- Home |

- Search Results |

- How Art Spiegelman made comics what they are today

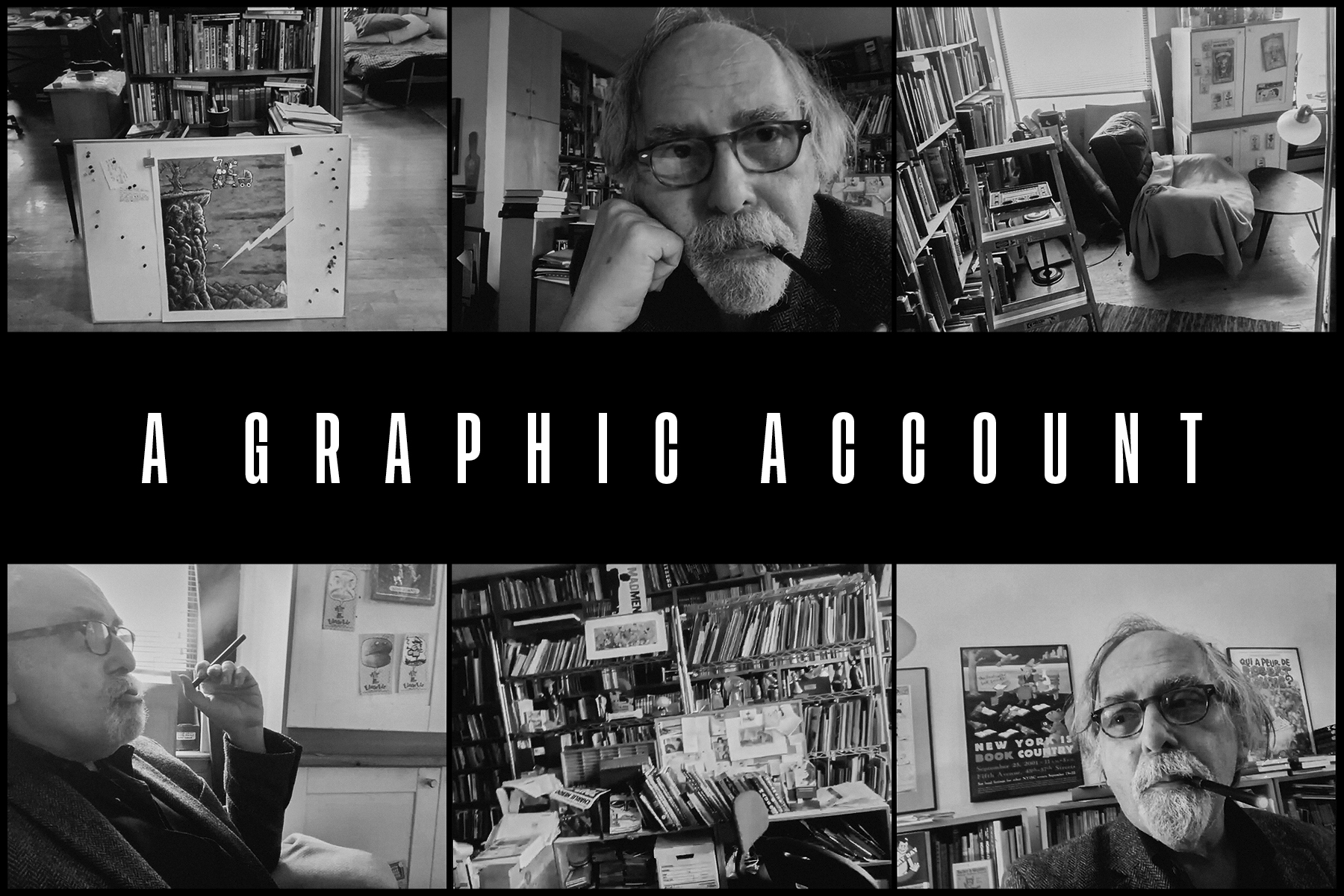

How Art Spiegelman made comics what they are today

If you’ve ever enjoyed a graphic novel, you probably have the Maus author and RAW magazine founder to thank. Here, Spiegelman discusses the pandemic and looks back on his revolutionary career arc, from MAD magazine to the modern day.

Art Spiegelman isn’t taking the pandemic personally.

Which is to say it may not inspire a graphic novel from him, even though he once stated, in the intro to In the Shadow of No Towers, that “disaster is my muse”. That book was based on the events of September 11, 2001, in New York City; his most famous work – Maus, a two-part work that earned Spiegelman the first Pulitzer prize for a graphic novel in 1992 – was based on the Holocaust.

“Disaster,” the 72-year-old emphasizes over Zoom, exhaling a plume of vape smoke, “is still my muse. But catastrophe, no.” And while he wonders if “after the pandemic maybe I’ll have something to say about it”, these days, the grandfather of comics isn’t much looking to write another graphic novel.

Fair enough: if anyone could be said to have done more than a lifetime’s work to establish an artform, it’s Spiegelman. The author both of comics’ most revered masterpiece (Maus) and the co-founder of a literary comics magazine that launched some of the medium’s most critically acclaimed names, it’s arguable that nobody has had a stronger and wider influence on the public perception of comics than Spiegelman.

Developing his style…

For a preteen Art Spiegelman in the early 1960s, the world of comics was small enough – “a shtetl”, he calls it now – that, as a result, “I could tell you who inked which issues of things that Jack Kirby published, even though I didn’t like Jack Kirby that much!”

But his career really started, he says, “with a fascination with MAD magazine”, the satirical American humour magazine whose subversive comics and writing inspired a generation of humourists. “You may or may not have seen in [Spiegelman’s collection of early career work] Breakdowns there’s a strip called ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!’ and there’s one part about seeing MAD that changed my life. It was like a codex to the adult world, and basically carried that message of ‘the whole adult world is lying to you and we here at MAD are sort of adults.’”

'I just figured we should show the world what should and could exist [in comics] at a moment they were in decline.'

That subversiveness was informing a movement. Robert Crumb had founded Zap Comix, where he and a cadre of fellow cartoonists were chronicling the changing world and creating comics that plumbed the complexities of adult life: sex and relationships, religion, and drugs, mostly.

…then platforming others

In 1977, Spiegelman met his would-be wife Françoise Mouly, an architecture student in the midst of moving to publishing. Mouly, now the art editor of The New Yorker, urged Spiegelman to co-found a literary comics magazine to spotlight the comics talent they were seeing around them. Spiegelman had done this before, in the early 70s, with a magazine titled Arcade – “It was a thankless task,” he says now; “I was not unhappy when Arcade folded” – and while he swore he’d never found a comics magazine again, Mouly convinced him.

RAW, a celebration of graphic literature as art, was intended to shift perceptions of comics, and quickly became a haven for a new wave of comics artists influenced by underground comics. It also reprinted newspaper strips from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries worthy, in Spiegelman and Mouly’s eyes, of renewed artistic appreciation.

“I wanted to just show what could be done in a better world, because I had tried to convince Playboy, who I’d been working for, and High Times, to do comics but not have them be about sex or drugs – to give them the same license that they gave to their other pieces. Playboy was publishing Nabokov and eventually Philip Roth and whoever, without insisting that they have sexual content in the stories especially. I wanted that for cartoonists, but it wasn’t coming. So, I just figured we should do this to show the world what should and could exist at a moment when underground comix were in decline.”

‘Graphic novels’ and the year that changed comics

In 1972, Spiegelman published a three-page comics strip in which he told a short story about his father Vladek’s experience of the Holocaust (with Nazis as cats and Jews as mice), simply titled ‘Maus’. Research for it required trips to New York City to interview his father, but Spiegelman continued to visit long afterward, too. Their relationship, long a tense one, eased when Spiegelman interviewed him: “I found a safe harbour with my father when we were talking about the death camps. It was something he didn’t have to ask for my attention. And he liked having me there.”

The strip, says Spiegelman looking back, “was a turning point for me. I had a lot more to tell than those three pages. And that offered the possibility of making a long comic book, one that needed a bookmark.” Spiegelman spent the latter half of the 70s and early 80s interviewing his father, and writing and serialising in RAW.

“I had already started working on Maus when RAW started, so I had to figure out how to do both, and that meant taking Maus into a serialised form in RAW magazine. That’s how a new issue was catalysed…when a chapter of Maus was completed.”

'I found a safe harbour with my father when we were talking about the death camps. It was something he didn’t have to ask for my attention.'

Following a rave review of the ‘Maus’ serials in the New York Times, the first six chapters were published, in 1986, in a single volume titled Maus: A Survivor’s Tale and subtitled My Father Bleeds History. The book forever changed the perception of comics.

“1986 was a banner year for newspapers wanting to write about comics, graphic novels, whatever they were,” says Spiegelman. “But they almost all had the same headline, which was ‘POW, BAM, ZAP, comics aren’t just for kids anymore!’ And that was because the same year as the first volume of Maus came out, Watchmen came out and The Dark Knight Returns came out. So, from its inception, it had its superhero genre thing and then I was sort of like, out of that group of three, coming from somewhere else. There was room for all of these genres. And that was like a landmark.”

‘Not just for kids anymore’: Pulitzers, prizes and today

Spiegelman continued work on Maus, serialising the rest of the story in RAW until 1991, when he published the book’s second volume, subtitled And Here My Troubles Began. Now a complete two-volume work, the graphic novel won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

“At the time,” says Spiegelman now, laughing, “I thought it was a hoax!”

His Pulitzer win earned Spiegelman’s work – and comics as a whole – unprecedented attention and acceptance from academia, and fundamentally changed the public’s view of comics. His work in Arcade and RAW had fostered a young generation of talent, and Maus had created interest in their work.