- Home |

- Search Results |

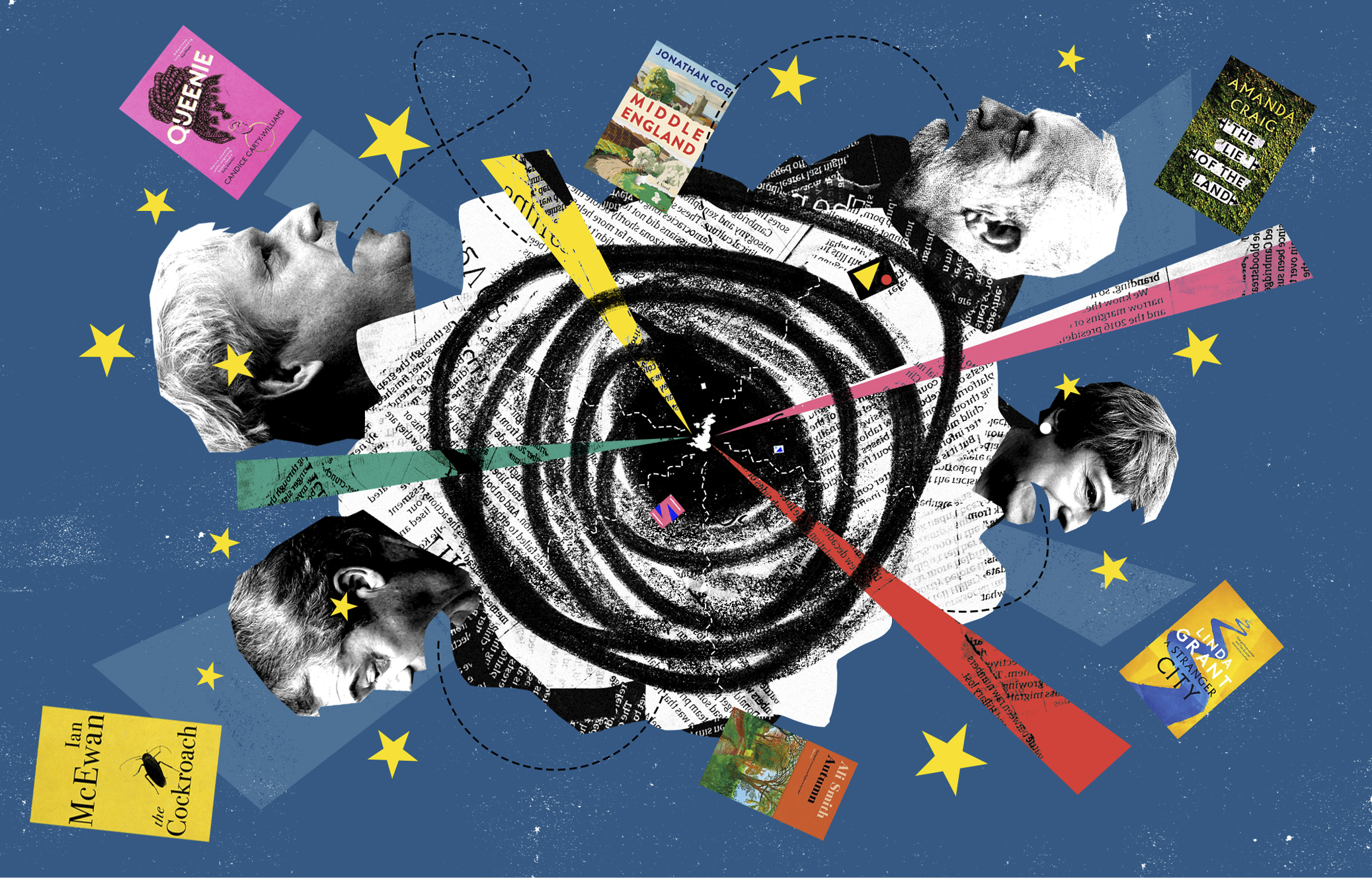

- How Brexit has reshaped the British novel

How Brexit has reshaped the British novel

From dystopia to satire to State of the Nation fiction, the UK's prolonged exit from the European Union has had a huge impact on the work of some of our best novelists, and helped inspire many new voices. Has Brexit led to a golden age of fiction?

Brexit is here. Today the UK will officially leave the EU, more than three-and-a-half years after voting to quit. Frankly, it feels even longer, given the oceans of angry ink spilled on both sides of the debate. Who, you may wonder, is doing the necessary work of transforming the raw emotion of the most divisive political issue in a generation into words that can help us understand what has happened, and why, and what comes next? Or to put it another way: how has the British novel responded to Brexit?

For a recent example of how fiction has absorbed and reflected contemporary politics, look no further than Ireland, our near neighbour culturally and geographically. The country had a much starker financial crash than the UK after 2008, following the (not quite) endless rise of the Celtic Tiger years. The novels addressing the crash began to come a few years later, such as Anne Enright’s The Forgotten Waltz in 2011 and Claire Kilroy’s The Devil I Know in 2012. These are very different books, which could loosely be described as romance and satire respectively, but both take a sceptical backward look at what they see as the madness and vulgarity of pre-crash Ireland, blaming the materialist crescendo of the Celtic Tiger on the ruling class, with the writer looking sceptically on from outside. As we will see, the energy released by this process has led to a rich new period for Irish fiction – but will Brexit have the same effect in Britain?

The novels addressing Brexit that have been published so far have ranged from sinister to comic and much inbetween, and the motivations behind them have varied. Some works of fiction are formed by the historical moment and respond to it naturally; others grapple consciously with a State of the Nation approach; others still try to see ahead to where we might go next. But all do this by telling a story, zooming in on the detail to show how a political earthquake shakes people individually.

'Perfidious Albion's dark world view seemed to fit perfectly'

There’s the out-and-out dystopia, which views Brexit as a symptom of a wider political horror story that has been gripping Britain lately. Sam Byers’ Perfidious Albion (2018) is set in an England where ‘Brexit has happened and is real.’ (This sentence from the blurb is a timely reminder that, two years ago, we were innocent enough to wonder whether Brexit really would go ahead.)

Byers’ world in the novel is a gross-out portrayal of political cynicism and internet culture, where reality is filtered through clickbait news and the alphabet soup of social media, featuring a UKIP-like political party called England Always. Perfidious Albion, Byers says, is not strictly about Brexit but is nonetheless ‘entirely about the forces that were unleashed by the referendum’ such as ‘the mainstreaming of far-right views.’ Like many Brexit novels, Perfidious Albion was begun before the EU referendum in 2016, but its dark world view seemed to fit perfectly the real-time effects of Brexit, which then became a focal point for the novel.

Brexit has also given us a range of novels which seek to represent more closely the political reality of our new world: the divided kingdom, the challenge to multiculturalism, the evergreen uncertainty. One of the most celebrated of these is Ali Smith’s Autumn (2016), published hard on the heels of the EU referendum. It riffs on Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities as a way of discussing the split personality in our society that Brexit brought out of the shadows into the light: ‘All across the country, people felt it was the wrong thing. All across the country, people felt it was the right thing. All across the country, people felt they’d really lost. All across the country, people felt they’d really won.’

But Smith was clear, writing in the Guardian in 2019, that Brexit itself was a symptom, not a new condition. ‘Brexit’s divisions? they aren’t new. Brexit has just made them visible to us all.’ At one point in the novel, a character passes a house on which someone has painted GO HOME, and below is scrawled the response: WE ARE ALREADY HOME THANK YOU. Autumn was named by the New York Times as one of its ten books of the year, a portrait of the UK at a time of crisis, in sympathy with America’s own ‘perplexing moment’ after the election of Donald Trump.

In a similar field of political realism is Linda Grant’s novel A Stranger City (2019), about London after the referendum. ‘I was thinking not so much about leaving the EU, but about the idea of home,’ she said on publication. In her novel, immigrants from Europe who have considered the UK their home for many years, begin to wonder ‘Is this really my home after all?’, and the book shows some of the anti-immigrant violence that happened after the vote.

'Novels, however political, are about people'

Grant says now that she didn’t want to write about people arguing the politics of Brexit, but to show ‘it going on, inexorably in the background, affecting people in large and small ways.’ She wanted also to capture this moment, the end of an era, aware that many of the European languages she heard in London ‘wouldn’t be heard in twenty years’ time’.

Novels, however political, are about people, and although the Brexit vote – like the financial crash in Ireland – was a sudden shocking event, it is what comes before and after that inspires writers, because of what this tells us about our national character. It’s apt that some of the responses to Brexit in fiction have been comic or satirical, which chimes with the great British tradition of coping with a crisis by laughing at ourselves.

Jonathan Coe’s satirical novel Middle England (2018) takes characters from his earlier novels The Rotters’ Club and The Closed Circle and puts them through the meat grinder of Brexit. Yet Coe’s novel, for all its relentless political detail which covers not just Brexit but the UK’s coalition government and the London Olympics, comes to the same conclusion as Ali Smith’s more abstract approach: that Brexit was a symptom of an underlying condition. ‘The referendum wasn’t about Europe at all,’ says one character. ‘Maybe something much more fundamental and personal was going on.’

Coe’s decision to use a set of characters from his earlier books for Middle England was a stroke of genius: any novel attacking the political class needs characters the reader can identify with and root for, so it works perfectly to use those that many of Coe’s readers are already invested in.

But good satire should, while making us laugh, seek not to trivialise its concerns or its characters. Amanda Craig’s 2017 novel The Lie of the Land is both comic and serious. It’s set after Brexit and involves a liberal couple from north London who are forced to downsize and move to Leave-voting Devon after the financial crash (showing, incidentally, how the political issues of one decade can drive the next). As with Coe, Craig’s novel shows that fiction that seeks to persuade politically must be empathetic and inclusive. As she puts it, ‘Leavers are not ignorant, racist bigots. They may have blamed the wrong target for their woes but these are real grievances.’

Like Smith and Byers, for Craig Brexit represented the end result of another phenomenon: ‘the widening division between the country and the city.’ And – usefully for a novelist – the inbuilt conflict meant that ‘Brexit gave us the best excuse for a plot since World War 2.’ Craig sees satire, which seeks to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted, as a natural response to Brexit, which ‘is going to do the opposite to both those things – especially the latter’.

'Brexit has been irresistible even to perhaps the UK’s most acclaimed literary novelist'

But as well as looking directly to the future through dystopian fiction, a novel can act as a warning by considering our current politics as an analogy with the past, which Melissa Harrison did in All Among the Barley (2018). Harrison’s novel is set in rural Suffolk in the 1930s and features a political movement that seeks to ‘preserve the health and purity of our English soil.’ Here, Brexit is seen as a product of toxic nostalgia that looks dangerously close to the far-right movements of the 1930s. Harrison’s main character in All Among the Barley is suspicious of this rose-tinted rear-view mirror: ‘To make an idol of the past only disfigures the present and makes the future harder to attain’. And Harrison describes her book in part as ‘a warning about the seductive, dangerous, simplistic answers that extremism of any kind seems to offer’.

The temptation to grapple with Brexit in fiction has been irresistible even to perhaps the UK’s most prominent and acclaimed literary novelist, Ian McEwan. His novella The Cockroach, which uses a Kafkaesque metamorphosis conceit to mock the hard lines of Brexit politics, is more light-hearted than angry. ‘The only solution was laughter - laughter from despair,’ he said in an interview in The Times. ‘I can’t change the course of events, but I had to deal with this matter in writing to get it off my chest.’

Brexit-related novels may be wide-ranging, but there’s one type clearly missing, whether they consider the subject as horror, satire or lament. All these books, even when understanding both sides of the Brexit argument, are coming from a broadly Remain point of view. If there are any pro-Leave novels – ones that portray Brexit as a success, an unalloyed good thing and cause for celebration – they’re well hidden. Why has this happened?

Writers – especially of the sort of literary fiction that gets reviewed and written about – tend to be liberal, left of centre politically and pro-Remain. ‘I suspect that most novelists and artists are left of centre because we are always pushing back against the status quo, which tends to be on the Right,’ says Amanda Craig.

But also novels themselves, points out Sam Byers, are part of Western literature which is ‘inextricably rooted in continental Europe, particularly France and Germany’ which are regarded as long-established ‘seats of culture’. An ingrained identification with Europe is more likely to lead to fiction that is sympathetic rather than hostile to the European Union.

And if writers skew to the left, what about the political stance of novel readers, the people whose purchasing decisions determine which books will succeed and – further back in the chain – which ones will be published in the first place? A UK poll in 2014 found that supporters of political parties on the right were less likely to be regular readers than supporters of political parties on the left – which could suggest that readers also tilt slightly towards Remain.

Why do we want to read fiction about contemporary politics anyway? Melissa Harrison believes that novels – like all art – serve a similar function for society that dreams do for the individual: ‘postcards from the subconscious, scribbles on the seismograph, clues to who we are and how we feel about ourselves.’ They help us view from another angle the world we are too close to see.

Novels are not news reports, or a hot take on current events. They take a long time to write, their gestation period typically measured in years; novelists need time for underlying themes to percolate into characters and stories. We should be glad about this, as it means the books that result from Brexit are more likely to be – adopting Ezra Pound’s definition of literature – news that stays news.

We can see this necessary time lag in other literary responses to major events of the 21st century. The novels inspired by 9/11 which seem most likely to endure – the likes of Claire Messud’s The Emperor’s Children, Don DeLillo’s Falling Man or Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist – were all published at least five years after the World Trade Centre attacks.

What we have seen so far, then, are Brexit novels that are really about the underlying factors of which Brexit is a symptom – social division, city vs country, intolerance – and guess at what might come. With today’s departure from the EU, Brexit moves from a theory to a fact, so as the UK begins its journey toward a new relationship with the EU, where will Brexit fiction go next?

We might look again to what happened in Ireland. More than a decade on from the crash of the Celtic Tiger, novels are less likely now to deal explicitly with the bust and its aftermath. But what we have seen is a new generation of bold, vigorous fiction from writers like Eimear McBride, Gavin Corbett, Lisa McInerney and Kevin Barry: books that shake the reader and alchemise the anger at Ireland’s recent past into fizzing, unpredictable language and innovative forms – an energy that wasn’t there during the boom years.

And in the UK, as Brexit becomes the new normal, and with a right-of-centre government in power for the next five years, we might expect to see a similar outflow of creativity in the British novel. Perhaps it has already begun, with zestful books showing different sides of modern Britain published recently like Isabel Waidner’s We Are Made of Diamond Stuff, Guy Gunaratne’s In Our Mad and Furious City and Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie. Austerity, adversity and opposition have always proved to be fertile ground for the arts: in Henry de Montherlant’s words, ‘happiness writes with white ink on a white page.’ The form and content of the Brexit novels that will be written are not yet known to us – not yet known, even, to their authors – but we will all be richer for them in the end.