- Home |

- Search Results |

- What re-reading John le Carré taught me

What re-reading John le Carré taught me

Thriller novelist Mick Herron reflects on a lifetime of reading John le Carré ahead of the publication of the late author's final work, Silverview.

My memory tells me it happened like this: I was watching TV; it was 1979. The programme was a new drama serial, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, about the search for a mole within the British secret service – and if ‘mole’ was part of my vocabulary then, it would have been from reading about this very programme. My parents were in their usual chairs. I can’t remember who else was in the room, or whether it was a weeknight, or what time of year it was, but I remember that during the opening scene we watched the characters assemble for a meeting. One – who would turn out to be Bill Haydon, as played by Ian Richardson – entered carrying a cup of tea, on top of which he’d balanced its saucer, to prevent spillage.

"That’s a strange way of carrying his tea," my dad said. "I bet he’s the mole."

Memory also tells me that by the time the second part of the drama was screened I had read the novel, and knew who the villain was, and, if an unconventional manner of carrying cup and saucer wasn’t explicitly cited as an indication of treachery, it probably counted as circumstantial evidence. This was a world of nuance, after all.

But knowing the ending spoiled nothing, and I stayed hooked to the TV version throughout the following weeks, soaking up the atmosphere, the muted palette, the grubby world of le Carré’s Circus, so distantly removed from the glitzy shenanigans of James Bond. And when it was over, the books remained, and it was clear they were there for good.

Books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time

I already had somewhere to put them. My teen years were when I compiled my mental library, without knowing that’s what I was doing. I still carry it everywhere – it puts my Kindle to shame – and, if its shelves are loaded with titles I’ll never take down again (My Friend Flicka, Daddy-Long-Legs), they also contain many which remain touchstones (Emma, The Pat Hobby Stories, Sweet Thursday). And, though others have been added since, le Carré is unique among my schoolboy shelvings in that he continued to work well into my adult life; and he is the only writer among their number to have published a masterpiece that I read as a brand-new book: A Perfect Spy. But it’s the trilogy of the 1970s that lodges most firmly in my mental library: The Quest for Karla, comprising Tinker Tailor, The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley’s People. They’re the books of his I’ve carried longest, thought about hardest and reread most frequently.

Rereading is often deemed comfort reading, and of course it can be. But books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time, emotions inextricably entwined with the feeling of being young. Comfort reading can be the most uncomfortable kind of all.

I mentioned my Kindle. It’s useful when I’m travelling, but there’s a fundamental problem with e-books: they don’t lock a moment in your mind the way their physical counterparts do. I remember buying The Honourable Schoolboy at a bookshop in Newcastle that no longer exists; I remember taking it on a marathon coach journey, the length of the country. And I remember reading much of it in my first ever hammock in blistering sunshine, on my first foreign holiday, not far from Nîmes.

The Honourable Schoolboy’s plot, then as now, bestrides the Far East, but begins in London’s dusty corners, with gossip. Le Carré’s world is rife with bitchery and rumour, with espionage carried out among the filing cabinets: we’re in the world after the fall now, hearing "the last beat of the secret English heart". The Service is broken, Bill Haydon’s damage done, and a photograph of Karla, his Moscow Centre paymaster, hangs in George Smiley’s office. Meanwhile, Connie Sachs, Russia gazer, is taking backbearings – "walking back the cat", as novelist Robert Littell later dubbed it – to find out what Karla knew, what he hadn’t known, and what he hadn’t wanted the Circus to know he knew, or didn’t know... In le Carré’s hands, these cat’s’ cradles of doublethink and counter-bluff are mesmerising, not least because readers can recognise their own talents in this element of tradecraft – trawling through paperwork, finding gaps, making connections: we can do that! We could run away and join the Circus! And we’re familiar, too, with the forlorn realities of office life: petty cash and expense slips, pointless meetings, too many cups of tea and steamed-up windows on winter afternoons.

I say familiar, but I was years away from office life at the time, and, though I now recognise this background of failure and despair as being achingly redolent of Britain in the 1970s, my schoolboy self in his hammock surely can’t have done. And yet I think it was part of what fascinated me, as it does now. Failure has become a leitmotif of the author’s – audible even in those novels written during optimistic times – and to be one of le Carré’s people means accustoming oneself to it; accepting that every triumph knocks hollow, and every mole uncovered reveals the devastation done to the lawn.

Which is why it never ceases to thrill to read that "from these quite dismal beginnings . . . George Smiley went over to the attack."

Not that Westerby’s lot sounded so bad to my teenage self: living on a remote Italian hillside dragging a sackful of books around

Attack begins with recruitment, and le Carré has to do a certain amount of retro-fitting to bring the honourable schoolboy, Jerry Westerby, into play. He’s no longer the faintly ridiculous figure from Tinker Tailor (‘“Too much wampum not good for braves,” Jerry intoned solemnly. For years they had had this Red Indian joke running, Smiley remembered with a sinking heart’), and his ability to undertake an operational role relies on his not having been exposed by Bloody Bill Haydon. "On balance it seems he never got around to blowing the Occasionals," Smiley tells Westerby. "It’s not that he didn’t think you important enough... it’s simply that other claims on him took priority." Well, perhaps. But Haydon was in play for decades, and surely had time to give Moscow Centre the inside leg measurements of anyone who passed through Cambridge Circus, let alone the names of those irregulars known to pick up arms when called. But it’s a required pluck on the narrative strings, the addressing of what would otherwise remain an unanswered question, and is more than justified by the satisfaction of having a minor character move centre stage. "You point me and I’ll march," Westerby tells Smiley in a moment that, for me, captures all that’s most stirring, and most worrying, about responding to the call of duty. Point him and he’ll march, and his marching orders will take him far from the life he’s been living, the familiar bid for freedom that drives le Carré’s men.

Not that Westerby’s lot sounded so bad to my teenage self: living on a remote Italian hillside – where was Lucca, anyway? – dragging a sackful of books around; hiding from a past choked with romantic damage; banging away on a typewriter as he chased a doomed novel. At the time, that pretty much amounted to my ideal existence. But he marches, and, while the operation is technically a success, it comes at great cost: Jerry Westerby, it turns out, does question his orders, and his eventual act of self-determination allows Smiley – and the Circus – to be gazumped. The spoils go to the Cousins, as the Americans are termed in le Carré’s world, and the lesson is clear: our allies can be more treacherous than our foes. With Karla, at least you know where you stand.

And Westerby’s downfall, of course, is brought about by love. Or, put another way, by a woman. This is standard fare in le Carré’s novels, where – the occasional Connie Sachs apart – women exist to provide sex and comfort, or to offer a Grail-like vision of Courtly Love, or to lead poor men round by the nose. Or all three. Later novels may have gone some way to redressing this lack of balance – and several provide pivotal roles for female characters – but, nevertheless, examples abound, the most egregious being Legal Judith in Absolute Friends, whose trajectory careers from unattainable perfection to willing lover to exposure as shallow, status-obsessed and tarnished beyond redemption. But at least she’s given a name, or half of one, unlike ‘the orphan’ in The Honourable Schoolboy, whose main role – sex and comfort aside – is to make poor Jerry feel guilty, a burden he carries long after he’s jettisoned the actual woman on the way to the airport. "When she got out she didn’t even say goodbye: just sat beside the road like the trash she was." "Trash" isn’t le Carré’s word – it’s one he puts into the mouth of the local postmistress – but it leaves a taste. Did I not mind this, first time round? I’ve minded ever since, and new generations of readers will find it hard to overlook.

Like I say, rereading can be uncomfortable.

When the BBC’s Smiley’s People was broadcast in 1982, I watched at least some of it on a tiny portable black-and-white TV in the kitchen of a student house in Oxford. As with Tinker Tailor, I’d read the novel, so the story held no surprises. The thrill came from watching Alec Guinness once more inhabiting the role of Smiley as completely as any actor has ever embodied a character.

And inevitably it’s Guinness I see when I pick up the book again, and am sucked into the narrative. Smiley is summoned to a murder scene – an old spook has been gunned down on Hampstead Heath – and watches while a chatty police superintendent rifles the dead man’s pockets. One Paddington Borough library card, one box Swan Vesta matches partly used. One bottle tablets, to be taken two to three times a day. And one receipt for the sum of thirteen pounds from the Straight and Steady Minicab Service of Islington, North. ‘“May I look?” said Smiley, and the Superintendent held it out so that Smiley could read the date and the driver’s signature, J. Lamb, in a copy-book hand wildly underlined.’

J. Lamb . . . This might be a good moment to mention that one of the main characters in my own spy novels is called Jackson Lamb.

Now, I don’t keep a record of every book I pick up, but I can state with some certainty that the last occasion on which I reread Smiley’s People was 2010 – I know this because I mentioned having done so in an article I wrote in August of that year. By that time I was working on the second of my Lamb novels, and I had no memory, then or later, of having borrowed his name from this source. Which didn’t mean that such petty larceny hadn’t occurred; it simply meant that, if it had done, it had happened subliminally, dredged up from an earlier reading. So, browsing the novel again, I looked for clues as to why this name of all others might have lodged in my mind. J. Lamb’s subsequent appearance is brief, taking up little more than a page, and, if there’s little in his physical presence that brings his partial namesake to mind – ‘He had brown Afro hair. White hands, carefully manicured’ – he does carry the hum of stale cigarette smoke, a grace note my own Lamb would reprise at full volume. And at least one character trait rings familiar: Smiley has questioned the minicab driver under the pretence of having booked his services. Interview concluded, Smiley says, "You can tell your firm I didn’t turn up". "Tell ’em what I bloody like, can’t I?" J. Lamb explains, and drives away almost before George is out of the car.

And perhaps that’s it. Like a secret message tucked into a cigarette packet and hidden on Hampstead Heath: ‘J. Lamb. Very rude man.’ Received and understood.

That 2010 article, incidentally, was partly about the physical appearance of Smiley’s People, as I’d recently been given a first edition as a birthday gift. It was the same edition that I borrowed from my local library back in 1979 or ’80, and has, to reread myself:

a mostly black cover, on which an orange light illuminates five upright dominoes, each in turn reflected in the smooth surface on which they’re standing. If I’d ever given this much thought before, I’d assumed the dominoes were illustrating the principle they’ve given their name to: they’re spaced at just the right distance, so that if one falls, the others will follow. Which is how the plot works, with each tiny step Smiley takes leading inevitably to the next. Walls, eventually, come tumbling down. But now I’ve noticed that all these dominoes are doubles . . . It’s a more mysterious illustration than I’d originally thought, and picks up on the themes of twinning that run through the trilogy, so many of whose characters are battling against their dark or brighter angel.

It matters to me that my copy of Smiley’s People is identical to the one I originally read – when I pick it up, I feel my younger self tugging at my sleeve, asking for his book back. And both our hearts still clench on rereading those final few chapters, the tensest, most fulfilling passages in all spy fiction. Again I’m there, waiting by the bridge with George, and I’m also in that student kitchen, and also on a bus heading to school in Newcastle, holding the book for the first time. My memory tells me that it’s snowing in all three places. I’m distantly surprised when I look up to notice sunshine through the window.

You never need take leave of an author important to you; they’re with you as long as you’re a reader.

There’s a sense in which all readings of a familiar author are rereadings, even the first encounter with a new book. Such occasions are opportunities to re-examine and reassess; they cast new light on old corners, even more so when that first reading is of a final work. Silverview, John le Carré’s 26th and last novel, is about to be published some ten months after his death, and the process by which a copy passed into my hands was satisfyingly covert, involving locked files and passwords; but it also carried a certain sense of trepidation, summed up in four words – what if it’s lousy? It wouldn’t be the first time a book consigned to the bottom drawer bobs to the surface in the wake of its author’s death. What if Silverview was one of these? That the title, with its apparent nod to Bond, seemed out of character for this least Fleming-like of spy writers added to my wariness. I knew I’d rather not read it than witness le Carré’s legacy tarnished by a quick cash-in. But I also knew that I was going to read it regardless.

Which, I did, not in a sitting but in a day, and the first ten minutes dispelled any worries. Silverview fits snugly into le Carré’s late run of novels, and shows the master still giving fresh lessons in tradecraft, lessons younger spy writers would do well to take to heart. It’s about collateral damage, about the effects of Service life on retired and dying spooks and their damaged offspring, a thread to make any reader wish that le Carré had realised his plan of discovering what happened to Karla’s daughter. There are glances into the secret world which startle with their very ordinariness (a photo of the Service’s cricket team, glimpsed hanging on a wall), and – above all – there’s his ongoing examination of the complex algorithms of trust and betrayal, of absolute friendship and utter treachery. ‘There are people we must never betray, whatever the cost,’ one character explains to another. ‘I do not belong in that category.’

When Iain Banks died, his final novel – published in the last days of his life – sat on my shelf unread for years. He’d been a long-time companion, and I wasn’t ready to say goodbye. But, in reality, you never need take leave of an author important to you; they’re with you as long as you’re a reader. Le Carré has gone, but the books are here for good, and Silverview is as fine an addition to his body of work as we could reasonably ask for. A swan song, yes, but no dying fall. Le Carré’s view from the threshold is as clear as ever.

How le Carré wrote feels just right to me; feels like how a spy novel should be written

John le Carré has been important to me almost all my reading life, an importance that has inevitably spilled over into my career as a writer. Whether or not I borrowed J. Lamb from the pages of Smiley’s People, the opening chapter of my Dead Lions is certainly in debt to that book, with one old spook tracing the final movements of another. And the cadences I occasionally adopt as feeling just right for spy fiction betray his influence. "Seasoned Park watchers later said that the affair really began in Fischer’s" reads the opening line of my novella The Drop, and, if I didn’t have a copy of The Honourable Schoolboy propped open at my elbow when I wrote it, I might as well have done: "Afterwards, in the dusty little corners where London’s secret servants drink together, there was argument about where the Dolphin case history should really begin."

I think that’s my point, really: that how le Carré wrote feels just right to me; feels like how a spy novel should be written. The shadow he threw on the genre is matched by the light he cast, and, while there will always be other espionage novelists, the degree to which I admire them depends on how much they invoke the feelings I had on first encountering his work. Those feelings, it turns out, have endured until the final novel, and I’m gladder about this than I can readily describe. So I hope he’d have recognised the occasional borrowed rhythm, and a subliminally pilfered cover name or two, as part of the bridge-building writers do – bridges on which, when conditions allow, exchanges might take place. For, as le Carré’s work has always shown, in dark times walls are built, but bridges are what matter.

This is a revised version of a piece that first appeared in The Times Literary Supplement on 8 November 2019.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

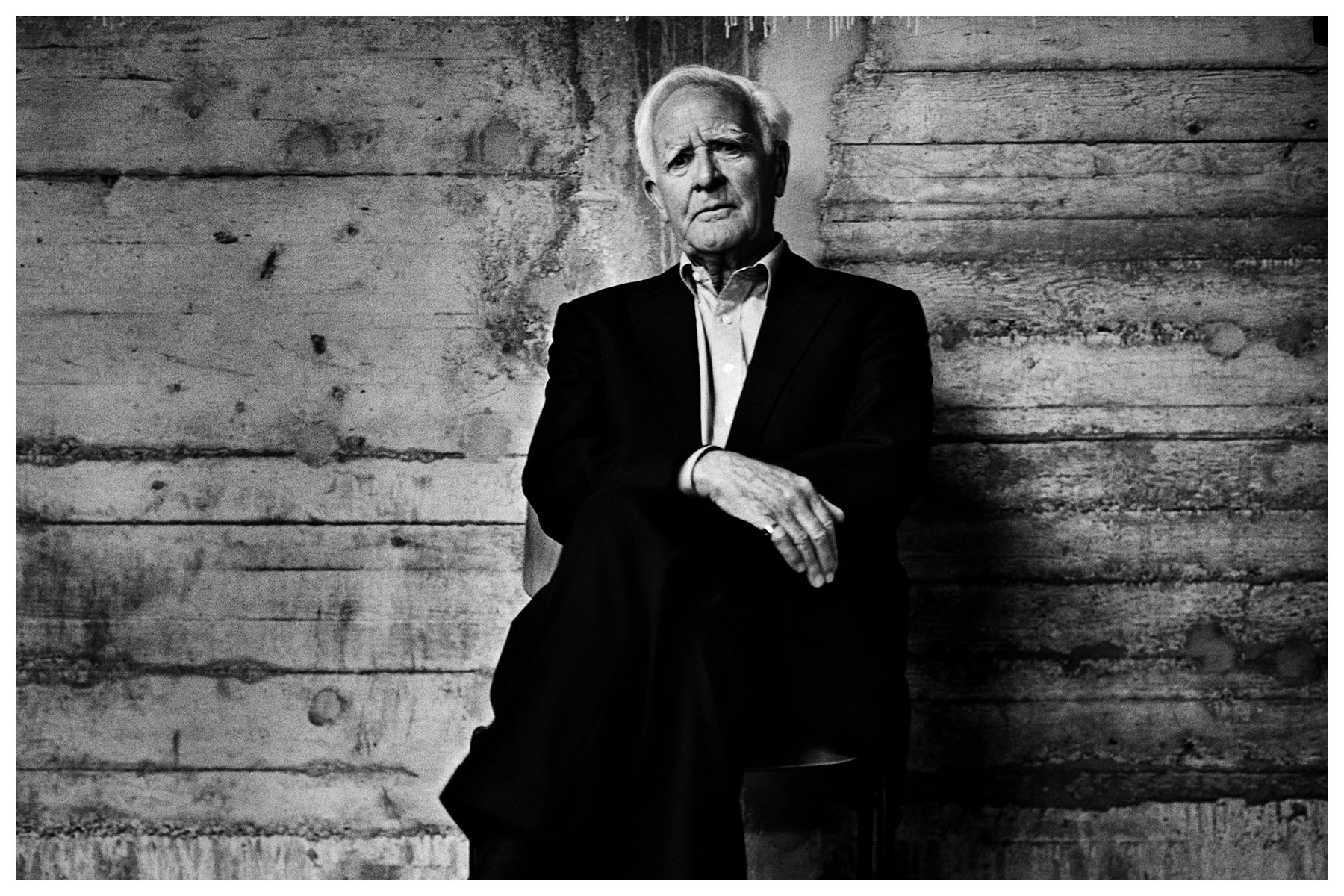

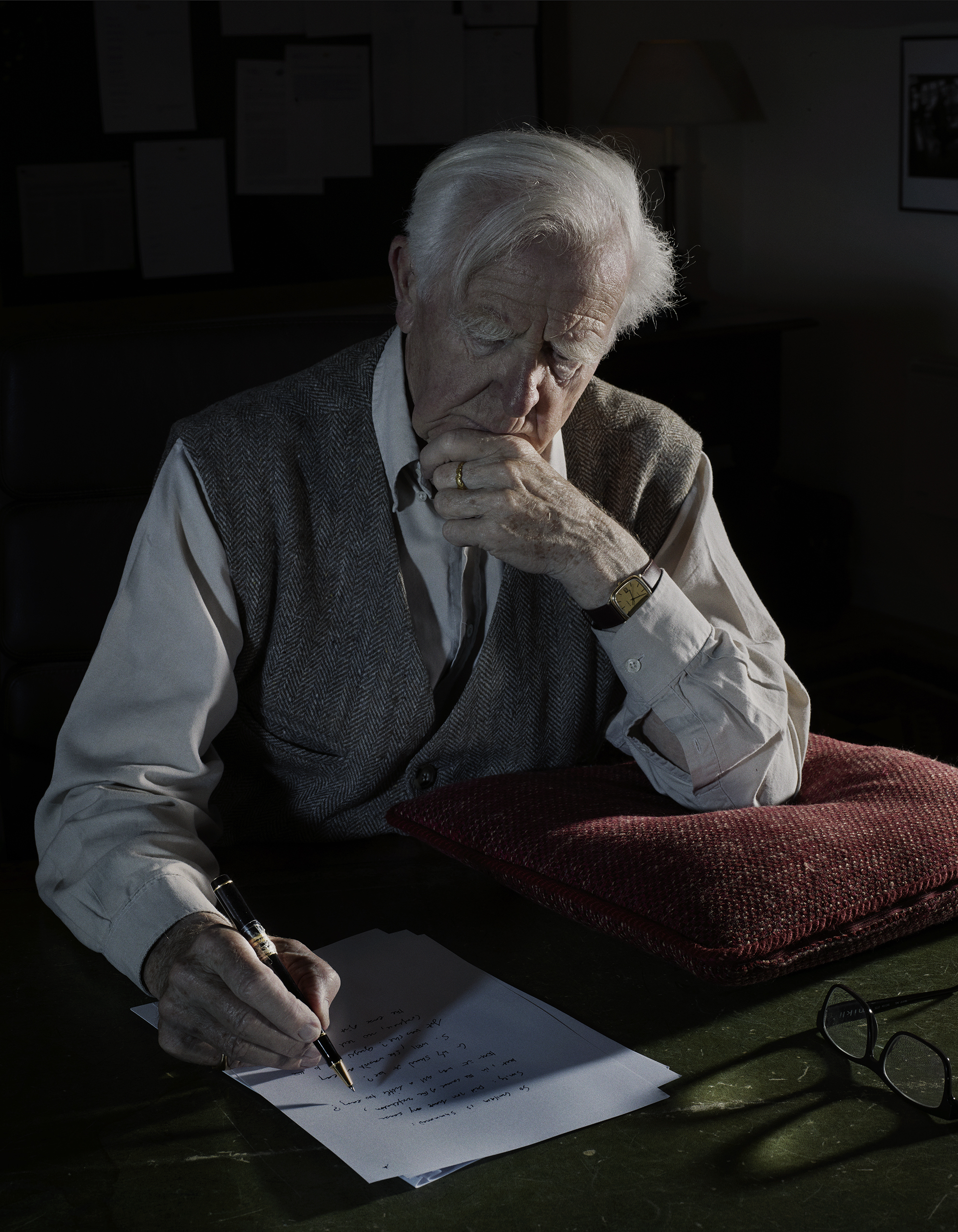

Image: Anton Corbijn