- Home |

- Search Results |

- The vital freedom of reading LGBTQ+ books

One of my favourite things to do is visit bookshops. Whenever I’m having an off day, I’ll head into the heart of London where I live and make my pilgrimage: starting at iconic Gay’s The Word, I walk down through Bloomsbury, stopping at shops on Gower Street, Charing Cross Road and Piccadilly before making my way home.

It’s a ritual that I’ve been following since my teenage years. Back then, I was freshly out of the closet and still a little trepidatious about displaying my queerness in any overt way. In one large bookshop, I would surreptitiously make my way to their then-small LGBT section, avoiding eye contact with the (usually older) men who also lurked in that corner of the shop.

It was there that my eyes were caught by the brilliant blue cover of a YA novel by David Levithan, Boy Meets Boy. For weeks I thought about it until one day, a compulsion gripped me and I bought the book. Scared of reading it at home, I went to a nearby café and read the whole thing in one sitting.

I find it hard now to recall the minutiae of the plot, although I do remember that Levithan’s novel was something of an outlier at the time. Published in 2003, it was about the relationship between two teen boys and took place in a world that was gloriously accepting of LGBTQ+ people. Aside from one character who struggles with his homophobic parents, the small American town and stereotypical high school of the novel presented an almost utopic vision of queer life, one where almost everyone was gay-friendly. Moreover, the novel’s ending was one filled with hope and happiness. At the time, to me, it felt revolutionary.

Reading Boy Meets Boy was the first time that I read a novel in which I felt represented on page; it offered up a vision of what my life could be. I was aware that the novel presented something of a fantasy, not only because of its overwhelmingly positive portrayal of gay adolescence, but on account of its romanticised notion of teen relationships, which was as sweet as the three Love Hearts sweets emblazoned on the cover.

It was the first time that I read a novel in which I felt represented on page and it offered up a vision of what my life could be

Nevertheless, for a gay teenager like myself, the novel provided some semblance of solace during a time I often felt isolated and alone in my experience as a young queer person. It also kick-started a life-long love affair with queer literature in all its guises, one in which I would discover books that would shape who I am today.

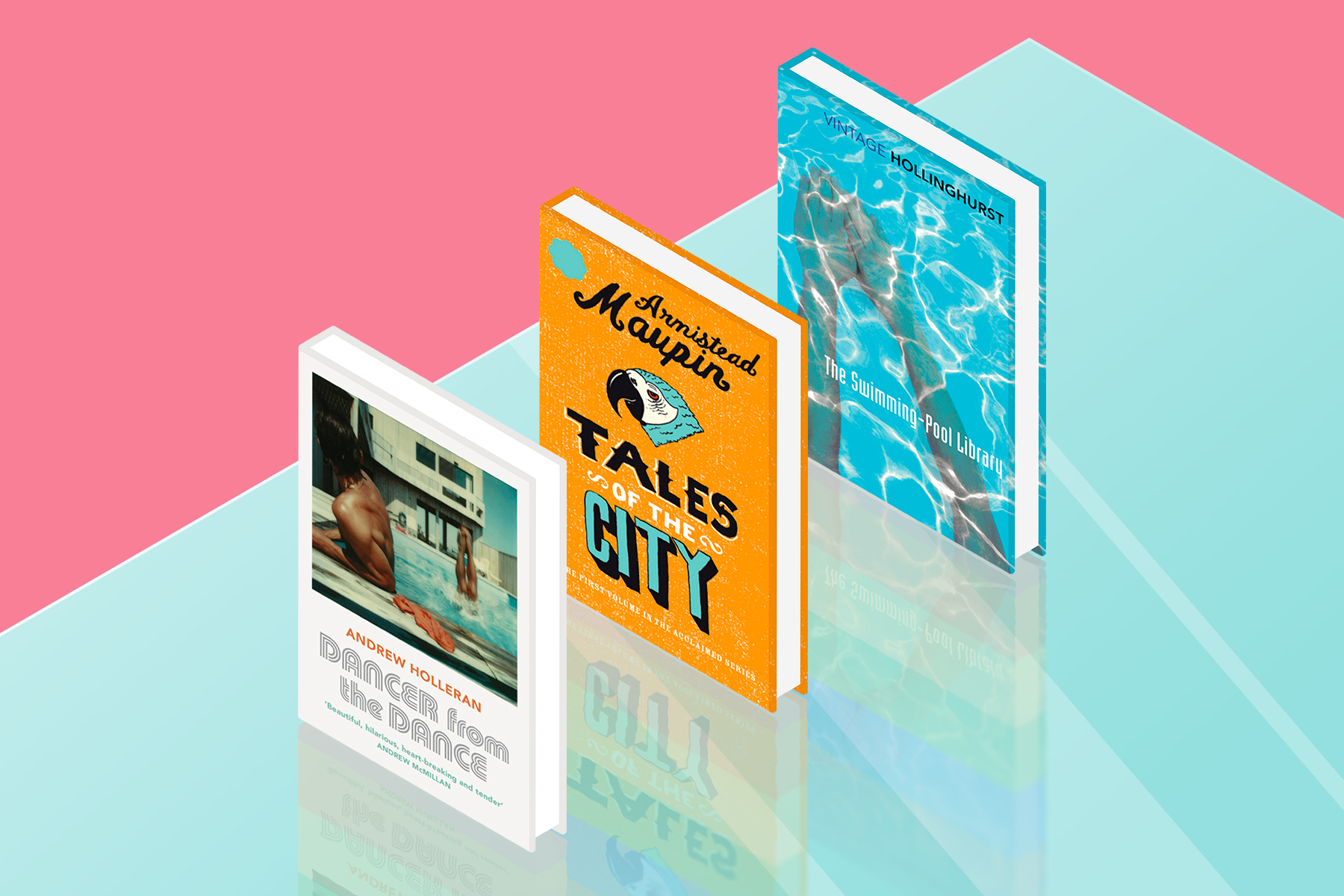

I’ve written before about the impact that Armistead Maupin’s decade-spanning Tales of the City saga had on me as an 18-year-old transplanted into a strange city. But there are also other novels that I feel an intense connection to.

Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Hours is one book that I revisit almost every year. I admit that I saw the movie first, but once I dived into the novel, I found myself transported by his prose and the interconnected lives of the characters. It was also the first time that I was confronted with the reality of HIV/AIDS, outside of fear-mongering media narratives and playground homophobia.

That led me to the work of Alan Hollinghurst. I read his Booker-winning novel The Line of Beauty in my late-teens, picking up a hardback copy of the novel from a second-hand book shop in Brighton while I was at university. Hollinghurst’s depiction of the doomed era of Thatcherite excess and the friction between the HIV/AIDS crisis and political antipathy taught me about a period of British history that had previously felt so distant from my own life but which I now saw as horrifyingly recent.

Books to change your life

I read Hollinghurst’s earlier, debut novel, The Swimming-Pool Library, a few years later. Set just before the height of the AIDS crisis, in decades following the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, it presented a gay life as a sort of modern bacchanalia where around every corner was an opportunity for erotic escapades. But The Swimming Pool Library was also caught up in undercurrents of conflict surrounding class, race and an arrogant ambivalence for the past – in this case the implications of living life as a queer person when it was still illegal. Hollinghurst’s novel provided a snapshot from a period of queer history that often feels overlooked, a time where LGBTQ+ lives were tentatively stepping outside of the shadows. I was, naturally, hungry for more.

It was fluke that led me to satisfy that itch. On one of my pilgrimages through London’s bookshops, I came across an imported copy of Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance.

Published in 1978, Dancer from the Dance is a funny, celebratory, unflinching and razor-sharp snapshot of gay life in 1970s New York. Like The Swimming Pool Library, the novel is set just before the devastation wrought by the HIV/AIDS crisis in the years following the 1969 Stonewall uprising, often cited as the birthplace of gay liberation.

Often compared to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Dancer from the Dance follows the lives of gay men as they search for love, lust and liberation in the discotheques of New York and beaches of Fire Island. Told initially through gloriously biting and fabulous letters between two men, one of whom has left the city and relocated to the South, and the other who remains in New York, the story morphs into a novel-within-a-novel. That story focuses on the friendship between Malone, the golden boy of the New York gay scene, and Sutherland, a campy and acerbic queen with a penchant for drugs, sex and socialising as if it were an extreme sport.

The novel ends under the spectre of death, a conclusion that by today’s expectations for queer storytelling might be considered deeply problematic. But Dancer from the Dance is very much a product of its time: along with repeatedly burying its gays, the novel’s approach to class, race and misery feel out-of-step in an era of queer optimism. And yet, as the poet Andrew McMillan argued in his review of the novel in 2019, there is something timeless in the hedonistic swirl of gay New York that Holleran so astutely documents.

Re-reading this novel at a time when many of my friends were getting married or having children resonated with my own sense of unease about the trajectory of my life

Take, for example, the way the novel’s narrator describes LGBTQ+ friendship: “Of all the bonds between homosexual friends, none was greater than that between homosexual friends, none was greater than that between the friends who danced together. The friend you danced with, when you had no lover, was the most important person in your life.”

Holleran even captures the segmented nature of the queer community, with one of the letter writers admitting that the story being told documented only “a tiny fraction of the mass of homosexuals” living in New York during that time.

The stereotyping and racial fetishization in the novel are another teeth-clenching sign of the times the book was written in, although as McMillan noted in his review of the book, Dancer from the Dance is not a hagiography. (McMillan also, quite rightly, draws comparisons between this and the racist behaviour on dating apps today.) But unlike the YA novel I read as a teenager, Dancer isn’t portraying a utopic vision of community.

In fact, underpinning the novel is a sense of confusion and existential worry about what, exactly, gay life is in an era where liberation seems possible. Unshackled from heteronormativity and caught up in the swell of early gay liberation, the concerns of the American Dream begin to shatter. “We are free to do anything, live anywhere, it doesn’t matter,” Malone says to Sutherland. “We’re completely free and that’s the horror.”

I had stories like Boy Meets Boy, which offered me an alternative narrative where queer lives were filled with possibility and a chance for happiness

Re-reading this novel at a time when many of my friends were getting married or having children resonated with my own sense of unease about the trajectory of my life. As LGBTQ+ lives become more mainstream and acceptance grows, we find ourselves once again navigating how we fit into society.

However, unlike Malone, who suffers through shame and an almost antagonistic relationship with his queerness, my own relationship with my identity feels more solid; I had stories like Boy Meets Boy, which offered me an alternative narrative where queer lives were filled with possibility and a chance for happiness.

I’ve since read another of Holleran’s novels, Nights in Aruba, which follows the character of Paul as he navigates his life as a gay man in New York, middle age and concealing his homosexuality from his mother, who he finds himself living with. It again struck a note with me – not just because I’m quickly approaching middle age but because I, too, have found myself back living with my mother.

What I’m certain about is that in the not-too-distant future there will be another queer novel that will either help me see my queerness in a new way, teach me about other LGBTQ+ experiences or help me move through the events of my own life with the knowledge that I’m not alone. In fact, perhaps it’s time for another pilgrimage.