- Home |

- Search Results |

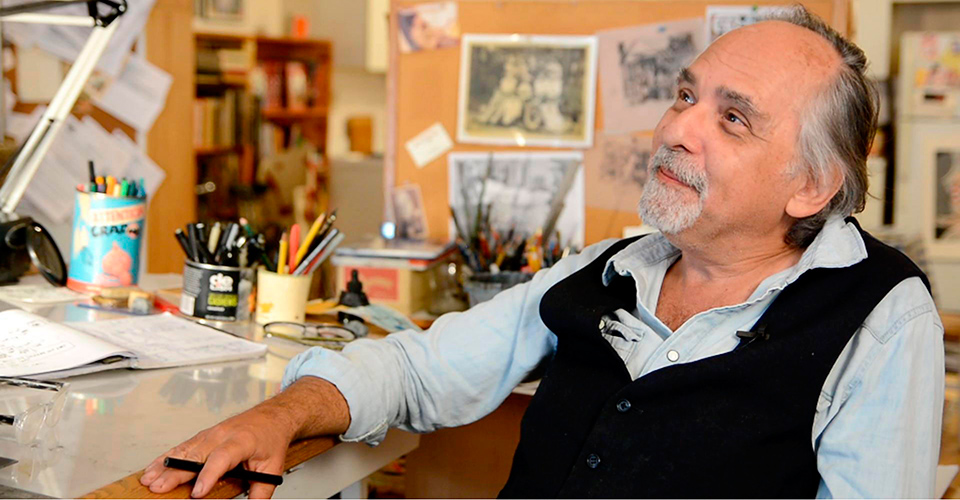

- ‘I’ll always have a 500-pound mouse chasing me around’

“Better to turn seventy than not, I guess,” is Art Spiegelman’s initial reaction to his milestone birthday. But, as with most of what he says, this statement is delivered with a distinct tone of affable sarcasm as he reflects on his own triumphs, troubles, and one rather famous mouse.

Spiegelman’s life has always been about comics. He says he realised he wanted to create them himself “as soon as I figured out they were made by people”, and the magazine that had the most profound impact on him was Mad. “It invented a certain approach to irony and satire well beyond what happens in most comedy; it pointed towards finding a way out of a labyrinth of a deadening conformist 1950s culture.” Consequently, Spiegelman read it obsessively: “Mad just became an acronym meaning Mom And Dad - I guess it was more reliable as narrator for me in terms of understanding what was going on.”

Mad also inspired Spiegelman’s first venture when, at 13, he started Blasé, his own fanzine of and about comics: “The quality of it is not nearly as good as even other 13 year-old amateur cartoonists, but the amazing thing was to be in touch with a network of like-minded people. Before that I was just stuck with whoever happened to live on the five square block that I was growing up on.” And it was Blasé that gave Spiegelman his first big break via Topps, a bubblegum company that produced baseball trading cards alongside its candy.

“I was about 14 and I called Topps - with no good logical reason - in order to see if there was any way to buy or be given a few of the small drawings done by Jack Davis, one of the holy trinity of the original Mad artists, so I could look at how his drawings are made on an original piece of paper,” he remembers.

“I don’t know how, but I got transferred to the head of the creative department, so I’m talking to him and explaining that I have this magazine and I want to be a cartoonist. He was really kind and said, ‘Well, why don’t you come down and bring your magazine, and we’ll swap’. And so I did, and that person, Woody Gelman, became really pivotal in my life. Unbeknownst to me, he kept me on file. Years later, he showed me my magazine with a note paper clipped onto it that said, ‘Call this kid when he turns 18’.

Baseball was one of the nightmares of my life; part of what made me a cartoonist was just avoiding baseball

“And so, after not hearing from him since I was 14, at 18 I got what turned out to be a summer job first, and then they created a job for me that hadn’t existed before, of writing and drawing. That man, and Topps, were my Medicis, they were how come I could afford to be an underground cartoonist and not completely starve - although I was never into sports as a kid, which made it especially karmic that part of my job was designing sports cards. Baseball was one of the nightmares of my life; part of what made me a cartoonist was just avoiding baseball.”

With the secure foundation of a job at Topps, and through connections made in the course of his work on Blasé, Spiegelman was able to get involved in the underground comics community and start to find his voice as a creator, which is where Maus, the story of his parents’ experiences in Auschwitz, really began.

“I’d already done a three-page story for an underground comic anthology while living in New York in 1972, and it seemed like deeply unfinished business,” he explains. “I knew I had to go back to it someday. Those were the beginnings and stirrings of me as a cartoonist with a singular voice.”

Initially, Maus was published in Raw, the anthology that Spiegelman founded with his now-wife Françoise Mouly: “I meet this woman playing hooky from architectural studies in France, and we hit it off. She was not sure what she really wanted to do, but as we talked it became clear that it had something to do with books; she wanted to make them, publish them, be them. So that led her to a printing course, and eventually we had a printing press in our four-storey walk up loft and that started us off.”

Their idea was that Raw should be “a place that would let comics be comics”, and that included Maus, which was serialised from 1980 until 1991, and became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. It’s now considered one of the most important and influential comics ever written.

All I really wanted to do was make a long comic book that needed a bookmark

“I’m just sort of lucky that it’s got grandfathered into a category that now exists called ‘graphic novels’, which didn’t exist back when Maus was being made,” says Spiegelman. “All I really wanted to do was make a long comic book that needed a bookmark.”

Today Spiegelman describes his feelings towards Maus as “ambivalent and grateful”. “It’s amazing to have something that landed so intensively well,” he says. “But no matter what I do, I will always have a five hundred pound mouse chasing me around. I do always feel that I’m in my own shadow.”

Having said that, as he reaches 70, Spiegelman says he finally feels he’s worked some things out: “This seems like the right point to talk about my recent insight. There were certain points where I became interested in the higher arts, and I got to think about paintings as large comic book panels, and therefore not to be dismissed as lightly as I had, and then I discovered expressionism, cubism, post-impressionism, surrealism, and all that. And now, now that I’m turning 70, finally I’ve realised the “ism” that I work in, which is, if you’ll pardon the expression, fuckitism.”

Embracing the school of fuckitism has allowed Spiegelman to get involved with all sorts of projects in different media, from stained glass windows to dance choreography. He’s currently working on a secret project with Neil Gaiman, as well as some lithographs on slabs of stone for a gallery in Paris: “It’s taking advantage of a life Maus offered me, which is that people say: ‘Oh, he stumbled on to something once, maybe we should let him try again! Let’s get out of his way and see what he makes!’”

Another project he’s involved with is Resist magazine, which his wife and daughter Nadja created after the Women’s March following Trump’s inauguration. Comparisons between Trump’s America and the Hitler-run Germany that Spiegelman so memorably depicted in Maus are not new, he acknowledges: “Fascism has a lot of different guises, and ways of happening, and America has always had the schizophrenic insistence on individualism and a streak of authoritarianism both running concurrently for as long as I can remember. If it wasn’t going to kill us, it would actually be a pretty good television show.”

America has always had this insistence on individualism and a streak of authoritarianism running concurrently. If it wasn’t going to kill us, it would be a pretty good TV show

Spiegelman is supposed to be working on a project called In the Shadow of Trump Towers, a companion to his work reflecting on 9/11, In the Shadow of No Towers but so far he’s struggling: “I’m too deep in the shadows. So far I feel defeated, as an artist, by Trump; I haven’t been able to figure out how to make him more ridiculous and contemptible than what a cartoon can do. It isn’t adequate to just laugh and say ‘bad hair, small hands’, because it’s so fucking dangerous. It’s like having a chimpanzee flying a plane. A malevolent chimpanzee.

“So thus far, as I watch this daily reality show, I can’t figure out whether it’s a comedy or a tragedy. If it all goes away then it’ll be ‘wow, that was a hell of a ride, I’m amazed we survived’. But if we don’t, it requires a different tone for whatever cockroaches evolve to be able to read the cartoons we make.”

Spiegelman is no stranger to political cartoons, and drew several controversial covers for the New Yorker: “It’s one of the accomplishments I’m prouder of, bringing the scandalous cover to the New Yorker. It started something, which Françoise is now involved with on a weekly basis as the art editor, making it very much an ongoing diary of the zeitgeist, and a provocative one at that.”

All the things Spiegelman is most proud of have subversion in common, and he cites his early work at Topps designing cards and stickers “which were exceptionally subversive - passing along the Mad comics lessons I’d had as a kid, damaging the psyches of a new generation”. He also admits to being proud of the impact his original work has had: “A certain approach to comics developed; I began to poke at what comics could be, teasing out a certain strain, and it really looked like I’d stumbled onto something genuinely new, and I’ve seen it have a real strong effect on other artists.”

When it comes down to it, among the sarcasm and jokes and anecdotes, Spiegelman is sincere, inspiring and enthusiastic when it comes to his real work - that of creating and sharing comics, his own and other artists.

“I guess the only universal advice is to follow that muse - maybe it will take you somewhere important and interesting. Keep it important and real for yourself. I’ve never been a very prolific artist, but I make a thing because I can’t not make it anymore. And if you can follow that, you can be a fuckitism artist from an early age, rather than waiting until you’re haunted by a seventieth birthday!”