- Home |

- Search Results |

- The Lost Words, one year on

The Lost Words, one year on

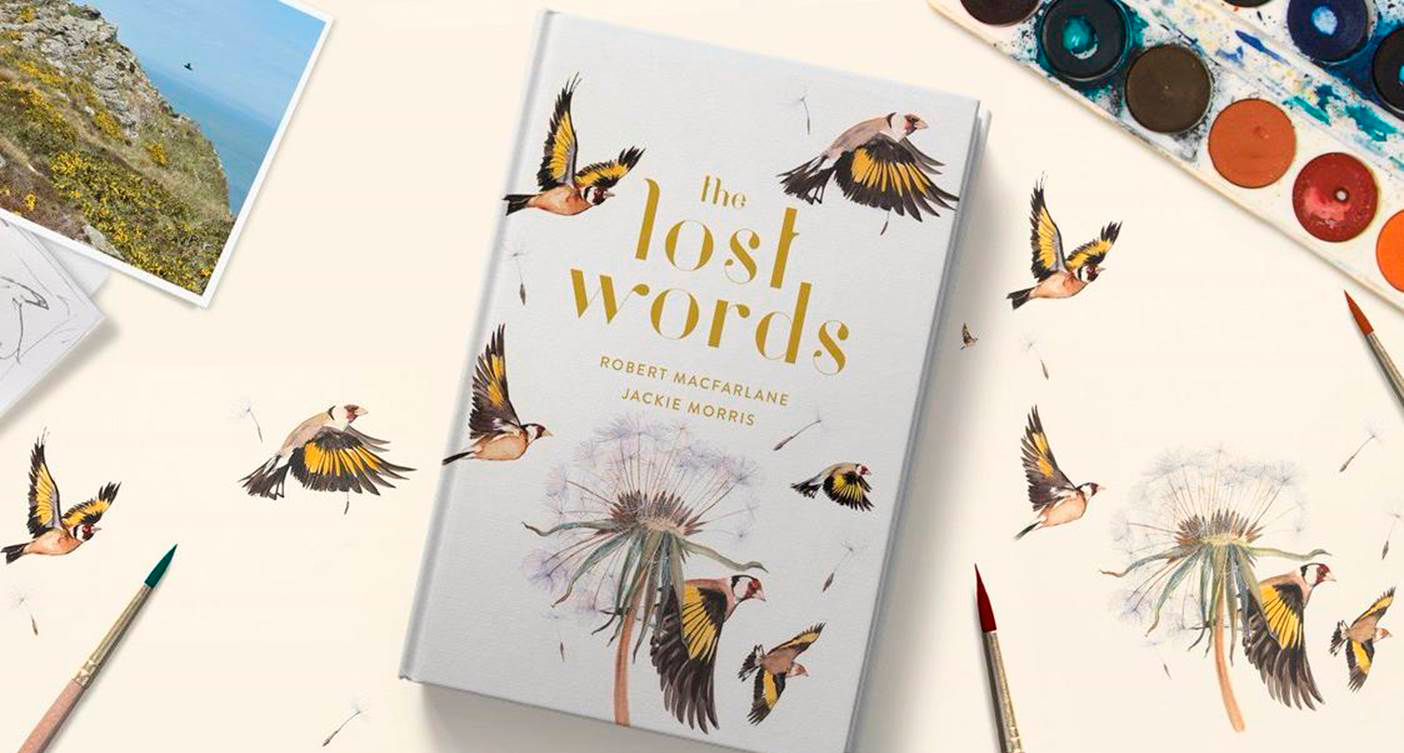

It's been one year since The Lost Words was published - a gorgeously illustrated book that conjures lost words and and species back into our everyday lives. Rob Bushby gives an overview of the first year in the book’s life.

Origins

Published a year ago today (October 5th), The Lost Words is on its 8th reprint after having found its way into the lives of hundreds of thousands of people across Britain and beyond. It’s been described variously as ‘a cultural phenomenon’ and ‘a revolution’ by Chris Packham, ‘a collaboration of words, images’, ‘a wonderful and powerful grimoire’ - a book of magic spells and invocations ‘for people, not children’, ‘a beautiful protest’, ‘a remembering (but not yet an epitaph)’, and ‘the largest I Spy book in the world’. In May it won the Children’s Book of the Year Award jointly with The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Planted as an acorn last autumn, in twelve months The Lost Words has flourished into a remarkable wildwood.

The book’s origins – a direct reaction to nature words dropping out of the Oxford Junior Dictionary due to their lack of use by children – were told in a series of blogs by its instigator-illustrator Jackie Morris, written before the book appeared in the world. “Robert Macfarlane and I tentatively began a working relationship around the re-wilding of language” says Jackie. “It’s a heartsong from us both.” And whilst described as ‘a furious book’ by Robert and ‘real politics’ by Jackie, it’s a response that’s fundamentally both hopeful and challenging: “It’s a celebration of word and image working in a symbiotic way to, we hope, delight the eye and ear. It is a catalyst for creativity. It is, for now, the best we can do.”

In a widely read essay for the Guardian, ‘Badger or Bulbasaur– have children lost touch with nature?’, written to coincide with publication, Macfarlane gave a social, literary and philosophical context for the book. He argues that our loss of very basic ‘nature literacy’ is both a function of, and a contributor to, our growing isolation from it – and the ‘species loneliness’ that results.

Resources

The Lost Words has triggered an astonishing volume of conversation, creativity and action. Responses to its ‘spells’ and images have flown in different directions like dandelion seeds on the wind, emerging independently rather than sought out, constantly taking Robert, Jackie and publishers Hamish Hamilton by surprise.

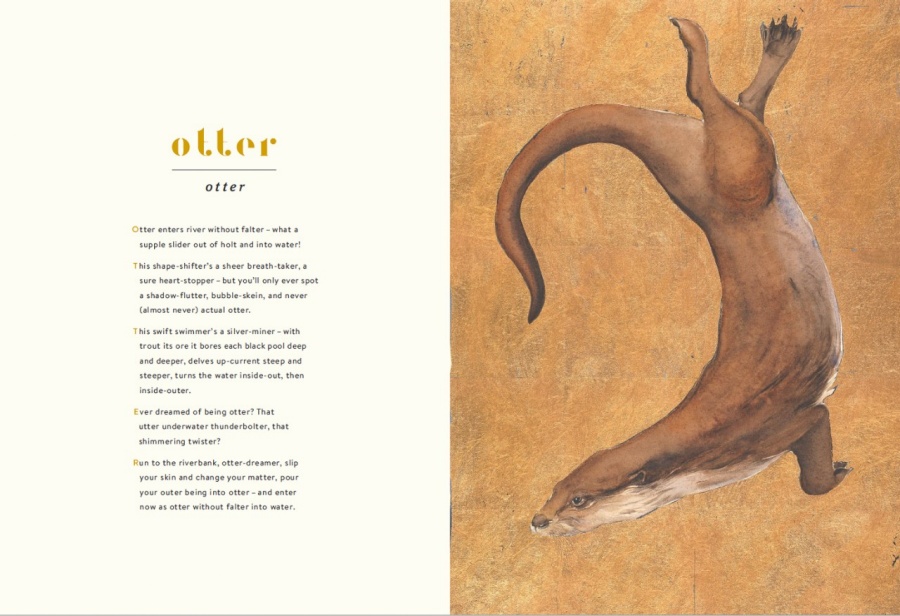

Recognising the potential for the book to be used by thousands of schools and families around the country, Literacy and English Adviser Eva John collated ideas, challenges, connections and further reading for each Lost Word. Her Explorer’s Guide is for teachers, youth workers, parents - anyone in fact - to prompt looking, learning, making and dreaming about the natural world and our part in it. Coinciding with a “Beautiful Book Award” from Books Are My Bag Readers, a simple Word document was out of keeping, so staff at the John Muir Trust designed the Guide to be more of a piece, a visual part of the family. Free poster downloads were added to a web page of information – not only nature poster-boys Kingfisher and Otter but the everyday, nearby ‘little sun-of-the-grass’ Dandelion, with Conker and Bramble as autumnal additions.

Responses

Most striking perhaps has been the extent of active responses. Reading a book is generally a passive exercise, but The Lost Words has stimulated reading (collectively, aloud) and writing, drawing and discussion, and spanned school subject areas including art, English and literacy, geography, science, numeracy, field study trips, outdoor learning, citizenship, ICT, jewelry design… It’s found a natural habitat not only in schools but in homes, libraries, colleges, woods, nurseries, galleries, older-life communities and hospices, gardens, dentist waiting rooms…

“We have been sent probably thousands of photos and videos”, says Robert. “Children are very often trying to enter the book with almost their whole bodies…The ‘space’ in the book is an invitation, beckoning them to come into the imaginative world of The Lost Words.”

Just look on social media, #TheLostWords, or a ‘Lost Words for Schools’ padlet, or word search, for a flavour:

- Lochinver Primary School pupils “hunkered down in a tent in Culag Woods…and took it in turns to choose one spell and read it out loud. It was magical, with the beating rain offering a dramatic rhythm to the spoken word.”

- Director of Open Book and The Belonging Project Marjorie Lotfi Gill: “Today we combined Edinburgh Book Festival’s Freedom theme with The Lost Words. We asked our Open Book Reading migrant/refugee readers about freedom and loss in language. Answers included Kurdish for mum (yade, atê), a father’s voice, and hearing ‘school’ in Arabic”.

- Students with particular social, emotional and wellbeing needs at Cardonald Primary School in Glasgow planned their whole John Muir Award activity around the words and art of The Lost Words, using a greenspace opposite school to focus on five featured words: magpie, raven, heather, ivy and acorn. Class teacher Mrs Hunter: “It’s increased confidence and engagement, particularly in reading and speaking in a class setting.”

- The volunteer-run Elson Library Art Group painted all the Lost Words and donated their art work to raise funds for ‘The Lost Words in Communities Conservation Project’ set up by Hampshire Library Service.

- From Ed Harkness of Stepping Stones, a Norwich-based provider of training and volunteering opportunities for adults with learning disabilities: “The students have been responding with drawings, photos, creative writing and even the start of a song!! They found a puffball mushroom in the woods and wanted to collaborate to make an Acrostic like the poems in The Lost Words. Brilliant!”

- On her John Muir Trust Wild Day, Rebecca Logsdon rediscovers her own lost words. “Reading this with my son, we both enjoyed finding the hidden words…But I want to ask ‘do we really know these nature words?’...It leads me to ponder about the words that I might have lost sight of in my daily life and how nature helps me see them again…Quiet…Focus…Flow…Slow… Playful…Gratitude.”

Crowdfunders & campaigns

“Are there any plans to ensure a copy of The Lost Words is in every primary school? I’d like to make this happen in Scotland. I’m inspired to start a one woman mission,” boldly tweeted Jane Beaton within a week of publication. “This is deeply astonishing and moving to hear, Jane” replied Robert. “Let’s make it happen!” And so it did, with £25,000 generously donated to reach a Crowdfunder stretch target that included Secondary and Special Schools – 2681 in all. More than twenty campaigns followed and continue, from Wales to Dorset to Yorkshire and for care homes and hospices as well as schools, with discounted pricing from the publishers and regular top-up ‘otter-auctions’ from Jackie.

Exhibitions, theatre, music

A partnership with Compton Verney Art Gallery established a touring exhibition of words and original images that has graced London’s Foundling Museum and broken visitor records at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh this summer. “People of all ages left the exhibition and wandered back through the summery Garden more attuned and alert to the natural world about them” said Head of Exhibitions and Events Ian Edwards. “Exceeded expectations!”…“The most beautiful exhibition we’ve seen – ‘The Lost Words’ won’t be lost on us”…“I am Raven!” resounded the Visitors’ Book.

The book’s ‘spells’ have been adapted as a choral work by a children’s choir; composer Kerry Andrew has created evocative sound art and visuals for Bluebell and Wren. There’s an outdoor theatre companion to the book from “Seek Find Speak”, and a commissioned musical project for 2019, Spell Songs.

Resonating

“This book, it’s fair to say, is resonating”, says Daegan Miller in a recent interview, Protest Can Be Beautiful. The piece reflects on reasons why “a book has broken out of its usual bounds and…become a focal point for the powerful hopes and fears that circulate around the questions of our relationship with the living world, our relationships with children and childhood, and our relationship to…the era of planetary-scale environmental degradation”.

Why has the book resonated so powerfully? Its interest is in the familiar and accessible: ‘nearby nature’. It’s of high quality in every way. It doesn’t hector, isn’t didactic, whilst raising vital issues about what we are losing and how we might save it. It trusts the reader and their intelligence, whatever their age: “I love that there isn’t anything like a key on how to use The Lost Words” says Jackie. The emotional response and concern that it invites is present – clearly – in society, if latent. Three quarters of 11-25 year olds enjoy spending time in nature and consider nature to be important to them. The proportion of adults visiting nature at least once a week has increased from 54% in 2010 to 62% in 2018.

Inadvertently perhaps, it embraces much of the environmental step-change good practice guidance from Common Cause, global leaders in values and framing: engage people as though they are interested in and committed to making things better; be rooted in the broad range of ‘compassionate’ values (“and bring creative flair to tailor your communications to resonate with different audiences”!); avoid appealing to ‘self-interest’ values; collaborate beyond the environmental sector. Tick, tick and tick again.

And whilst Robert and Jackie are acutely aware that “perhaps we shouldn’t think of books as saving the world, but catalyzing uncountable small unknown acts of good”, the past year of responses to The Lost Words has indicated that “small acts can together, cumulatively, grow into change”.