- Home |

- Search Results |

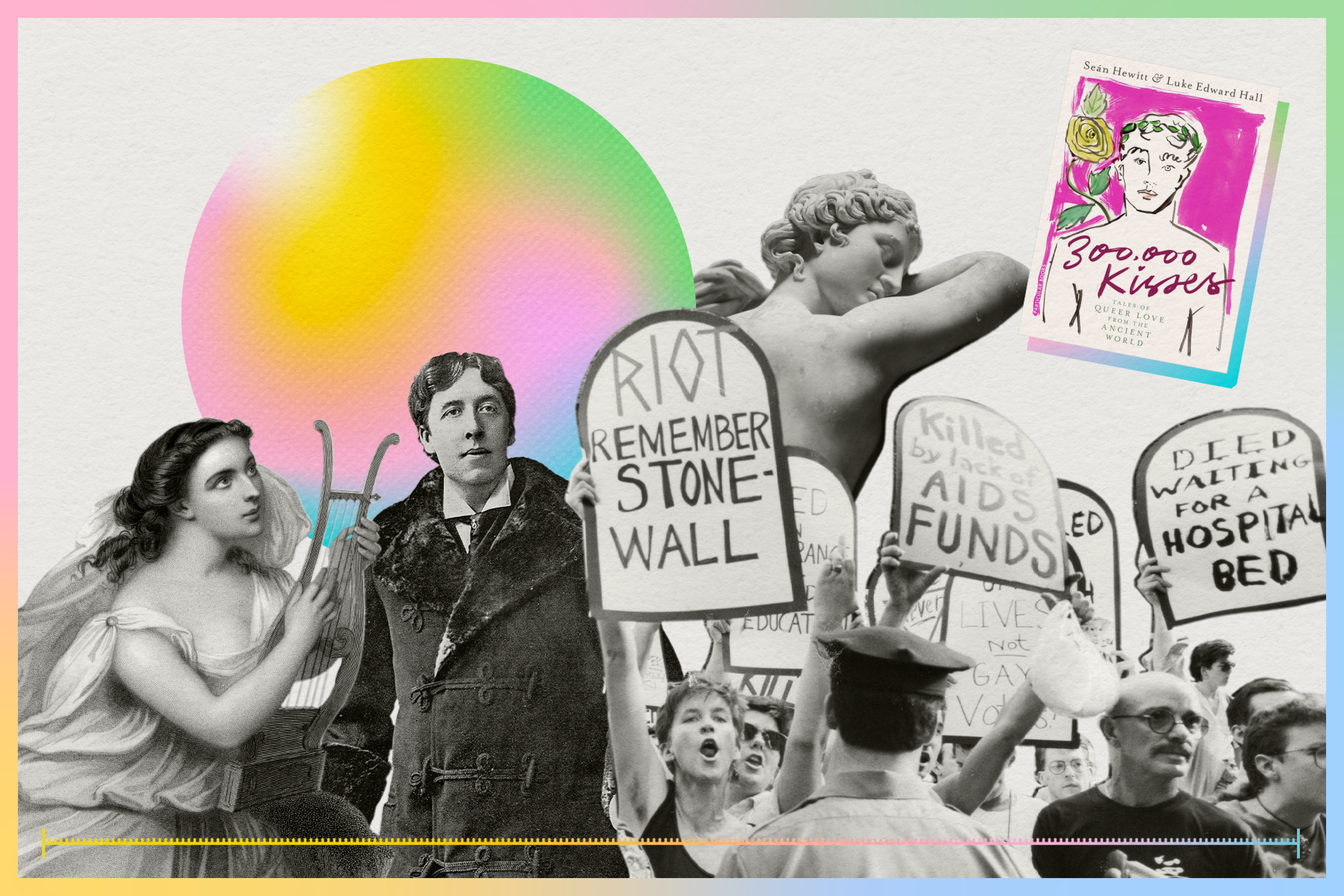

- From Sappho to Stonewall, and beyond: how fiction tells LGBTQ+ history

Fiction tells us so much about the time we live in – and LGBTQ+ writers have been writing since the early days of literature. Their stories have often, but not always, been marginalised, but they have always said something about the era in which they were first told or published. Here, we take a look at the evolution of queer fiction across the ages – for brevity’s sake, focusing on the Western world – and what it reflects about that moment in history, from Sappho, to Stonewall, and beyond.

Queer stories in antiquity

Madeline Miller’s 2011 hit The Song of Achilles is a moving queer retelling of The Iliad from the perspective of young prince Patroclus that simultaneously reflects pride in same-sex relationships (Achilles remains adamant throughout that he and Patroclus be seen together) and modern anxieties about romantic relationships and masculinity – how men can be gentle, how to manage family expectations.

But being queer wasn’t always coded as different, and many myths don’t require retelling: even before the printed word, ancient mythology and religious narratives were rife with romantic and sexual engagements between people of the same gender.

Patroclus and Achilles were already cast as lovers in Aeschylus’s 5th Century tragedy The Myrmidons which, in its time, reflected the widespread tradition of pederasty – a romantic, typically sexual, relationship between an older man and a younger boy – that, while troubling when seen through today’s moral lens, was a tradition that defined contemporary Greek life and provided a cultural model that “fostered cohesion” in city society, according to scholar Doyne Dawson’s Cities of the Gods. Plato’s Symposium, from roughly 385–370 BC, cites Aeschylus’s depiction of the two as a celebratory example of love’s power to elicit sacrifice and bravery. Homosexual romance, in Greek culture, was worthy of veneration.

Greek society’s view of gender was patriarchal but fluid; Hermaphrodituswas depicted with male genitalia but female breasts and thighs

Though the word “transgender” had yet to exist, gender mutability was pervasive in the world of Greek mythology, too. A person’s sex was often changed at will by the gods: in one myth, Artemis changes a shepherd from a man to a woman after he glimpses the goddess bathing in the nude; in another, the prophet Tiresias was changed into a woman for seven years for displeasing Hera.

That the gods behaved in this way – and that being changed from a man to a woman was seen as punishment – reflected Greek society’s view of gender, which was patriarchal but fluid; indeed, Hermaphroditus, the child of Hermes and Aphrodite (and, you guessed it, the origin of the term “hermaphrodite”), was often depicted, and beautifully it must be said, with male genitalia but female breasts and thighs.

The Greeks’ acceptance and, indeed, celebration of male-male relationships continued into ancient Rome. Like “transgender”, terms like “heterosexual” and “homosexual” did not yet exist; in Rome, sexual interactions between men were normal. Accordingly, Virgil’s Eclogues (1st Century BC) includes a male shepherd who proclaims his love for a younger man, while The Satyricon (1st Century AD) features a similar relationship between its narrator Encolpius and his young companion Giton. Some of Catullus’s poetry, meanwhile, contains specific references to anal and oral sex between men.

There is mounting evidence of further LGBTQ+ stories from history; new books like 300,000 Kisses: Tales of Queer Love from the Ancient World, in which authors Luke Edward Hall and Seán Hewitt unearth scads of evidence of queer love in antiquity, are being published with increasing regularity.

While many queer stories were lost to history, many more were wiped out by heteronormative scholarship of the last few centuries

But while many queer stories of this time were lost to history, many more have been wiped out by heteronormative scholarship of the last few centuries. The sexuality of ancient Greek poet Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BC) – whose name provides the etymological basis for the word sapphic and whose birthplace, the island of Lesbos, does the same for lesbian – remains hotly debated by scholars. However, many 20th-century scholars have since made the case that a mistranslation by one of her early translators in the 18th Century, which characterised a lover in a poem as male, led to her heterosexualisation for the following two centuries.

The Middle Ages

Even stories from the medieval period, often presumed as an era of social and political stagnation and regression, are now seen to have contained references to queer relationships. A story of a lesbian relationship from 12th Century Ireland, in which a woman admits to King Niall Frosach that she has had an encounter with another woman, has resounded through literature since – most recently in a poem called “Labhram ar Iongnaibh Éireann”, whose 1938 translation cut the story, meaning it was lost until a new translation by Damian McManus in 2008.

Scholars believe that attitudes towards same-sex relationships fluctuated during the period. The vaunted works of Shakespeare contained numerous references to homosexuality, most explicitly in Sonnets 18 and 20, which are love poems directed towards men.

Paulinus of Nola, a bishop in Rome in the 4th and 5th Century, wrote passionate love poetry to writer Ausonius, but records show that he distanced himself from Ausonius later in life, perhaps in response to persecution and changes in social mores.

Renaissance

Social attitudes toward queerness in the Renaissance borrow heavily from antiquity and the Middle Ages. In Italy, at the centre of the movement, homosexuality was accepted by some and debated by others; in the Church it was frowned upon because it denied procreation, but art from the time suggests that male-male relationships remained fairly commonplace, even celebrated.

Giovanni Boccaccio’s landmark work of humanism, The Decameron (14th Century), once contained a litany of gay innuendo, but it was omitted, on purpose, by English translators in the 17th and 18th Centuries. One even admitted that he found the text “so licentious in many places, that it requires some management to preserve his wit and humour, and render him tolerably decent […] It may still be thought by some people, that I have rather omitted too little, than too much.”

Near the end of this period, as the Age of Enlightenment loomed, an Italian priest named Antonio Rocco anonymously published a dialogue titled Alcibiades the Schoolboy, in defence of anal sex between men. Sometimes referred to as the first homosexual novel, it is modelled on the Socratic dialogue style, and finds a teacher citing Nature, Ancient Greece, and counterarguments about Sodom and Gomorrah in support of his argument.

Enlightenment and 19th Century

As the Age of Enlightenment gave rise to widespread debate about human nature and reason, so too did it firm up church dictums into state-run legal systems; so while queer behaviour and society became much more visible in this era, it also became more distinctly punishable by law, as acts like the 1533 Buggery Act – at the time less applicable to homosexuality and applied more liberally to sexual acts unrelated to procreation – transformed subtly into anti-gay law.

Accordingly, publishing literature with gay themes became increasingly dangerous, leading to a rise in more covert, coded queer literature. References to Greek and Roman mythological characters became commonplace as gay signifiers in novels that straight readers would overlook, while in new genres like Gothic and horror fiction, homoerotic and lesbian subtext often rose to the fore: Matthew Lewis’s Gothic masterpiece The Monk (1796) features an intense connection between the title character and a fellow monk named Rosario; when Rosario is revealed to be a woman named Matilda, they consummate their relationship, but the queer context remains unshakable.

Writers in the 19th Century became emboldened by these forebears: Emile Zola published Nana, which featured lesbian scenes and a gay character named Labordette, in 1880; Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu published the first lesbian vampire story – a genre that today looms large in the queer canon – with Carmilla in 1872, and Oscar Wilde shocked audiences with his depiction of a gay hedonist in The Picture of Dorian Gray in 1890. That Wilde was imprisoned from 1895 to 1897 was a product of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which made even private homosexual acts – say, sending a letter of affection – an offence.

20th Century

The 20th Century saw perhaps the biggest fluctuation of LGBTQ+ rights – countries often criminalised or decriminalised queerness depending on government, economic situation, or moral panic (though all three tended to go hand-in-hand) – but queer literature proliferated nonetheless.

The tone of these literary works tells us the milieu out of which they sprung

In France, where same-sex relations had been decriminalised since the French Revolution, Marcel Proust published À la recherche du temps perdu (1913), which openly discussed homosexuality. Before that, Nobel Prize-winning French author André Gide published his 1902 semi-autobiographical novel The Immoralist, and even E.M. Forster – despite living in England, where he was forced to conceal his homosexuality – was busy in 1913 and 1914 writing Maurice, a bildungsroman in which a man comes to grips with his sexuality through relationships with other men, even against the backdrop of a hostile world. (Forster’s struggle is captured in gorgeous new history book Nothing Ever Just Disappears by Diarmuid Hester (2023), which traces the unknown histories of seven important queer figures in literary history.)

The tone of these works – freewheeling and irreverent in Gide; deep-thinking but casual in Proust; and affirmative in Forster – tells us the milieu out of which these works sprung. In France, there was a laissez-faire attitude toward same-sex relationships; in England, gay people – including authors – were, at least in secret, pushing to self-define against the world’s unsavoury, even criminal definition of them. That Maurice went unpublished until the 1970s speaks volumes, too.

There were other major works in the early-to-mid-20th Century featuring queer relationships and characters – Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), often considered an early transgender novel for the way its protagonist changes gender; Carson McCullers’ Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941); Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948); Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (1952), originally published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan because of its lesbian content; James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956); Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckenridge (1968).

Late 20th Century authors were writing explicitly about the politicised experience of living as a queer person

But as queerness became better-defined, it became easier to see, and to suppress. As gay bars proliferated as spaces to share queer culture, they became increasingly targeted by police. On 28 June, 1969, in the most famous queer uprising in history, the patrons of the Stonewall Inn in New York City fought back against a police raid; the protest spread and within weeks, activists were organising and marching, establishing new pathways for communication and empowerment – newspapers in support of gay men and lesbians – and a new, increasingly politicised take on literature.

Suddenly, more explicitly gay novels were being published all the time: significant works by Edmund White, Alan Hollinghurst, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Armistead Maupin, and hundreds of others were writing explicitly about the politicised experience of living as a queer person, or at the intersection of queerness and other marginalised communities.

21st Century

The fight for equality imbued queer literature with new fervour, but even as LGBTQ+ rights spread, there emerged new realms to explore. With the proliferation of legal same-sex marriage across the Western world in the 2000s and 2010s came a host of new kinds of queer fiction: easy-going gay rom-coms (like What If It’s Us) and queer YA fiction (She Drives Me Crazy), which often enough overlaps, as in Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue.

Of course, the fight is far from over; transgender people still suffer inordinately and remain targets for hatred and bigotry in society. Books like Shon Faye’s powerful “argument for justice”, The Transgender Issue (2022) is a rallying cry for trans understanding, celebration, and liberation. Meanwhile, fiction by trans authors, like Torrey Peters’ incredible novel Detransition, Baby (2021), continue to create understanding and empathy – as fiction so often does.