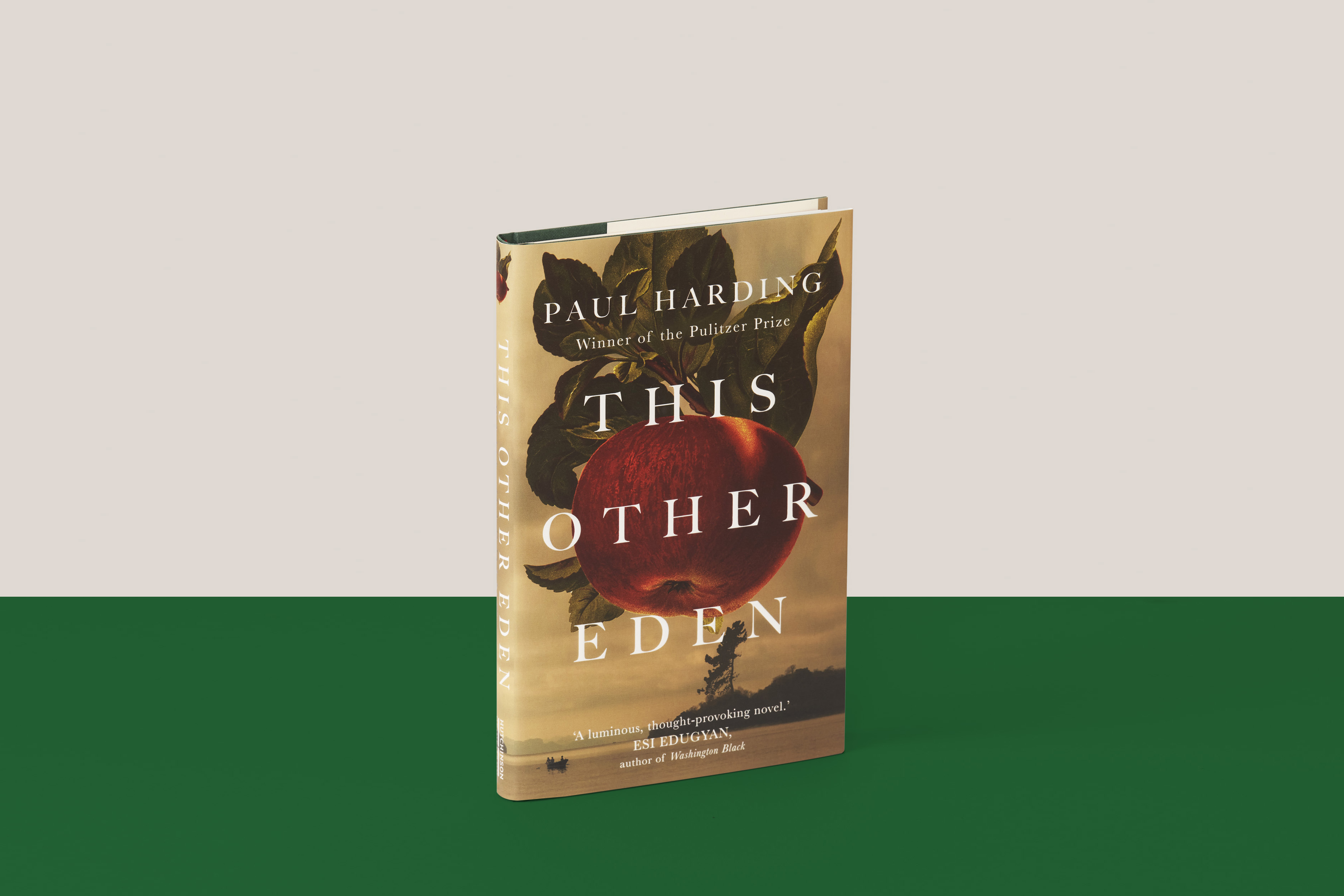

- Extract: This Other Eden by Paul Harding

Benjamin Honey—American, Bantu, Igbo—born enslaved—freed or fled at fifteen, only he ever knew—ship’s carpenter, aspiring orchardist, arrived on the island with his wife, Patience, née Raferty, Galway girl, in 1793. He brought his bag of tools—gifts from a grateful captain he had saved from drowning or plunder from a ship on which he had mutinied and murdered the captain, depending on who said—and a watertight wooden box containing twelve jute pouches. Each pouch held seeds for a different variety of apple. Honey collected the seeds during his years as a field-worker and later as a sailor. He remembered being in an orchard as a child, although not where or when, with his mother, or with a woman whose face over the years had become what he pictured as his mother’s, and he remembered the fragrance of the trees and their fruit. The memory became a vision of the garden to which he meant to return. No mystery, it was Eden. Years passed and he added seeds to his collection. He recited the names at night before he slept. Ashmead’s Kernel, Flower of Kent, Duchess of Oldenburg, and Warner’s King. Ballyfatten, Catshead.

After Benjamin and Patience Honey arrived on the island—hardly three hundred feet across a channel from the mainland, just under forty-two acres, twelve hundred feet across, east to west, and fifteen hundred feet long, north to south, uninhabited then, the only human trace an abandoned Penobscot shell berm—and after they had settled themselves, he planted his apple seeds.

Not a seed grew. Benjamin was so infuriated by his ignorance that over the next year he crossed to the mainland whenever he could spare some time and sought out orchards and their owners in the countryside beyond the village of six or seven houses, called Foxden, that stood directly across the channel from the island, and traded his carpentry skills for seeds and advice about how they grew and how to cultivate the trees and their fruit.

Benjamin and Patience and their sons and daughters and grandsons and granddaughters and great-grandchildren kept more and more to the island as time passed, but in the final years of the eighteenth century it was not as dangerous as it came to be later for Black man to range the land. Any able-bodied adult who kept peace and lent a hand surviving was accepted. So the story went among his descendants. So, Benjamin rambled around and found farms where he could help raise a barn or split shingles or clear an acre for crops and came home with seeds that quickened and struck roots and elaborated themselves into the shapes of his remembered paradise.

Roxbury Russets, Rhode Island Greenings, Woodpeckers, and Newtown Pippins. Benjamin Honey kept an orchard of thirty-two apple trees that began to bear fruit in the late summer of 1814, a decade after he planted them. Pippins were perfect for pies, Woodpeckers for cider. Children bit sour Greenings on dares and laughed at one another when their eyes watered and mouths puckered. Russets were best straight from the tree.

Benjamin Honey surveyed his orchard in the cooling air and sharpening, iridescent, ocean-bent sunset light, the greens and purples deepening from their radiant flat day-bright into catacombs of shadowed fruit and limb and leaf. It felt as if his mother were somewhere among the rows. She might step from behind a tree in a white Sunday dress that took up the shifting light and colors and smile at him. He inhaled the perfume, salted, as everything on the island, and took a bite of the apple he held.

On the first day of spring, 1911, Esther Honey, great-granddaughter of Benjamin and Patience, dozed in her rocking chair by the woodstove in her cabin on Apple Island. Snow poured from the sky. Wind scoured the island and smacked the windows like giant hands and kicked the door like a giant heel and banked the snow up the north side of the shack until it reached the roof. The island a granite pebble in the frigid Atlantic shallows, the clouds so low their bellies scraped on the tip of the Penobscot pine at the top of the bluff.

Esther drowsed with her granddaughter, Charlotte, in her lap, curled up against her spare body, wrapped in a pane of Hudson’s Bay wool from a blanket long ago cut into quarters and shared among her freezing ancestors and a century-old quilt stitched from tatters even older. The girl took little warmth from her rawboned grandmother and the old woman practically had no need for the heat her grandchild gave, no place, practically, to fit it, being so slight, and so long accustomed to the minimum warmth necessary for a body to keep living, but each was still comforted by the other.

The island a granite pebble in the frigid Atlantic shallows, the clouds so low their bellies scraped on the tip of the Penobscot pine

Esther’s son, Eha—Charlotte’s father—rose from his stool and one at a time tossed four of the last dozen wooden shingles onto the embers in the stove. The relief society inexplicably had sent a pallet of the shingles to the settlement last summer. There was no need for them. Eha and Zachary Hand to God Proverbs were excellent carpenters and could make far finer cedar shingles than these. But as with each of the past four years, summer brought food and goods from the relief society, and some of the supplies were puzzling to the Apple Islanders, like the shingles, or a horse saddle, once, for an island that only had a handful of humans and three dogs on it. With the food and stock also came Matthew Diamond, a single, retired schoolteacher who under the sponsorship of the Enon College of Theology and Mission traveled from somewhere in Massachusetts each June to stay in his summer home—visible on the mainland in clear weather 300 yards across the channel, in the village of Foxden— and row his boat to Apple Island each morning, where he preached, helped with a kitchen garden here, a leaky roof there, and taught lessons in the one-room schoolhouse he and Eha Honey and Zachary Hand to God Proverbs had built.

Useless spalt anyway, Eha said, closing the woodstove on the last of the shingles.

Tabitha Honey, Eha’s other daughter, ten years old, two years older than her sister Charlotte, scooted on her behind across the cold floor to get closer to the stove. She wore two pairs of stockings, three old dresses, a donated wool coat the society had sent, and the one pair of shoes she owned, boy’s boots passed down from her big brother, Ethan, when he’d outgrown them. They were too big for her and she’d stuffed the toes and heels with dry grass that poked out of the split soles like whiskers. Tabitha wore another square of the Hudson’s Bay blanket wrapped over her head and shoulders.

C’mere, Victor, Tabitha said to the cat curled behind the stove. Tch, tch, c’mere, Vic. She wanted the cat for her lap, for some warmth. Victor raised his head and looked at the girl. He lowered his head back down and half-closed his eyes.

I hope you catch fire, you no-good hunks, Tabitha said.

Ethan Honey, fifteen, Eha’s oldest child, sat on a wooden crate across the room, in the coldest corner, drawing his grandmother and little sister with a lump of charcoal on an old copy of the local newspaper that Matthew Diamond had given him last fall the day before he closed up his summer house and returned to Massachusetts. The boy’s nose was red, his lips purple. His fingers and hands were mottled white and blue, as if the blood were wicking into clots of frost under their skin. He concentrated on his grandmother and sister and their entwined figures came into finer and finer view across the front page of the Foxden Journal, seeming to hover above the articles about the tenth annual drill and ball, six Chinamen deported, a missing three-masted schooner, ads for fig syrups, foundries, soft hats, and black dress goods.

Victor raised his head and looked at the girl. He lowered his head back down and half-closed his eyes

Tell us about the flood, Grammy, Tabitha said, still eyeing the cat.

Charlotte lifted her head from her grandmother’s breast and said, Yes, tell us again, Gram!

Ethan looked from his drawing to his grandmother and sister and back. He said nothing but wanted as much as his sisters for his grand- mother to tell the story about the hurricane that had nearly sunk the island and had nearly swept away his whole family.

Eha went from the stove to the corner opposite where Ethan drew and tipped a basket sitting on a shelf toward him and looked into it.

I’ll fix these potatoes and there’s a little salt fish left, he said. A can of milk, too.

You want to hear about the flood? That old flood? Again? Esther Honey said.

Yes, Gram, please!

Please, Gram, tell us!

Well, that old flood was almost a hundred years ago, now, she began.

Way back in 1815.