- Home |

- Search Results |

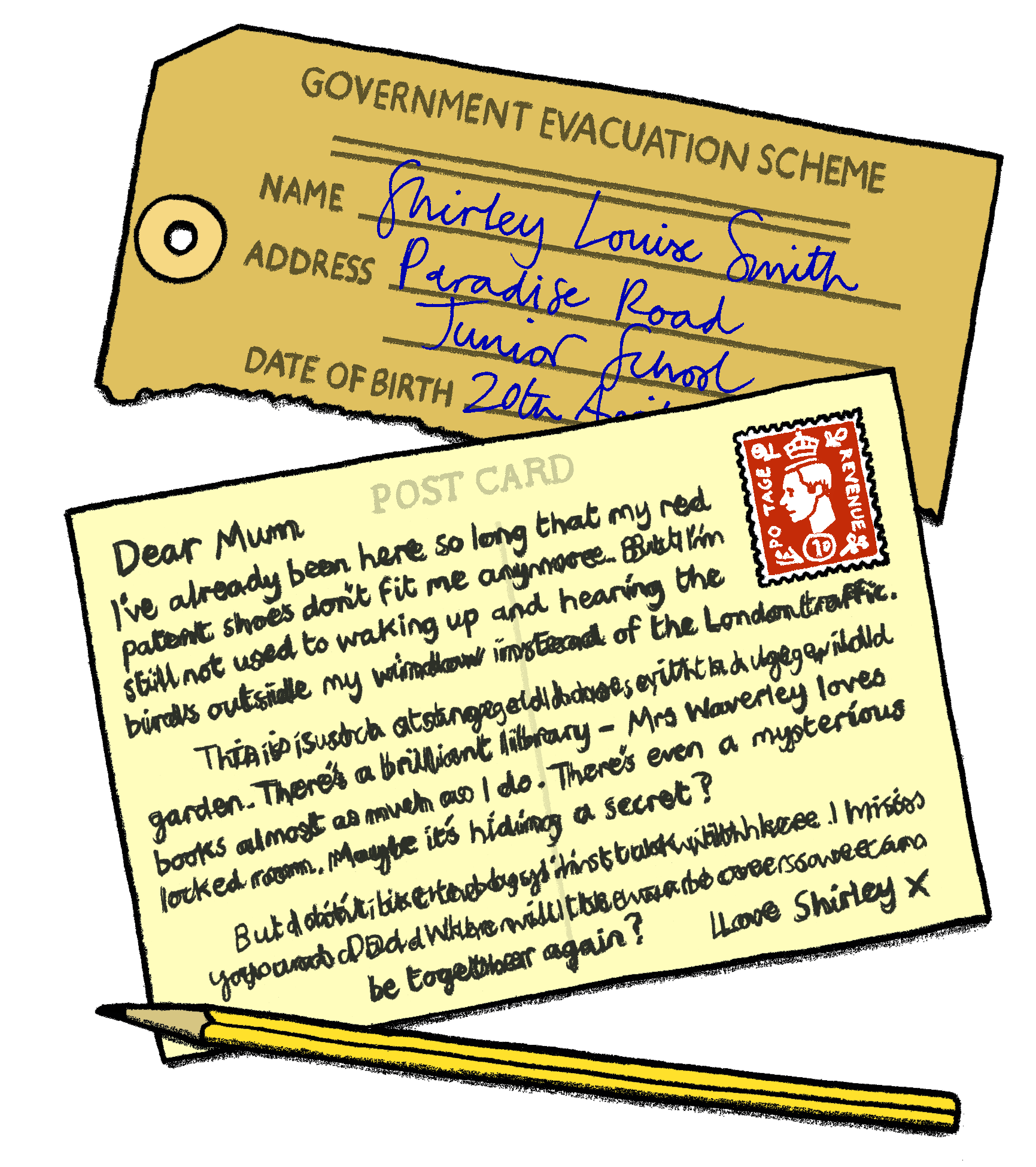

- Wave Me Goodbye by Jacqueline Wilson

Wave Me Goodbye by Jacqueline Wilson

September, 1939. As the Second World War begins, 10-year-old Shirley is sent away on a train with her schoolmates. She doesn’t know where she’s going, or what’s going to happen to her when she gets there. All she has been told is that she’s going on ‘a little holiday’.

Would you like to go on a little holiday?’ asked Mum, the moment she’d shaken me awake.

I sat up in bed and stared at her.

‘Don’t wrinkle your nose like that!’ she said. ‘You look like a rabbit.’

‘I like rabbits,’ I said. I’d been begging her for a pet rabbit for months. I’d given up on the idea of a dog, because I was at school all day and Mum was planning to go back to work so there would be no one at home to look after it. I tried asking for a cat instead but Mum said they smelled. It was only Miss Jessop’s ginger tom that ponged a bit, and that might not be his fault because Miss Jessop herself was a bit whiffy, so Mum was talking nonsense.

She was clearly talking nonsense now. A holiday? We never went on holidays. We’d been on a coach trip to Clacton once, and I’d paddled in the sea and had a cornet and a sixpenny ride on a donkey. I’d thought it was the best day ever, but the men in the coach drank a lot of bottled beer on the way home and had a rude sing-song. Dad sang too. I thought it was funny, but Mum said it was common and we never went on a coach trip again.

‘Do you mean another coach trip, Mum?’ I asked. ‘No, you’ll be going by train,’ she said.

This was even more exciting. I’d never been on a train before. I loved standing under the railway bridge when they thundered overhead. You could scream all sorts of things and no one could hear a word you were saying.

‘A train!’

‘Yes, a train,’ said Mum. ‘We’ve to be at Victoria station to catch the ten o’clock so we’d better look sharp. What would you like for breakfast? Boiled egg or porridge? Or would you like both?’

I never had both. In fact, most days it was bread and dripping or bread and jam. Now I couldn’t decide. Boiled eggs were good, especially with toast soldiers, but sometimes there was a weird little red thing in the yolk, which Mum said was a baby chick. I felt like a murderer eating a baby, especially when it hadn’t even been born. Ever since I’d eaten boiled eggs with my stomach clenched.

Porridge could be good too, but sometimes it was too sloppy and sometimes it was so stiff it had a slimy edge, and that turned my stomach too.

‘Make your mind up, Shirley!’ said Mum.

‘I can’t,’ I said. ‘Could I perhaps have bread with butter and sugar as a special treat instead?’

‘There’s no goodness in that,’ Mum started. Then she sighed. ‘But all right. You’d better have a glass of milk with it. I’ll bring it up on a tray, shall I? I daresay you’d like breakfast in bed.’ She went downstairs.

I fished Timmy Ted out from under the bedcovers and shook my head at him. ‘Curiouser and curiouser,’ I said, and made Timmy nod in agreement.

I was quoting from my Christmas present – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I’d read it three times in the last nine months, and I agreed with Alice that I only liked books with pictures and conversation. However, I didn’t like all the riddles and the feeling that nothing made sense. It was especially odd when babies turned into pigs and royalty became playing cards.

Mum seemed different too. Why was she making such a fuss of me? And why, why, why were we going on holiday? Indeed, how were we going on holiday when we didn’t have any money? It was the thing Mum and Dad rowed about most. And what about Dad? How could he come on holiday when he’d just gone away to be a soldier?

Mum came back with the wooden tray and my sugar sandwich and cup of milk carefully set out, along with a cup of tea and her pack of Craven A cigarettes and the matches.

I took a quick hungry mouthful of my sandwich while she was lighting up.

‘Mum, what about Dad? Won’t he feel sad if we’re going on holiday while he’s away being a soldier?’ I asked.

‘Don’t talk with your mouth full,’ said Mum, drawing deeply on her cigarette. ‘There’s no need to feel sorry for your dad. He couldn’t wait to get away from us. Honestly, what does it look like, joining up before they’ve even started the bally war!’

‘He’s being brave,’ I said, chewing. ‘He wants to fight for Britain.’

‘Your dad’s not brave,’ said Mum. ‘He squeals every time he sees a spider. Him fight? He couldn’t fight his way out of a paper bag.’

The sandwich turned lumpy in my mouth but I couldn’t swallow. I hated it when Mum talked about Dad like that. I suddenly missed him so much. I took a big gulp of milk and spluttered.

‘Oh, Shirley, for goodness’ sake! And look, you’ve spilled milk all over your sheets, you mucky pup. Here!’ Mum put her hand under my chin and tipped up my face so she could have a good look at me. ‘You’re not crying, are you? Whatever for?’

‘I miss Dad terribly,’ I said.

‘For heaven’s sake, he’s only been gone a couple of weeks!’ ‘Yes, but I miss him so. I’m scared someone might ambush him and shoot him.’

‘You’ve seen too many cowboy films at the Saturday morning pictures! He’s not fighting yet anyway, he’s still at training camp. Now eat that sandwich quick, before I take it off you,’ said Mum.

I ate. Mum watched me, her head on one side. Then she picked up a strand of my hair. ‘Perhaps we’d better give your hair a good wash,’ she said.

‘But it’s Friday,’ I said, puzzled.

‘I know, but I want to send you off clean as clean. I’ve put the immersion on, so you’d better have a bath and get your hair washed. You can use my Drene shampoo if you like.’

I suddenly felt alarmed. ‘Mum, are you kidding me? I haven’t got to go to no hospital for my tonsils, have I?’

I’d had my tonsils and adenoids out two years ago, and I’d been scrubbed from top to toe first. Hospital was really scary and my throat had hurt horribly, though they’d given me ice cream and jelly for dinner instead of meat and potatoes, which was an unexpected treat.

‘I haven’t got to go to any hospital,’ said Mum. ‘How many times do I have to tell you? I don’t want you growing up talking common just because we live in this awful dump now. And of course you’re not going to hospital to have your tonsils out. How can you, when they’ve already been taken out, you daft sausage?’

‘You promise?’ I said, still suspicious. ‘You’re acting all funny this morning.’

‘Promise,’ said Mum, but she suddenly sat on the edge of my bed and gave me a hug, almost tipping the tray over.

That seemed odder than ever, because Mum always said she wasn’t one for lovey-dovey stuff and hardly ever hugged. She hadn’t even given Dad a hug when he went off to be a soldier, just a quick peck on the cheek.

I breathed in Mum’s lovely smell of scent and powder. She rubbed her cheek on the top of my head and gave an odd little sniffle, but then pushed me away. ‘Enough of that,’ she said, as if I’d started it. ‘Get into the bathroom spit-spot and start washing. Don’t forget your neck now, and behind your ears.’ ‘Spit-spot, spit-spot, spit-spot,’ I said, running to the bathroom. I sat on the toilet while the taps ran. Mary Poppins said spit-spot. I loved Mary Poppins. She could be a bit snappy like Mum, and she wasn’t one for hugging, either, but she worked the most amazing magic. She knew some wonderful people too. I especially loved Maia, the youngest of the star sisters, who came down to Earth to do her Christmas shopping. I’d had her as an imaginary friend for a while, and sometimes she took my hand and flew me right up into the sky to meet Orion and the Great Bear and the Little Bear. Sometimes she walked to school with me and held my hand tight when Marilyn Henderson gave me a thump on the back and called me a la-di-da, toffee-nosed nitwit.

Maia still came visiting occasionally, but I didn’t need her so much now because I was the fourth Fossil sister, and Pauline, Petrova and Posy looked out for me. Ballet Shoes was my absolutely favourite book.

I played a quick Ballet Shoes game now, muttering under my breath because Mum hated me playing imaginary games and said I was soft in the head. We discussed our auditions for Madame Fidolia’s new production of Sleeping Beauty, and they all agreed I’d be picked for Princess Aurora, with Posy as a little Lilac Fairy. Pauline hoped she’d get to be the Prince, as there weren’t any boys at our stage school. Petrova wanted to be the hundred-year-old bramble at the end, so all she had to do was sway in the breeze and try to scratch the Prince with prickly fingers. We all laughed at her.

‘What are you giggling about?’ Mum called. ‘I can’t hear any splashing. Get on with that bath!’

‘Yes, Mum,’ I said, and did as I was told.

It was a treat washing my hair with Drene when I usually just rubbed it with Lifebuoy soap. I had to keep dunking my head in the bath to get it squeaky clean. I pretended that each dunk was making my hair grow longer. It sprang out of my scalp inch by inch, right down to my shoulders. I could almost feel it swishing this way and that when I turned my head.

When I wiped the steam off the bathroom mirror and saw that my hair still only came down to the tip of my ears I felt disappointed. I hunched my shoulders up but I couldn’t make it look any longer. While it was wet it did look a bit curly, but by the time I’d rubbed it with the towel it was poker-straight again.

‘Clean vest and clean knickers and clean white socks,’ Mum commanded when I went back to my bedroom. ‘And your pleated skirt and your Fair Isle jumper.’

I quite liked my pleated skirt with its white bodice. I sometimes held out the pleats and pretended it was a ballet dress. I kept Dad’s penknife in the pocket. I’d tried to give it back to him when he went to join the army, but he said I could keep it as a lucky mascot. But the Fair Isle jumper was another matter.

‘It’s too hot, Mum. And it itches. It’s not winter yet,’ I said. ‘Can’t I wear a dress?’

‘Not for travelling. But I’ll pack your smocked dress.’

My smocked dress was my best frock – tiny red and white checks with red gathers across the chest and a proper sash at the back. It was to wear to parties with my red patent shoes, though I didn’t get asked to parties at my new school. I loved my red shoes, though they rubbed under the strap and were getting very small for me now; you could see the outline of my toes under the patent leather.

‘Can I wear my red shoes, Mum?’

‘Well, you’re meant to wear stout shoes. Lord knows what they mean by that. I suppose they mean brown lace-ups, but I’m not putting any daughter of mine in clodhoppers – they’re for boys. You haven’t got any stout shoes apart from your Wellingtons, and you’d look a right banana in those, seeing as it’s sunny. So yes, you can wear your red shoes. Now stand still while I do your parting and tie your hair ribbon,’ said Mum.

I stood still, wriggling my toes before I had to cram them into their red cages.

‘You’re doing that nose-wiggling again. Stop it,’ hissed Mum, a hairgrip in her mouth, ready to stab my damp hair into place.

I was thinking over what she’d just said. ‘They?’ I asked. ‘What?’ said Mum, tying my hair ribbon on one side and pulling it out carefully so the ends were even.

‘Who are they?’ I repeated. ‘You said that they said I should wear stout shoes.’

‘Oh, Shirley, stop your silly questions and hurry up! Did you clean your teeth? I thought not. Now, go and give them a good scrubbing, and then I want you to get your toothbrush and the toothpaste and your flannel – squeeze it out properly – and we’ll put them in my sponge bag.’

‘Shall I get your toothbrush and flannel too, Mum?’

‘You leave me to organize myself,’ she said. ‘Now, let’s get you packed.’ She reached up to the top of my wardrobe and brought down my cardboard suitcase. She blew the dust off and looked at it critically. ‘It’s falling to bits! And what have you got inside?’

She opened it up and stared at my colouring pencils and notebooks and my conker doll’s-house furniture and my old toy tea set and my poor plastic Jenny Wren dolly who had lost her eyes inside her head and now gave me the creeps.

‘For heaven’s sake!’ Mum exclaimed. ‘What’s all this junk? And I thought you’d said your teacher had confiscated your dolly when you took her to school... What’s she doing here? And what have you done to her eyes? That doll cost seven and six, miss!’

‘I’m sorry, Mum. She had an accident and I was scared to tell you,’ I said. ‘Her eyes fell in and now they rattle around inside her and won’t come out again. It wasn’t my fault – they just did it, honest.’

‘Honestly. And you’re making it worse, lying like that. You did it, didn’t you?’

Of course I’d done it, though I didn’t mean to. I was playing with Jenny Wren, even though I knew I was too old for such games. After all, I’d turned ten this summer. Jenny Wren was more of an ornament than a doll, but that meant she was pointless. I’d been taken to Bertram Mills Circus at Olympia for a special Christmas treat, so I turned Jenny Wren into a tightrope walker, tying my dressing-gown cord between my wardrobe handle to a knob on my chest of drawers. She was balancing so splendidly in her little knitted socks that I let go for half a second.

She fell on her head and there was an awful click, and then she didn’t have eyes any more, just awful dark blanks, and I had to shut her up in the suitcase quick. Quickly.

‘Well, it’s your loss, because you’re allowed to take one toy, and that doll was your best toy but you can’t take her like that – she looks shocking,’ said Mum, tipping everything out of the suitcase helter-skelter on to the floor.

‘Timmy Ted’s my best toy,’ I said.

‘But he looks awful too,’ said Mum, holding him up by one paw and sniffing disdainfully. She had put him in the wash because he was getting so grubby and he’d never been the same since. He’d gone all droopy and his snout was lopsided, but I still loved him, unlike poor Jenny.

Luckily Mum had dropped him and started fussing about the state of the suitcase instead. ‘Look at that handle! That’s not going to last, is it? The stitches are already unravelling at one end. And it looks so shoddy. Oh dear Lord, it’ll come to pieces before you get there,’ she said.

‘Get where?’

‘The country,’ said Mum, abandoning my suitcase and going into her bedroom.

‘Where in the country?’ I called. I was surprised. Mum had never been keen on the country. She always said there was nothing there but a load of fields and trees, so what was the point.

‘Oh, do give over, Shirley,’ said Mum. ‘Clear up all that mess on the floor and stow it back in that old suitcase. You’ll have to use this one.’ She brandished the big, glossy brown samples suitcase.

‘But that’s Dad’s!’ I said, shocked.

Dad was a commercial traveller, a brush salesman. ‘Any sort of brush, madam – nailbrush, toothbrush, hairbrush, clothes brush – every size and shape of high-quality brushes.’ That was his patter. He sometimes pretended that I was one of his customers. Then he’d flip the lid open, and there were all the brushes lined up in neat rows and I’d take my pick.

‘He’s not needing it now, is he? He’s in the army,’ said Mum. ‘But it’s not even his suitcase. It belongs to the Fine Bristle Company,’ I said, pointing to the name inside the case.

‘Yes, well, they won’t be bothering about that now, not when war’s going to be declared any minute. Help me unslot all these bally brushes,’ said Mum, trying to wiggle each one out from under the tight bands keeping it in place.

‘You’re not meant to take out the brushes,’ I said. ‘Dad will get cross.’

‘Dad’s not here, is he? And he took the only decent suitcase with him, so we’ll have to use this and he can jolly well lump it.’

It was very odd seeing Mum putting my washing things, clean nightie, another set of underwear and socks, my smocked dress, my hairbrush, a pack of three hairgrips and a spare ribbon into Dad’s sample case.

‘Now, this toy... Why don’t you take that nice jigsaw puzzle of the map of the world? It’ll keep you busy for ages and it’s educational,’ said Mum.

‘I don’t really like jigsaw puzzles. And you can’t cuddle them,’ I pointed out. ‘Please let me take Timmy Ted.’

‘Oh, all right then,’ said Mum, sighing. ‘Put him in.’

I tried to make a little bed for him in amongst my clothes so he wouldn’t be bumped around inside the suitcase.

‘I just spent ages smoothing out that dress and now you’re getting it all crumpled,’ said Mum, elbowing me out of the way. ‘Right. Nearly done. You can take one book too.’

‘One?’ I said.

‘Yes, well, I know that’s a bit limited, the way you rush through books. You’ll have read it all on the train journey. Perhaps you can slip in two. Choose. Quickly now.’

I knelt on my bed and looked at the row of books on my new shelf. It wasn’t straight and the edges were rough and gave you splinters if you weren’t careful. Dad wasn’t very good at household jobs. I looked at all the books standing in neat alphabetical order. I’d decided I was going to be a librarian when I grew up and was practising. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Ballet Shoes, Black Beauty, The Squirrel,, the Hare and the Little Grey Rabbit, A Little Princess, Little Women, Mary Poppins and Peter and Wendy. I also had Orlando the Marmalade Cat, but it was too big to fit on the shelf, so I’d laid it across the other books, with a little plaster cat made with my modelling kit on top.

I was so pleased with my book arrangement that I often sat up in bed and looked at it for sheer enjoyment. But now my eyes scanned each title anxiously. I loved them all, even Alice. How could I possibly choose?

‘I want to take them all,’ I said. ‘Shame you’ve got to squash all your clothes into the case too, Mum, otherwise there might be room.’

Mum didn’t say anything.

I turned round. I saw her face. ‘Mum?’

‘Hurry up now.’

‘Mum, you are coming too, aren’t you?’ I asked. My voice was suddenly squeaky.

‘Well, no, I’m not coming,’ she said.

‘But you said...’ I went over everything in my head, trying to remember exactly what she had said.

‘So is Dad taking me then?’ I asked.

‘Shirley, have you gone simple? Your dad’s in the army, for pity’s sake.’

‘Yes, but I can’t go on holiday on my own!’

‘You’re not going to be on your own. You’re going to go with lots and lots of other children,’ said Mum.

‘Which other children?’ I asked anxiously. ‘All your school friends.’

I’d started going to Paradise Road Juniors three months ago. My class still called me the New Girl. I didn’t seem to have any special friends, but I had a Deadly Enemy. Marilyn Henderson made my life a misery.

‘I don’t want to go on holiday with my school!’ I said firmly.

‘It’s not just your school, Shirley. It’s children from all over London. You’re all going on this holiday. You’re being evacuated. It’s to keep you safe if those wicked Germans start dropping bombs.’

‘Are they really going to drop bombs, Mum?’

‘Don’t you worry about it. You’ll be safe in the country, having a whale of a time. Now, choose. Two books, if you must. I’d take Alice in Wonderland – it’s not as tattered as the others, and it was your Christmas present.’

I ignored this idea. I chose Ballet Shoes because it was my favourite, and Mary Poppins because I felt in need of a nanny who could do magic. Then I saw Little Grey Rabbit in her soft grey dress looking at me imploringly, so I picked The Squirrel, the Hare and the Little Grey Rabbit too. I clutched all three to my chest.

‘Can’t you count? And why choose those three? They’re all falling to bits. You’ve read that bally Ballet Shoes at least ten times, and Mary Poppins too. Look, the cover’s all torn. And that rabbit book is far too babyish,’ said Mum. ‘You’ve had it since you were five! People will think you’re backward, when in fact you’re a really good little reader.’

‘I want them. Please, Mum. Especially Little Grey Rabbit. She lives in the country and you said we were going to the country. Only now you’re not coming. Oh, Mum, why aren’t you coming?’ I wailed.

‘Because war’s going to be declared any minute, and all the grown-ups have to stay behind and help. Everyone knows that. I’ve got to do my bit. I’ve applied for a job at Pendleton’s,’ said Mum, tucking my three books into the sample case and then snapping it shut.

‘Pendleton’s Metals, where Dad used to work?’ I asked, astonished. Mum had always hated Dad working in a factory. She made him apply for a job in Grey’s department store instead, but that hadn’t worked out, and then he worked in the hat shop which closed down, so then he was a commercial traveller, but he couldn’t sell many brushes no matter how hard he tried, so we’d had to move to Paradise Road where the rents were cheaper, and I had to go to a new school where nobody liked me.

‘It’s not going to be Pendleton’s Metals anymore, it’s going to be Pendleton’s Munitions, making weapons for the army. They’re changing all the machinery over as part of the war effort,’ said Mum.

‘You’re going to work in the factory?’ I asked, trying to imagine her in overalls with her hair tied up in a scarf like the ladies I saw hurrying to work when I went to school.

‘No, you noddle! You know perfectly well I was a trained secretary before I married your father. I’m going to be Mr Pendleton’s private secretary,’ said Mum.

‘Why didn’t you tell me about your job and my holiday and all this?’ I demanded.

‘Hey, hey, watch your tone, young lady. I didn’t want to tell you before because I knew you’d simply get into a state, just the way you are now. And there’s no time for it – we have to get you to that station, and the buses are a nightmare now. Come on. Put your coat on. Wait while I pin this daft label on you.’

‘But I’m already boiling in this woolly jumper.’

‘You do look a bit pink,’ said Mum, sighing. ‘Well, I’ll pin it on your jumper. Keep still – I don’t want to pull any of the threads.’

I peered down at my chest and read the label upside down. I said it aloud. ‘Shirley Louise Smith, Paradise Road Junior School.’

‘I know. Why you have to have a label at your age I don’t know. You’re hardly likely to forget your own name,’ said Mum. ‘Now, put the coat in your case and then we’ll get cracking. I’m going to put on my hat and jacket.’

She went into her bedroom. I undid the case, folded my coat inside, and then very quickly grabbed all the rest of my books and tumbled them on top of my clothes, even Orlando. I put my gas-mask case strap over my shoulder, then snapped the case shut and hauled it off the bed and down the stairs, thump, thump, thump. I could barely lift it, but I didn’t care. I needed all my books with me. I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to enjoy this holiday one little bit.