- Home |

- Search Results |

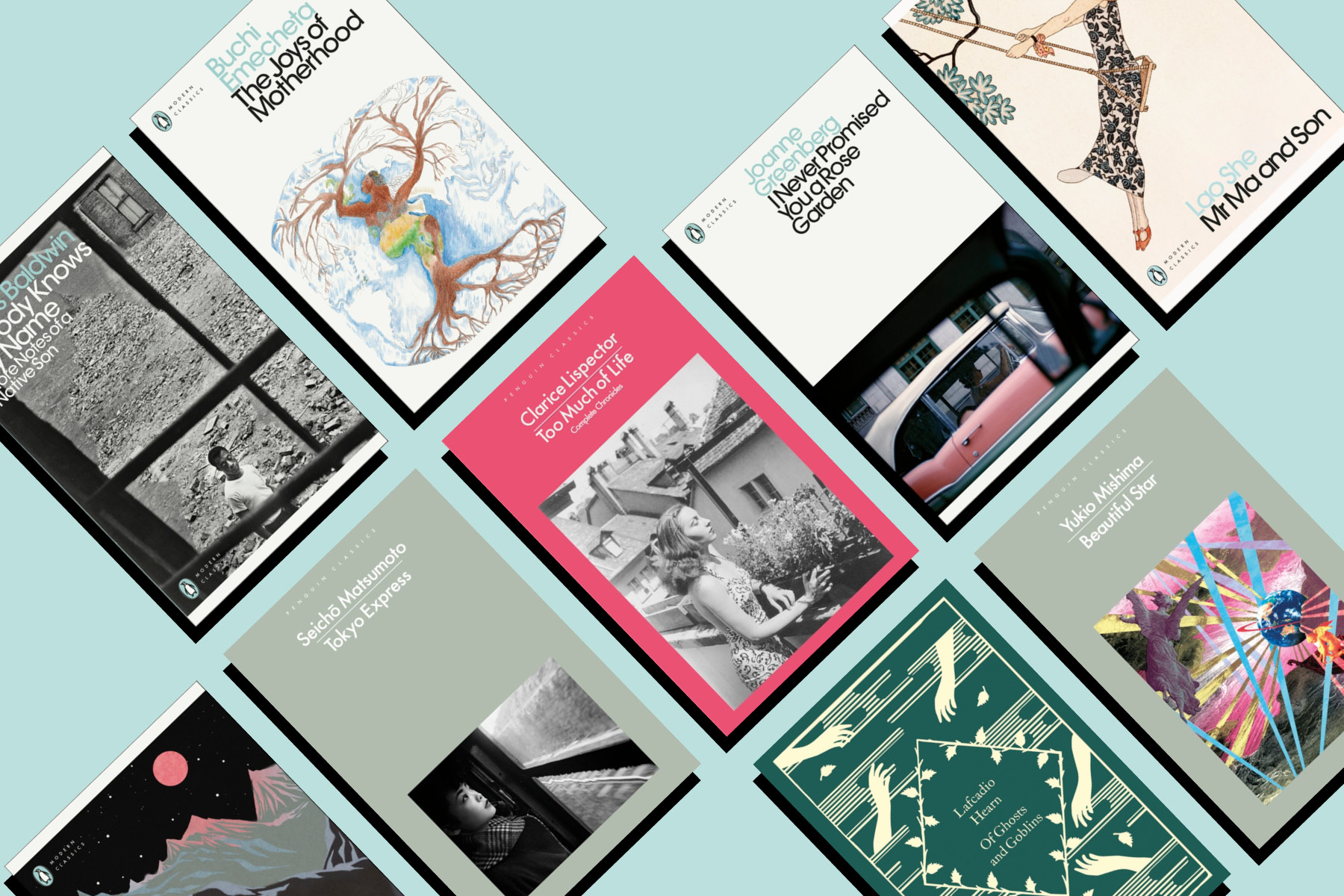

- Off-the-beaten-track classics to broaden your bookshelf

Looking for your next great classic? Re-discover some of these quietly brilliant books and authors, as chosen by Penguin Classics editors. From Japanese ghost stories to the chronicles of one of Brazil’s best writers to a travelogue from Togo to Greenland – all these books are new to the Penguin Classics list this year by writers who have experienced life in all of its devastating beauty.

Too Much of Life by Clarice Lispector (2022)

Clarice Lispector, the patron saint of Brazilian writing, and one of the hidden geniuses of the 20th century, wrote these dispatches from her desk in Rio for the Jornal do Brasil from 1967 to 1977. In doing so, she made the nation fall in love with her. It’s hard to overstate the reverence Brazilians have for Lispector, and these Chronicles are where many first met her. Today, they still provide a thrilling route through which to begin reading her work. These weekly missives manage to straddle the intimate and metaphysical, playful and reverent, flirtatious and serious. Whether considering the question of free will or the lost loves of a taxi driver, the new artists and ideas of the Sixties and Seventies or the foibles of a friend, the Chronicles are tiny, delightful revelations.

This is a book to savour, to dip into, to read a short something that makes you sit up and think. As Lispector herself puts it: “How did I so unwittingly transform the joy of living into the great luxury of being alive?” The wonderful thing about these Collected Chronicles is that they prompt the reader to pay more attention to the great luxuries of our own lives, to attend to the small mysteries and joys all around us, as Lispector does so masterfully.

Chosen by Maria Bedford, Commissioning Editor

Beautiful Star by Yukio Mishima (1962)

Mishima was one of the great Japanese writers, and loved to experiment with different genres. Beautiful Star is science fiction and had been unfairly overlooked for decades as a result, to the extent that the first translation into English only appeared in April.

This novel tells the story of the Osugi family, who have realised that each of them hails from a different planet: father from Mars, mother from Jupiter, son from Mercury and daughter from Venus. Already seen as oddballs in their small Japanese town in the 1960s, this extra-terrestrial knowledge brings them closer together; they climb mountains to wait for UFOs, study at home together and regard their human neighbours with a kindly benevolence.

But father, Juichiro, is worried about the bomb. He writes letters to Khrushchev, trying to warn everyone he can of the terrible threat. After all, humans may be terribly flawed, but aren't they worth saving? He sends out a coded message in the newspaper to find other aliens. But there are other extra-terrestrials out there – ones who do not look so kindly on the flaws and foibles of humans – and conflict ensues, both without and within the family.

At the time of writing the Cold War was in full swing, and questions of human annihilation were very much in the air. Mishima uses this story to ask some big questions: what to make of a species that develops technology like the atomic bomb? Is humanity deserving of redemption? But it’s also a touching, darkly funny story about family, nuclear war, love and UFOs, for everyone interested in any and all of those themes.

MB

Mr Ma and Son by Lao She (1929)

In this effervescent satire of London’s Jazz Age, seen through the eyes of a pair of Chinese immigrants, no-one escapes the punishment and playfulness of Lao She’s pen portraits. The fastidious landlady Mrs Wedderburn, delicate as an ornamental shepherdess, and her boorish flapper daughter, both get it in the ribs; but frankly, Lao She isn’t any less funny about mandarin-obsessed stick-in-the-mud Mr Ma or his romantic, ambitious son Ma Wei. Crammed with hilarious observations, interludes of silliness and the most embarrassing piece of embroidery ever to grace a hat, Mr Ma and Son is also a mournful novel about unrequited love and the cost of prejudice.

Chosen by Ka Bradley, Commissioning Editor

Hell Screen by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1918)

Regarded as the father of the Japanese short story, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa is probably best-known for inspiring Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashōmon (both stories that the film is based on are included in this haunting collection). But his taste for the absurd, his exquisite knife-blade handling of horror, and his architectural eye for a story’s structure make him one of the towering masters of the form. And as ruthless as he was with his characters, he spared nothing of himself – as the autobiographical fragments in ‘The Life of a Stupid Man’ devastatingly demonstrate.

KB

Joanne Greenberg’s semi-autobiographical novel often draws comparisons to Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. The touchstones are there: a witty, intelligent young woman protagonist with a creative bent; bone-achingly vivid descriptions of psychiatric treatment; lavish, lyrical writing around pain, daughterhood and dissociation. But Greenberg’s masterwork is also remarkable because it is such a hopeful story. In Rose Garden, a young woman learns to live with schizophrenia with the support of a psychiatrist who trusts and believes her. Its message – that the battle against mental illness is made possible through engaged medical and community care – is as important now as it was in 1964.

KB

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929)

Nella Larsen’s Passing is like a flowering tea bud. It is a taut, compact, compelling novella that follows Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry – two light-skinned Black women who can 'pass' for white. On a first read, the sheer propulsive force of Larsen’s storytelling carries the reader swiftly to its tragic, devastating conclusion. But with every re-read, the complex themes of Passing open up like a tea bud under hot water. I’ve never come away from the book without wondering where my thoughts should be turned – to Clare? to Irene? – and Larsen’s precise, impactful prose, flexing along every line, means my footing is always unsure (as it should be – there is no ‘moral’ to Passing, only a strong sense of compassion and exploration). Often described as a novel about race, Passing is also a novel about desire, gender, class, belonging and jealousy. To layer so many petals of meaning into one slim book is an utterly virtuoso act. I know if I re-read it again, and tried to rewrite this recommendation, I’d bring an entire other facet to it.

KB

Of Ghosts and Goblins by Lafcadio Hearn (1904)

Lafcadio Hearn believed in ghosts. As a child in 19th-century Ireland, abandoned by his mother, his father and then his guardian, he was particularly attuned to the eerie and uncanny; as an adult living all over the world, he sensed spirits in every shadow. It was in Japan, the country he would come to call home, that his lifelong interest in folktales reached its highest pitch. He loved ghost stories most of all: his wife, Setsuko Koizumi, would seek them out from second-hand bookshops and read them aloud at night, the wick of the candle burning low, while Lafcadio, pale and trembling, listened and took detailed notes. In this way the couple translated, conserved and retold in their own voice hundreds of tales from the Japanese folk tradition, the spookiest and the strangest of which are collected here in Of Ghosts and Goblins.

Prepare to find yourself haunted: I vividly remember my first encounter with the mujina, a faceless creature that roams quiet places. I was travelling home late, the only passenger on the night bus, when I read Hearn’s version of the tale. When I finished, my nerves on edge, I looked down the aisle towards the driver’s cab – perhaps it was a trick of the light (I’ll never be sure), but for one terrible moment I could swear his face was as smooth and featureless as an egg. To this day, I find ‘Mujina’ the scariest story in the book.

Chosen by Sam Fulton, Assistant Editor

The Joys of Motherhood by Buchi Emecheta (1979)

Buchi Emecheta was a writer ahead of her time, and her exceptional talent has inspired authors such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Bernardine Evaristo. The Joys of Motherhood is Emecheta’s masterpiece: utterly absorbing, beautifully crafted and carefully observed. The novel follows Nnu Ego from her childhood in rural Nigeria, through the disappointments of her first marriage and on to Lagos where she eventually settles and raises a family, charting her personal trials and breakthroughs against the backdrop of the profound changes of the mid-20th Century. I love the way Emecheta combines a gripping narrative and larger-than-life characters with subtler cultural critique, deep irony and a clever sense of humour – it is the perfect novel.

Chosen by Josephine Greywoode, Publishing Director

Michel the Giant by Tété-Michel Kpomassie (1977)

While reading Tété-Michel’s travelogue, I had to keep reminding myself that it was a true story: a young man runs away from his village in rural Togo in the 1950s and spends eight years making his way to Greenland in search of the land of snow and ice that he had glimpsed in a book. When I met the author, I began to understand the irrepressible spirit and sense of wonder that inspired and sustained this ambitious journey: only someone so incredibly gracious and determined could complete such an odyssey.

Beyond the evocative descriptions and thrill of adventure, his story says so much about what it means to belong: when he arrived in Greenland, Tété-Michel discovered a profound connection with the local people and cultural similarities with his homeland despite the geographical differences. This spellbinding account brings a fresh, illuminating perspective to a genre that had previously been defined by the colonial gaze.

Tokyo Express by Seicho Matsumoto (1958)

It’s easy to see why Tokyo Express is one of the best-selling books of all time in its native Japan: it really is a perfectly plotted and fiendishly twisting detective story. When a young and beautiful couple are found dead on a windswept beach, two detectives set out unpick the knot of this unique and calculated crime. Their journey will lead them first to the arcane ways of the railway tracks that criss-cross Japan – and finally into the coils of a far-reaching criminal conspiracy theory.