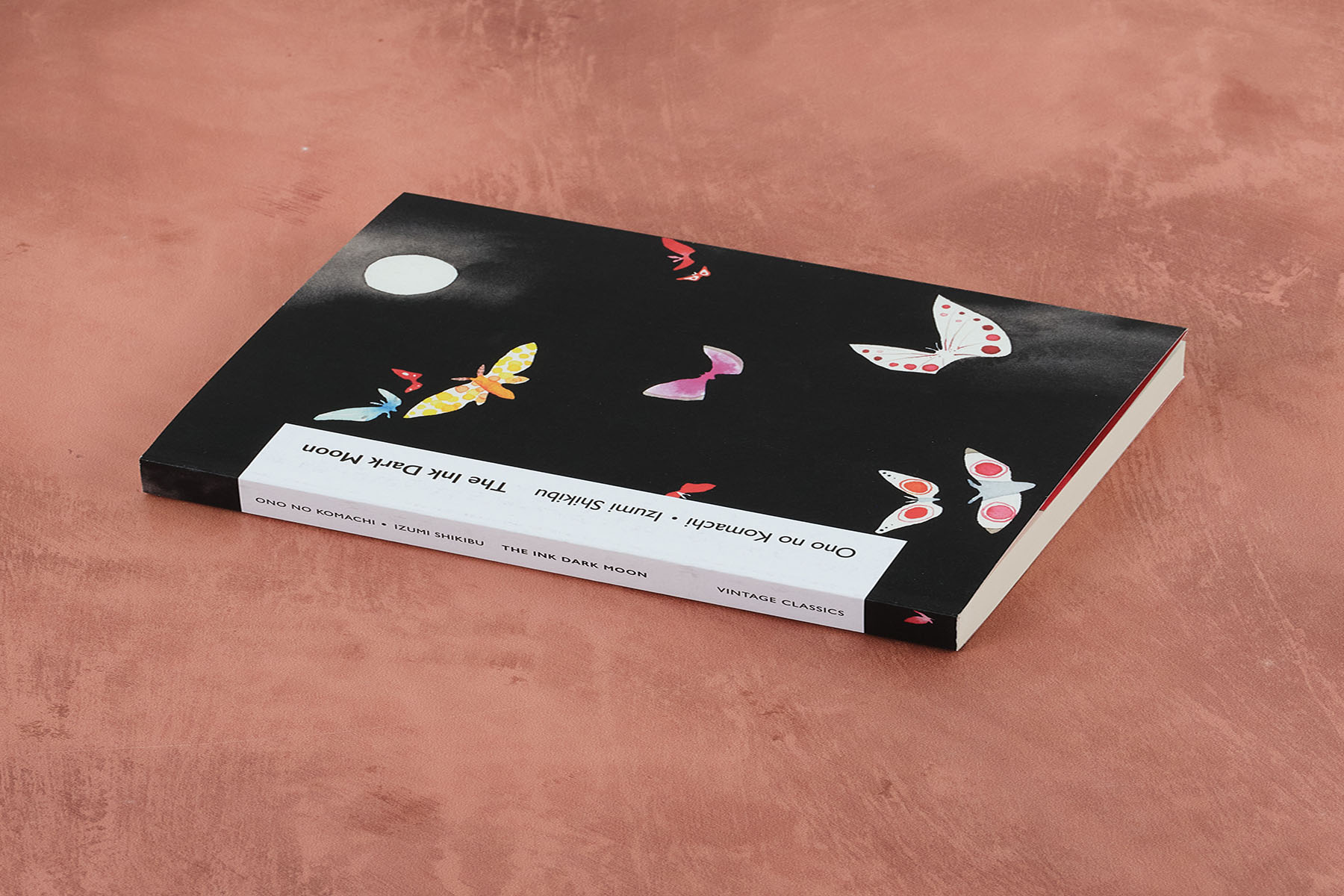

One of three books in the new Vintage Classics Love Poems series, The Ink Dark Moon, composed by Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu, contains sensual, heartbreaking and romantic poetry that was composed during the Heian period in Japan. (The collection also features the revitalisation of Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, both similarly featuring new introductions by contemporary poets.)

Translated by Jane Hirshfield and Mariko Aratani, this edition of The Ink Dark Moon brings the story of the poems to life, and it's enhanced by a tender and insightful introduction by Nikita Gill. Read the whole thing below.

Introduction

A long time ago, my great-grandmother told me that poetry was the language of love, of both the joyful and the broken heart. She told me over a cup of tea on a misty morning that poems are where love can exist in its truest form. Poems never judge love for being too passionate, too despondent or too wistful. In fact, poems say ‘give in’ to the intensity and let your feelings dance across the page. I think this is why, across countless cultures and languages, the love poem remains evergreen, an immortal jewel untouched by the weathering of time.

Although written in the ninth and tenth centuries, the words in The Ink Dark Moon speak powerfully to me, illustrating without a doubt that poetry is the language of love, and like love, stands the test of time. I often say that poetry is an ancient artform that is in the habit of reinventing itself in the hands and minds of the poets of any era. What I have learned after reading this book is that some poems stand the test of time and give something new to each new generation that reads them. My great-grandmother once said that she wrote poems because it was an act of courage and hope to put pen to paper and write vulnerably. Ceaselessly, these poems say that love is courage and hope, but also longing and loss. That where grief exists, so does life, and that beauty can be found in the heart of tragedy. They speak with a yearning and passion that everyone who has ever been in love can recognise. This is the very same vulnerability my great-grandmother so deeply treasured.

This vulnerability is clear from the very first page, where Ono no Komachi takes us into the dreamscapes of longing, her poems capturing the restlessness of unrequited love. My great-grandmother once told me that the tragedy of loving someone who does not love you back, or who cannot love, is as painful a condition as the heart can endure while still beating; these poems capture this with devastating brevity. Anyone who has ever been through such an ache will identify with the words:

Night deepens

with the sound

of a calling deer,

and I hear

my own one-sided love.

But not all of it is about ache, as not all of love is about tragedy. So much of love holds joy. A gentle playfulness lives in Ono no Komachi’s poems which made me smile: there is a poem here about morning glories and another about the flower of forgetting that I recommend everyone reads to truly experience her wondrous wit.

I think humour in poetry – the capacity to make the reader smile or even laugh – is a difficult art to master. Too much and the levity can take away from the poem; too little and it escapes the reader. These poems are able to master humour with precision in just thirty-one syllables without losing the weight of the verse.

The tanka form looks deceptively simple. It is not, and not only because it adheres to a tight format. Every syllable counts and to draw rich images, rhythm and meaning, all within thirty-one syllables, is a hard job for even the more proficient of poets. The translators show Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu crafting it effortlessly.

Where Ono no Komachi’s poems blend the playful with longing, Izumi Shikibu’s work brings the complexity and devastation of grief after losing a good love. There is a specific kind of haunting in her poems – a feeling that sometimes you can sense the ghost of a love long gone within the verses. A poem that I think of often when remembering love lost is this:

Why haven’t I

thought of it before?

This body,

remembering yours,

is the keepsake you left.

Balancing out the heaviness of grief in these poems is a series of sprightly response poems that reveal a lively, sharp intellect. I found myself chuckling at one in particular which was sent to (presumably) a lover who had left their purple robe behind! The boldness here is reflective

of a more modern poetry, a poetry I have seen performed on stages and on social media.

At the heart of this collection are women who are passionately and deeply in love with life as much as they are with the lovers they speak of through these pages. They have a razor-sharp wit and a keen sense of radical observation, rebuking any stereotype of submissiveness placed upon women from antiquity. Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu were celebrated in their time and their work is legendary for good reason.

I wish I could have given my great-grandmother this book. It would have confirmed for her that her belief was true: love and poetry are synonymous. She would have treasured this collection, but beyond that, she would have admired the work of these legendary women who walked many hundreds of years before her.

It is a blessing, then, to have read a book where the voices of two foremothers within poetry are so strong and the poems so breathtaking. Poems which show us so clearly that love knows its favoured language is poetry.

I am so glad this book exists.

And when you read it, you will be too.