- Home |

- Search Results |

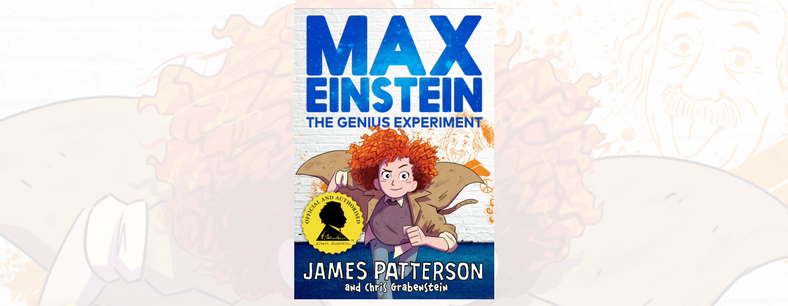

- Max Einstein: The Genius Experiment by James Patterson

Max Einstein: The Genius Experiment by James Patterson

Twelve-year-old orphan Max Einstein (like Albert Einstein himself) is not your typical genius. Max hacks the computer system at NYU, builds homemade inventions to help the homeless, and is recruited by a mysterious organisation to help solve some of the world's toughest problems…

Chapter 1

The stench of horse manure woke Max Einstein with a jolt.

“Of course!”

Even though she was shivering, she threw off her blanket and hopped out of bed.

Actually, it wasn’t really a bed. More like a lumpy, water-stained mattress with frayed seams. But that didn’t matter. Ideas could come wherever they wanted.

She raced down the dark hall. The floorboards—bare planks laid across rough beams—creaked and wobbled with every step. Her red hair, of course, was a bouncing tangle of wild curls. It was always a bouncing tangle of wild curls.

Max rapped her knuckles on a lopsided door hanging off rusty hinges.

“Mr. Kennedy?” She knocked again. “Mr. Kennedy?”

“What the…” came a sleepy mumble. “Max?” Are you okay?”

Max took that question as permission to enter Mr. Kennedy’s apartment. She practically burst through his wonky door.

“I’m fine, Mr. Kennedy. In fact, I’m better than fine! I’ve got something great here! At least I think it’s something great. Anyway, it’s really, really cool. This idea could change everything. It could save our world. It’s what Mr. Albert Einstein would’ve called an ‘aha’ moment.”

“Maxine?”

“Yes, Mr. Kennedy?”

“It’s six o’clock in the morning, girl.”

“Is it? Sorry about the inconvenient hour. But you never know when a brainstorm will strike, do you?”

“No. Not with you, anyway…”

Max was wearing a floppy trench coat over her shabby sweater. Lately, she’d been sleeping in the sweater under a scratchy horse blanket because her so-called bedroom was, just like Mr. Kennedy’s, extremely cold.

The tall and sturdy black man, his hair flecked with patches of white, creaked out of bed and rubbed some of the sleep out of his eyes. He slid his bare feet into shoes he had fashioned out of cardboard and old newspapers.

“Hang on,” he said. “Need to put on my bedroom slippers here…”

“Because the floor’s so cold,” said Max.

“Huh?”

“You needed to improvise those bedroom slippers because the floor’s cold every morning. Correct?”

“Maxine—we’re sleeping, uninvited, above a horse stable. Of course the floors are cold. And, in case you haven’t noticed, the place doesn’t smell so good, either.”

Max, Mr. Kennedy, and about a half-dozen other homeless people were what New York City called “squatters.” That meant they were living rent-free in the vacant floors above a horse stable. The first two floors of the building housed a parking garage for Central Park carriages and stalls for the horses that pulled them. The top three floors? As far as the owner of the building knew, they were vacant.

“Winter is coming, Mr. Kennedy. We have no central heating system.”

“Nope. We sure don’t. You know why? Because we don’t pay rent, Max!”

“Be that as it may, in the coming weeks, these floors will only become colder. Soon, we could all freeze to death. Even if we were to board up all the windows—”

“That’s not gonna happen,” said Mr. Kennedy. “We need the ventilation. All that horse manure downstairs, stinking up the place…”

“Exactly! That’s precisely what I wanted to talk to you about. That’s my big idea. Horse manure!”

Chapter 2

“It’s simple, really, Mr. Kennedy,” said Max, moving to the cracked plaster wall and finding a patch that wasn’t covered with graffiti.

She pulled a thick stub of chalk out her baggy sweater pocket and started sketching on the wall, turning it into her blackboard.

“Please hear me out, sir. Try to see what I see.”

Max, who favored the drawing style she first discovered in the great Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbooks, chalked in a lump of circles radiating stink marks. She labeled it “manure/biofuel.”

“To stay warm this winter, all we have to do is arrange a meeting with Mr. Sammy Monk.”

“The owner of this building?” said Mr. Kennedy, skeptically. “The landlord who doesn’t even know we’re here? That Mr. Sammy Monk?”

“Yes, sir,” said Max, totally engrossed in the diagram she was drafting on the wall. “We need to convince him to let us have all of his horse manure.”

Mr. Kennedy stood up. “All of his manure? Now why on earth would we want that, Max? It’s manure!”

“Well, once we have access to the manure, I will design and engineer a green gas mill for the upstairs apartments.”

“A green what mill?”

“Gas, sir. We can rig up an anaerobic digester that will turn the horse manure into biogas, which we can then combust to generate electricity and heat.”

“You want to burn horse manure gas?”

“Exactly! Anaerobic digestion is a series of biological processes in which microorganisms break down biodegradable material, such as horse manure, in the absence of oxygen, which is what ‘anaerobic’ means. That’s the solution to our heating and power problems.”

“You sure you’re just twelve years old?”

“Yes. As far as I know.”

Mr. Kennedy gave Max a look that she, unfortunately, was used to seeing. The look said she was crazy. Nuts. Off her rocker. But Max never let “the look” upset her. It was like Albert Einstein said, “Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.”

Not that Mr. Kennedy had a mediocre mind. Max just wasn’t doing a good enough job explaining her bold new breakthrough idea. Sometimes, the ideas came into her head so fast they came out of her mouth in a mumbled jumble.

“All we need, Mr. Kennedy, is an airtight container—something between the size of an oil drum and a tanker truck.” She sketched a boxy cube fenced in by a pen of steel posts. “Heavy plastic would be best, of course. And it would be good if it had a cage of galvanized iron bars surrounding it. Then we just have to measure and cut three different pipes—one for feeding in the manure, one for the gas outlet, and one for displaced liquid fertilizer. We would insert these conduits into the tank through a universal seal, hook up the appropriate plumbing, and we’re be good to go.”

Mr. Kennedy stroked his stubbly chin and admired Max’s detailed design of the device sketched on the flaking wall.

“A brilliant idea, Max,” he said. “Like always.”

Max allowed herself a small, proud smile.

“Thank you, Mr. Kennedy.”

“Slight problem.”

“What’s that, sir?”

“Well, that container there. The cube. That’s what? Ten feet by ten by ten feet?”

“About.”

“And you say you need a cage of bars around it. You also mentioned three pipes. And plumbing. Then I figure you’re going to need a furnace to burn the horse manure gas, turn it into heat.”

Max nodded. “And a generator. To spin our own electricity.”

“Right. Won’t that cost a whole lot of money?”

Max lowered her chalk. “I suppose so.”

“And have you ever noticed the one thing most people squatting in this building don’t have?”

Max pursed her lips. “Money?”

“Uhm-hmm. Exactly.”

Max tucked the stubby chalk back into her sweater pocket and dusted off her pale, cold hands.

“Point taken, Mr. Kennedy. As usual, I need to be more practical. I’ll get back to you with a better plan. I’ll get back to you before winter comes.”

“Great. But, Max?”

“Yes, sir?”

Mr. Kennedy climbed back into his lumpy bed and pulled up the blanket.

“Just don’t get back to me before seven o’clock, okay?”