- Home |

- Search Results |

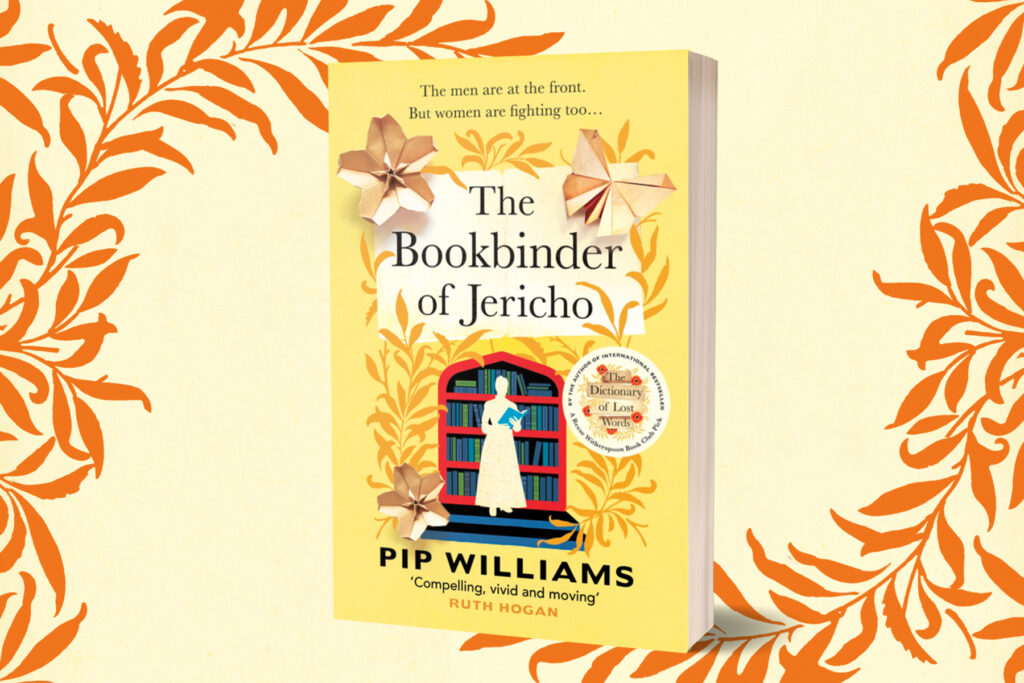

- Extract: The Bookbinder of Jericho by Pip Williams

Extract: The Bookbinder of Jericho by Pip Williams

Peek inside the bookbindery at Oxford University Press in the new novel by the internationally bestselling author of The Dictionary of Lost Words.

Scraps. That’s all I got. Fragments that made no sense without the words before or the words after.

We were folding The Complete Works of William Shakespeare and I’d scanned the first page of the editor’s preface a hundred times. The last line on the page rang in my mind, incomplete and teasing. I have only ventured to deviate where it seemed to me that . . .

Ventured to deviate. My eye caught the phrase each time I folded a section.

Where it seemed to me that . . .

That what? I thought. Then I’d start on another sheet.

First fold: The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Second fold: Edited by WJ Craig. Third fold: ventured to bloody deviate.

My hand hovered as I read that last line and tried to guess at the rest.

WJ Craig changed Shakespeare, I thought. Where it seemed to him that . . .

I grew desperate to know.

I glanced around the bindery, along the folding bench piled with quires of sheets and folded sections. I looked at Maude.

The only thing that could upset the applecart at that moment was me

She couldn’t care less about the words on the page. I could hear her humming a little tune, each fold marking time like the second hand of a clock. Folding was her favourite job, and she could fold better than anyone, but that didn’t stop mistakes. Folding tangents, Ma used to call them. Folds of her own design and purpose. From the corner of my eye, I’d sense a change in rhythm. It was easy enough to reach over, stay her hand. She understood. She wasn’t simple, despite what people thought. And if I missed the signs? Well, a section ruined. It could happen to any of us with the slip of a bonefolder. But we’d notice. We’d put the damaged section aside. My sister never did. And so I had to.

Keep an eye.

Watch over.

Deep breath.

Dear Maude. I love you, I really do. But sometimes . . . This is how my mind ran.

Already I could see a folded section in Maude’s pile that didn’t sit square. I’d remove it later. She wouldn’t know, and neither would Mrs Hogg. There’d be no need for tutting.

The only thing that could upset the applecart at that moment was me.

If I didn’t find out why WJ Craig had changed Shakespeare, I thought I might scream. I raised my hand.

‘Yes, Miss Jones?’

‘Lavatory, Mrs Hogg.’

She nodded.

I finished the fold I’d started and waited for Mrs Hogg to drift away. Mrs Hogg, the freckly frog. Maude had said it out loud once and I’d never been forgiven. She had no trouble telling us apart, but as far as Mrs Hogg was concerned, Maude and I were one and the same.

‘Back in a mo, Maudie.’

‘Back in a mo,’ she said.

Lou was folding the second section. As I passed behind her chair, I leant over her shoulder. ‘Can you stop for a second?’ I said.

‘I thought you were desperate for the lav.’

‘Of course not. I just need to know what it says.’

She paused long enough for me to read the end of the sentence. I added it to what I knew and whispered it to myself: ‘I have only ventured to deviate where it seemed to me that the carelessness of either copyist or printer deprived a word or sentence wholly of meaning.’

‘Can I keep folding now, Peggy?’ Lou asked.

‘Yes, you can, Louise,’ said Mrs Hogg.

Lou blushed and gave me a look.

‘Miss Jones . . .’

Mrs Hogg had been at school with Ma and she’d known me since Maude and I were newborns. Still, Miss Jones. The emphasis on Ma’s maiden name, just in case anyone in the bindery had forgotten her disgrace.

‘Your job is to bind the books, not read them . . .’

Your job is to bind the books, not read them

She kept talking but I stopped listening. I’d heard it a hundred times. The sheets were there to be folded not read, the sections gathered not read, the text blocks sewn not read – and for the hundredth time I thought that reading the pages was the only thing that made the rest tolerable. I have only ventured to deviate where it seemed to me that the carelessness of either copyist or printer deprived a word or sentence wholly of meaning.

Mrs Hogg raised her finger, and I wondered what response I had failed to give. She was going red in the face, the way she invariably did. Then our forewoman interrupted.

‘Peggy, as you are up, I wonder if you could run an errand for me?’ Mrs Stoddard turned a smile on the floor supervisor. ‘I’m sure you can spare her for ten minutes, Mrs Hogg?’

Freckly frog nodded and continued down the line of girls without another glance at me. I looked towards my sister.

‘Maude will be fine,’ said Mrs Stoddard.

We walked the length of the bindery, and Mrs Stoddard stopped occasionally to encourage one of the younger girls or to advise on posture if she saw someone slouching. When we got to her office, she picked up a book, newly bound, lettered in gold so shiny it looked wet.

The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250–1900. We printed it almost every year.

‘Has no one written a poem since 1900?’ I asked.

Mrs Stoddard suppressed a smile. ‘The Controller will want to see how the latest print run has turned out.’ She handed me the book. ‘The walk to his office should relieve your boredom.’

I held the book to my nose: clean leather and the fading scent of ink and glue. I never tired of it. It was the freshly minted smell of a new idea, an old story, a disturbing rhyme. I knew it would be gone from that book within a month, so I inhaled, as if I might absorb whatever was printed on the pages within.

I walked back slowly between two long rows of benches piled with flat printed sheets and folded sections. Women and girls were bent to the task of transforming one to the other, and I had been given a moment’s reprieve. I started to open the book when a freckly hand covered mine and pushed the book shut.

‘It won’t do to have the spine creased,’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘Not by the likes of you, Miss Jones.’