- Home |

- Search Results |

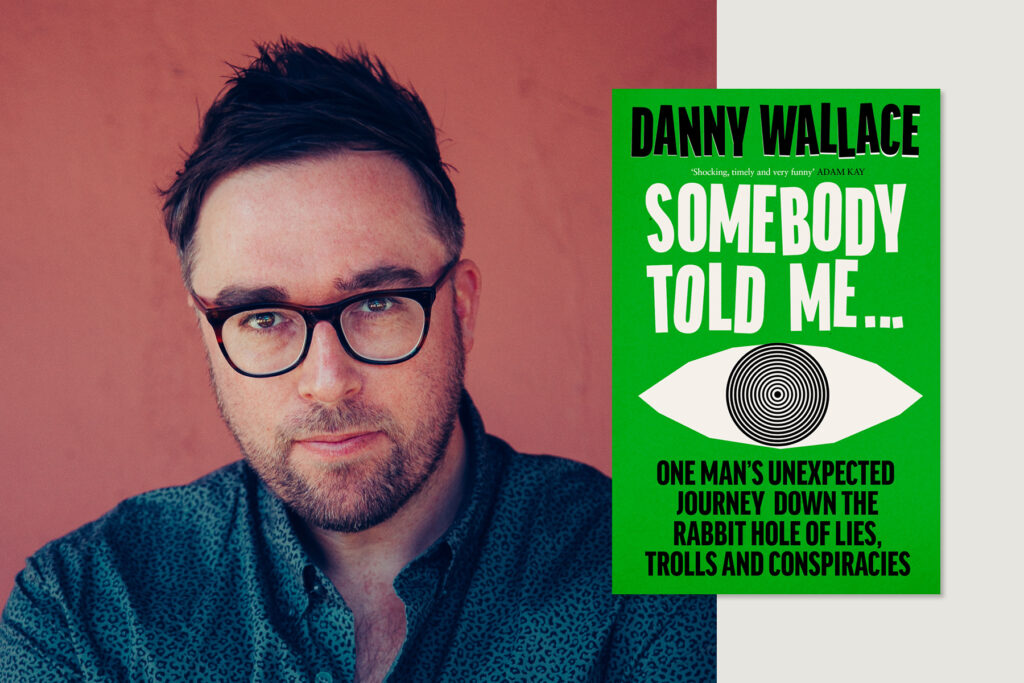

- How to spot disinformation online – and avoid spreading it

We live in a time when anyone – your neighbour, your brother, you, me – can easily become confused, consume lies disguised as the truth, or become a conspiracy theorist. What can we do to stop this?

I tried to answer this question in my new book, Somebody Told Me. I researched the past few years of disinformation, falling down the rabbit hole into a world of lies, conspiracies, trolls and grifters.

I’ve learned that lies are powerful. Focused, organised, well-funded campaigns of falsehoods have the power to change the course of entire nations. Not only can they change minds and raise suspicions, but they can influence referenda and elections.

With the General Election around the corner, it’s more important than ever to keep your eyes peeled for disinformation and online lies. So, I’ve put together the following guide for what to look out for when you’re online…

Beware of professional trolls

For a long time, anyone who blamed strange messages they received online on “Russian bots” or “troll factories” was looked upon with pity. It seemed too fanciful, this idea of huge rooms, filled with screens, packed with people pumping out random bile at innocent civilians.

Yet we now know that there are indeed huge rooms, filled with screens, packed with people pumping out random bile at innocent civilians.

'Don't even block them, because even that tells them something about how to irk you'

Often their work is not to convince us of one thing or another in particular. It’s simply to sow discord and division. Start a fight. Or make you give up arguing your point of view, wearied by constant rebuttals.

Or it can be to convince you that you are in the minority; that there is a huge groundswell of ordinary people who think you are wrong. To make you feel you are outnumbered and unprepared. In both cases, the idea is the same: to exhaust you.

So: don’t engage. Don’t reply. That’s what they thrive on: hooking you in, getting your clicks, proving to their boss their techniques are working. Don’t even block them, because even that tells them something about how to irk you. Just mute, whistle a happy tune, and enjoy a more sensible timeline.

They don’t care. It’s literally just a job to them. They’ll have forgotten you in five minutes.

Don’t take images and videos at face value

Do you remember that photo of the Pope wearing a Puffer jacket? That was weird, wasn’t it? We all scrolled through, stopped for a second to see the Pope wearing a Puffer jacket, and thought “wow, the Pope is out here and thriving.”

And then, a day or two later it emerged that the picture was fake. The Pope wasn’t wearing a Puffer jacket, any more than Rishi Sunak was giving out Fortnite tips to Year 8s on TikTok the other day (this viral video was courtesy of AI).

It’s those moments that are going to become more commonplace. The low-level, why-would-they-make-it-up? believable lies that will slowly get bigger and more convincing.

We have to learn to pause for a second when we see these moments, and ask ourselves if it actually seems likely. It’s what I call “the Pope in a Puffer Jacket” rule, and it should really be a law.

Analyse sources – especially new platforms

During this election period, expect to find many more ‘local’ papers springing up online. They’ll be shoved through your door, too, but the online ones are easiest to spot.

'The low-level, believable lies will slowly get bigger and more convincing'

Let’s say you live in Doncaster. Soon you may notice a Doncaster Guardian online. Or a Doncaster Bugle. Or a Doncaster Trumpet, when you have never before heard of any of them.

It will carry local news (probably nicked from real Doncaster papers or AI-generated) but may also feature columns or talking points which favour one side of a debate or another.

Or the news will be angled a certain way to make you feel annoyance at a specific group of people (maybe migrants? Nurses? Remainers?).

Ask yourself: where did this ‘newspaper’ come from and who is behind it? Do I recognise any of the names? Are these real journalists? Who registered the website? Where did it appear?

Quietly question it – and don’t share it. Let it wither on the vine.

Sharing’s not caring

And on that note – a little more on the world of sharing. Disinformation thrives not just on our belief, but on our engagement.

During heightened political times, when there is more argument and debate, there is often a human need to demonstrate we are on the right side of history. We will see something online – some terrible opinion or other written by some absolute drainpipe – and we will retweet or reshare it with our own opinion tacked on. “Disagree!” or “Look at this ninny!” or whatever.

'Just by doing nothing, you have done something'

It’s to show we don’t agree with it, that we’re better than it – but we’re falling into a trap. We’re broadening its audience to make ourselves feel better, and the problem is, it will find (even for those of you with the nicest followers in the world) someone else who agrees with it. Don’t put them together. Don’t think you’re being clever by screenshotting it and sharing it that way.

Just take a deep breath, suck it up, and know that just by doing nothing, you have done something.