- Home |

- Search Results |

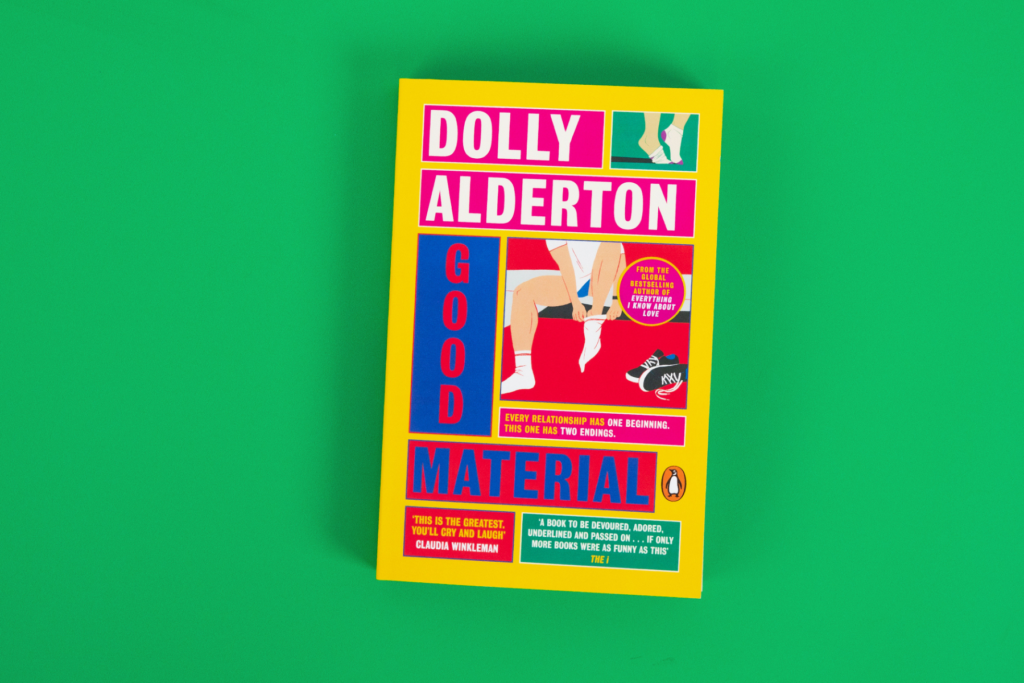

- An Exclusive Extract from Good Material by Dolly Alderton

An exclusive unpublished chapter from Good Material, out now in paperback, eBook and audio.

Friday August 16th

The 9 AM coach from London to Edinburgh takes nine-and-a-half hours, which means I’ll be there with just enough time to see Emery’s show, do a couple of late-night spots, maybe try out some new material, then go drinking afterwards. I wake up at six to fit in a weight-lifting session at the gym and prepare three tupperwares of truly disgusting high-protein, high-fat, low-carb meals and snacks for the journey.

As I board the coach with my backpack optimistically stuffed with four condoms and three Great American Novels, I allow myself to admit that I have wanted this all summer. The misery of taking a show up to Edinburgh is still so fresh in my mind - the exhaustion, the insecurity, the jealousy, the brushes with gout from a month of fried food and excessive alcohol, the financial destitution at the end of it all. The hope that it might have been worth it; that important people may have been watching you and admiring your work, only to come back in September and not have any calls from your agent.

And yet every summer since I stopped going, I’ve hated not being there. It’s as if I can only enjoy the experiences of those Augusts as something firmly in the past - I pursue and cherish them, but only as a mental exercise. I know that if I took a show up next year, the present achievability of that summer would be far less enjoyable than the relationship I would have to the memory of it.

I can only manage fifteen pages of The Grapes of Wrath before I put it on the vacant seat next to me, where it nobly sits for the remaining eight-and-a-half hours of the journey. I swap it out for my favourite book, my phone, and eat through a good portion of the coach ride listening back to all the various funny voice-notes I’ve sent on the boys’ group chat over the last year. I once again observe with interest that it is never other people’s voice-notes I want to relisten to, and only my own. I really have to start that podcast next year.

Halfway through the journey, having looked at every photo on my camera roll right back through the years of B.J. (before Jen), D.J. (during Jen) and A.J. (after Jen), I make a mental album of the photos I would select for a hypothetical dating profile. This leads me to making an actual album, which then leads me to downloading an actual dating app. As I fill in the profile, selecting photos in which I look most tanned and fun and attractive, I luxuriate in the comfort of creating this perfect avatar of myself while sitting on a coach on a motorway, rain thrashing at the windows, eating little roll-ups of sliced ham stuffed with cottage cheese from a tupperware box.

Once the dating profile is completed, with bespoke jokes and factoids about myself, I am notified by my phone that it is at twenty percent battery. There’s still four and a half hours of the journey left and no power sources on the coach, so I download a podcast series about the life and loves of Princess Diana and turn off my cellular data. As the minutes tick by, the red line on my battery icon gets thinner and thinner and I’m filled with increasing dread about my impending solitude. With two hours left to go before we get to Edinburgh, it dies. I have nothing but my brain for company. I stare out at the roads and run through a mental assault course of thoughts, trying so hard to vault over the Jen-related ones. And all of this still feels more enticing than any of the books I’ve packed.

When I get to the coach station, I strap on my rucksack and walk to Emery’s show. When I arrive in the courtyard theatre, his name is at the top of the chalkboard that lists all the shows on at the venue. Emery PHILIPS - BAD MAN, SOLD OUT. At the box office window, I ask to collect my ticket, but am told that he hasn’t put one aside for me. This is typical Emery - promising something whole-heartedly then forgetting to follow through because he got distracted by another thought. I manage to persuade them that I’m his friend and he’s expecting me, and they put me in a seat at the back of the small black room.

Once the dating profile is completed, with bespoke jokes and factoids about myself, I am notified by my phone that it is at twenty percent battery.

The packed audience is full of energy. They’re here for a good Friday night, they’re on his side already. I can hear mutterings of people saying they’ve heard the show is great and even one man says he’s already been earlier this week and enjoyed it so much he’s come back again. The opening thrashing guitar of Too Drunk to Fuck by The Dead Kennedys plays from the speakers. Backstage, Emery introduces himself into a mic. He walks on holding a plastic pint glass of beer, which raises instant, easy cheers from the crowd. He looks untouched by his weeks at the festival. The booze and lack of sleep and lack of exercise hasn’t done anything to him. If anything, he looks more like himself than ever. His pale eyes sparkle in the stage lights, his hair is dishevelled in a way that suggests a good time. He moves his hands and limbs with a tired floppiness that adds to his improvised charm. His enormous grin and angular jaw fill the stage.

He begins with crowd work, chatting to audience members and quickly converting benign answers from them about where they live or what their job is into glittering gems of observation that he seems to effortlessly build into miniature surrealist sketches. I don’t know whether he’s grown more confident in his patter since he’s become the toast of Edinburgh, or whether it’s just luck of the night, the crowd, the individuals. He does ten minutes of this off-the-cuff stuff before he’s even started his scripted show, the title of which is inspired by the last text his ex-girlfriend ever sent him: you are a bad man. What follows are shameful memories from boyhood and adolescence, observations about the complexities of modern masculinity and modern morality. He weaves in stuff about his late father who was never faithful to his mum. He talks about going to a medium to see if the spirit of his dad will ever take responsibility for his actions in the afterlife in the way he couldn’t while he was alive, which begins ludicrously funny and turns into something heart-wrenchingly profound. He is surprisingly clear-eyed and self-aware about his own failings and flaws. He plants tiny seeds of jokes in part one that come into full bloom in the final section, just as you’ve forgotten about them. It’s still characteristically edgy, but he turns his heart inside out when you least expect it.

It’s really, really good.

I stand on the courtyard cobbles, seething at myself, trying to think of the version of that show I would have written, with tired and cliched observations on gender and cowardly confessions from my personal life that aren’t real confessions because I’m too scared to expose myself emotionally. I feel hot and sweaty as I listen to my inner-voice scolding me for simply not being talented enough, a completely unactionable conversation we’ve already had numerous times. I stand outside with two pints in my hand, looking out for Emery, assuming he’ll do that ambling victory lap of the bar that you do in Edinburgh when you’ve just done a phenomenal show.

I remember what that was like.

“ANDY!” a female voice shouts. I turn around and see Thalia, for the first time without her ukulele. I wave at her. She runs over and hugs me as I hold both pint glasses aloft.

“Hello mate!” she says. “How are you! I didn’t realise you had a show up here?”

“I don’t!” I say, so cheerily it borders on defensive. “I did. I used to. For eleven years. But then I stopped. I’m just here for the weekend.”

“Ugh,” she says, taking out a packet of fags from her back-pocket and lighting one. “You made the right choice.”

“How’s it all going?” I ask.

“Terrible. I’m on at a venue on the outskirts of town at eleven in the morning. Performed to a crowd of three today.”

“Ouch,” I say. “We’ve all been there.”

“Listen to you. ‘We’ve all been there’. Didn’t you win newcomer of the year here when you were, like, my age?”

“Yeah but what have you heard of me since?” I say. She smiles, not sure how to respond.

“So, what are your plans while you’re here?” she asks, exhaling a ribbon of smoke into the air.

I feel hot and sweaty as I listen to my inner-voice scolding me for simply not being talented enough.

“I’m staying with Emery,” I say. She grabs my arm as if to steady herself.

“Have you seen his show?”

“Just saw it tonight. So good.”

“Oh my days,” she says dramatically, holding her hand to her head. “Can you believe it? Honestly I laughed and I cried. I never cry. Or laugh, to be fair. Was not expecting that from him.”

“Really good,” I repeat flatly.

“You going to see more shows?”

“Yeah, I’ve got a load on my list,” I say. “And hopefully do a couple of sets.”

“You should do the late cabaret show I’m in tomorrow night! Emery’s done it. It’s really fun. There are always open slots.”

“Wicked, that sounds great. Thanks,” I say, immediately feeling fractionally less of an imposter.

“Oh - there he is!” Thalia says. She points behind me and I see Emery smiling, drink in hand, walking from out into the courtyard, waving at people as he goes. A man comes over and puts his arm around him. Emery says something in his ear and he roars with laughter. He slaps the man’s chest affectionately and tells him he’ll catch him later. We call his name and he sees us.

“ANDY!” he shouts as he walks over, arms outstretched in a way that suggests dismay. “MY DEAREST BOY. I can’t believe you’re here!” He pulls me in for a hug and thumps my back a few times. “This really is the most wonderful surprise.”

“You knew I was coming!” I say in a tone that I try to pass off as casual. “You told me to come!”

“Of course, of course,” he says, wincing in a self-reprimanding way. “You know how it is, August in Edinburgh, different hemisphere up here. Everything gets foggy. How long are you here for?”

“Dunno,” I say. “Until Monday maybe? Maybe Tuesday?”

“You should stay with me and Marcus!”

“I am staying with you and Marcus,” I say, catching Thalia’s embarrassed smirk.

“Oh amazing, amazing, of course you are, yes,” he says. “Great. Marcus will be so pleased. He’s coming a bit later.” He turns to Thalia. “Matthews,” he says sternly. A classic Emery move, to call women by their surname in a way that would sound weird and leery out of the mouth of any other man. Sure enough, it works and she’s smiling at him and putting a cigarette in his mouth. They’ve definitely fucked since they’ve been here.

“ANDY!” he shouts as he walks over, arms outstretched in a way that suggests dismay.

“MY DEAREST BOY. I can’t believe you’re here!”

“This is for you,” I say, handing over the pint.

“Oh thanks man, sorry a guy from the audience bought me one. Came over afterwards to tell me all about his dead dad. Such a nice guy.”

“Have you had a lot of that?” Thalia asks. He nods wearily. I find myself wanting to not say that I’ve just seen his show; wanting to withhold praise from him, as if me not saying how good it is won’t make it good anymore. I hate myself.

“Saw the show,” I finally say when there is a brief pause in flirting between him and Thalia. His eyes widen.

“And?” he asks expectantly.

“Mate, so fucking good,” I say. “Your best work yet.” He puts his hands in prayer.

“From your lips to God’s ears, Andy Dawson,” he says.

“Honestly. You should be so proud of yourself.” He looks genuinely pleased, which I find touching. Thalia says she has to run to another show and she and Emery have a strokey goodbye hug.

“Let’s find a seat!” he exclaims with an even more heightened energy, scanning the benches. I know why this is, he wants me to explain precisely why his show was so brilliant. He wants me to tell him all the bits I liked, then he wants to explain how he came to write and perform all the bits I liked. And of course I’ll do it, because that’s what we do for each other. And because that was me once. I was the person bathing in all the praise and glory. And now it’s my turn to run the bath.

But people keep spotting Emery and interrupting us to tell him how much they loved the show. Some laugh hysterically as they recount the funniest lines to him, some are more earnest, disclosing how the more personal parts of the hour related to their own experience. Whatever they say, he has already perfected the right response. One hand on their shoulder in gratitude, one hand on his heart in humble acceptance of their praise. “God bless you,” says on repeat. “That really does mean the world to me.” To begin with, he does the charitable thing of introducing me as his “friend and fellow comedian” until he realises this is a complete waste of time as they have no interest in registering my existence, let alone talking to me, and instead I get my phone out, realise its dead then put it back in my pocket over and over again.

When Thalia comes straight back to see us after the show, she is a little more overt with her interest in Emery and sits on his lap as she tells us, with great relish, about the terrible stand-up she’s just seen. When she goes to the bar to a round in, I turn to Emery and speak in a hushed voice.

And because that was me once. I was the person bathing in all the praise and glory. And now it’s my turn to run the bath.

“You fucked her, didn’t you?” He shrugs as he lights the cigarette.

“She’s over a decade younger than you,” I hiss.

“Yes, precisely,” he says. “Gen z. They’re a great bunch. Not like our lot, all stressed out about everything. And not like Gen X, droning on about the past. They’re very present, conscious creatures. I basically now only have interest in boomer women, or Gen Z and nothing in between.” At that moment, Marcus comes over. Five-foot-five, point-featured, with a mod haircut and a dead-pan way of speaking, both off-stage and on-stage. He would tell you your mother died in the same tone as informing you the Chinese takeaway has arrived.

“Alright Andy mate, how’s it going?” he says. “What you doing here? Have you got a show on?”

“No, of course I haven’t got a show on. What kind of management do you think I have that I would have had a show on and none of you would know about it or see it promoted anywhere?” I garble. Marcus looks confused. I modulate my voice to meet Marcus’ nonchalance. “Here for the weekend, just a flying visit.”

“Oh cool, man.”

“He’s staying with us, he’s going to crash on our sofa,” Emery says, stubbing out his cigarette.

“Nice one,” he says.

“How you been? How’s it all going?” I ask him.

“Fine. Done eight gigs today,” he says, exhaling with exhaustion. “Ready for a drink.”

“Eight?!” I say.

“Yeah, plus my own show, so nine, technically. Just came from that.”

“Right, I’ll get the next round in,” I say.

“No, you’re alright,” he says, taking out a wodge of notes and coins from his pocket. “Might as well get rid of some of this. Same again?” he asks.

I don’t feel good. My head is pounding, I feel both shivery and hot. I recount what I’ve eaten today - four black coffees, an avocado, the ham and cottage-cheese roll-ups, a pack of dry chicken breast pieces, half a packet of feta, a handful of blueberries, a handful of almonds, a packet of smoked salmon. All above board. Surely professional jealousy can’t make me physically ill?

I manage one more drink before asking Emery and Marcus if I can have the keys to the flat. They walk me to it, as it’s on the way to the next late-night show they’re going to see.

“Are you sure you don’t want to come to Comedian Jelly Wrestling?” Emery asks. “Marcus and I are doing it tonight. Doesn’t start ‘till half midnight.”

“I’d love to,” I say. “But I want to make sure I’m on better form for tomorrow. I’m sure I just need some sleep.”

“Fine. Done eight gigs today,” he says, exhaling with exhaustion. “Ready for a drink.”

“Eight?!” I say.

“Honestly it’s so funny, last week, Emery wrestled this guy-” they both start laughing and are barely able to tell the rest of the anecdote because the mere memory of it has made them breathless with laughter. This goes on for the rest of the walk - the pair of them, delirious from their own in-jokes collected from the festival so far. The night of the rap battle, the silent disco, the story of who ‘Chicken Dave’ is. They let me into the flat and chuck a blanket on the sofa and a folded-up sheet as a makeshift pillow. They say their goodbyes and encourage me to “pop in” to jelly wrestling later. I plug my phone, lie on the sofa as I wait for it to charge and I hear the pair of them laughing and talking all the way down the street, onto their next stop in the wilderness of a weekend. I have an ungenerous thought about whether Emery would live with me if I were in Edinburgh this year, because I’m not currently on the same rung of success that he and Marcus share.

The makeshift pillow is too flat so I use The Grapes of Wrath to bolster it.

Saturday August 17th

I am woken up at five AM to the sound of Emery and Thalia crashing in.

“SHHHH!” Emery shouts.

“I’m awake,” I croak, my throat scratchy, neck stiff, teeth chattering and damp from a fever.

“Mate! You ok?” he slurs with concern, coming towards me and examining me like something found washed-up on a beach.

“Think I’ve got the flu.”

“Oh no, poor baby Andy,” Thalia says, stroking my sweaty hair.

“It’s really fine, you don’t have to-” I say, gently moving my head away from her drunken grasp.

“OK, well let us know if you need anything,” Emery says, grabbing Thalia’s waist and kissing her neck, moving her towards his bedroom. She giggles.

“Thanks,” I say, rolling on my side to face the sofa back.

I’m woken up again a few hours later by a poking sensation in my shin. I flinch and open my eyes. The flat is filled with grey morning light. Marcus stands a few metres away from me, holding a mop the wrong way round.

“Hey man, oh poor you, Em told me you are sick. That’s shit, so sorry.”

“What’s that?” I ask, gesturing at the mop. “Did you just poke me with that?”

“So the thing is dude, you’re obviously more than welcome to stay, obviously definitely stay for the whole weekend. That’s not the problem. But, like, we’re doing a show every night for a month? And we can’t get sick, it would just be a disaster. So just to lessen the chance of contamination, would you mind if you stayed like, local to this area all day?”

“What’s that?” I ask, gesturing at the mop. “Did you just poke me with that?”

“The flat?” I ask, rubbing my sticky tired eyes.

“The sofa,” he replies. “There’s a toilet in the hallway, if you use that when you need to, and don’t use the main bathroom, that would be great. I’ve left a mug and cutlery and a plate here.” He points at the arrangement of items he’s left on the floor. “You can order any medicine and food from the local…amenities online,” he says enthusiastically. I nod. I just want him to go away. “Thanks man and hey, call us if you take a turn for the worse or anything, yeah?” I nod again and he puts on his vintage mod jacket and leaves.

Sunday August 18th

Treat myself to a train home rather than the coach. Shaves three hours off the journey. I leave before anyone’s woken up, without a shower on Marcus’ conditions, and leave a note for them both thanking them for letting me crash and apologising for being ill and absent from the weekend. On the way out, I notice a Fringe Festival brochure on the sideboard and, for some reason, take it with me.

When I get on the train, I torture myself with a retrospective round best version/worst version of the weekend I’ve just had. I open the festival brochure and circle all the shows I would have seen. I get out my notebook and write an itinerary, imagining myself going from sketch show to improv show to my favourite stand-up shows. I use the map on my phone to track how long I’d have in between each of them, plotting pub stops along the way. I send a text to a comedian friend who hosts a fun, rowdy mixed-bill every night that pulls in a big crowd of festival goers and Edinburgh locals.

Hey dude! How are you? I’m in Edinburgh!

Off-chance: do you have a spot for me tonight?

The one thing that brings me a distant sense of comfort is the stand-up hour that I wanted to see the most over the weekend would most likely have been sold out last night anyway. So even if I had been well, I wouldn’t have missed out on it. The number for the Fringe Festival Box Office shines off the page in bright yellow. Can I do this? Am I going to do this? I thought I already knew the limits of my pettiness but maybe I was wrong?

“Hello, Fringe Festival Box Office, how can I help?” a bright and cheery male Scottish voice answers.

“Hello, this is a bit of a strange request, but I wanted to know if the 8 o’clock show at The Assembly Hall was sold out last night or whether you released some tickets on the door?” There’s a pause.

“Sorry, so is that tonight, you’re wanting to go? To the 8 o’clock show?”

“No, last night, is when I’m inquiring about. For tickets. One ticket, please,” I say, lowering my voice and looking at the train floor.

“Last night?”

“Yes, August 17th, Saturday night. The night just gone.”

“But…that’s in the past. You can’t buy a ticket for the past.”

“Alright, Nietzsche!” I laugh. There is quiet on the other end of the phone.

“Is that the name of another show you’d like to see?” he asks.

“Don’t worry,” I say. “Thank you for your help.”

I hang up and see a reply from my friend.

Hey Andy! We’d love to have you!

I’ll put you on third, does that work?

I consult my notebook. It would have worked perfectly. Then I would have got the coach back tomorrow morning and be home in time for dinner. Full of new experiences and stories. Maybe some TV producers or big agents would have seen me perform, which could have opened up some proper work opportunities. I might have had a passionate two-day fling with a hot leafleter who I met in passing on The Royal Mile. The best version of the weekend is complete. I text him back to apologise and say on second thoughts I’m not going to be free after all, but thanks for finding me a slot and I’ll catch him back on the circuit when Edinburgh’s done.

“But…that’s in the past. You can’t buy a ticket for the past.”

My head heavy with flu, I enjoy a fifteen-minute upright nap in the train toilet, with my head against the cold steel sink. When I return to my seat, the woman behind me is curled up like a cat across the row. Eyes shut, legs tucked into her chest, white plimsolls hanging into the aisle. I have an inexplicable urge to know this person; to sit next to her and have her head rest on my shoulder. I wish she was mine to worry about. I miss worrying about someone. I miss someone’s neck pain from a nap on a train seat being my concern. I want to know about someone’s meeting tomorrow morning. I want to know about someone’s mum’s knee operation. I want to know what someone’s favourite thing on the takeaway menu is. I want them to know about my flu and my failed weekend in Edinburgh. I want them to buy me some painkillers and I want to run them a bath. I want to know a phone number off by heart. I want to know what time their plane lands. I want them to know what time my train’s getting in. I want to feel like someone belongs to me and I belong to them.

When I get to the station, I expect her to be there, like she was that first summer we met when I returned from Edinburgh. She stood on the platform in her sandals and flowery dress and denim jacket and waved when she saw me through the crowd. I don’t know why I expect her to be there again. I scan all the faces, looking for her, but she isn’t there. She doesn’t know what time my train arrives in London. She doesn’t even know that I’ve been away. I don’t know where she is or what she’s doing. Because we don’t belong to each other anymore.