- Home |

- Search Results |

- For author Gabrielle Zevin, books are a game

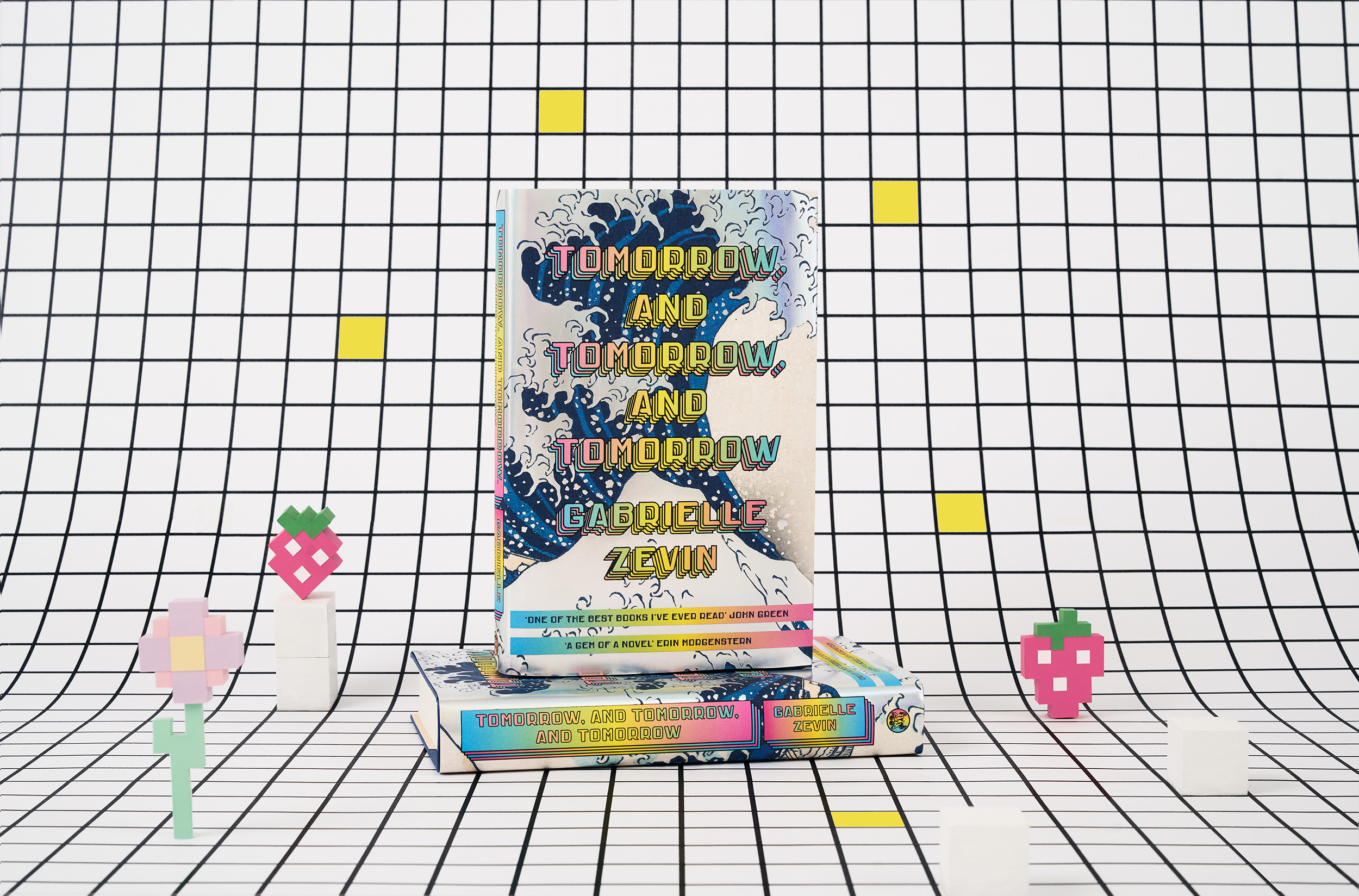

When Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin’s gorgeous new novel, debuted in The New York Times’ bestseller list, the author said the best part was that it did so at number three – and “there are three ‘tomorrows’ in the title”.

This is characteristic of both Zevin and her soaring, wry, immersive and ambitious novel, the kind of book that will make you cry on public transport, think about it when you’re not reading it, recommend it to everyone who hasn’t, and then envy them for encountering it for the first time. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow plays on patterns and intricacies, winks from pop culture both ephemeral and established – Magic Eye images and Pac-Man machines side-by-side with Williams Morris and Shakespeare – while Zevin is an author who answers questions with well-considered theories, offered up like maths equations.

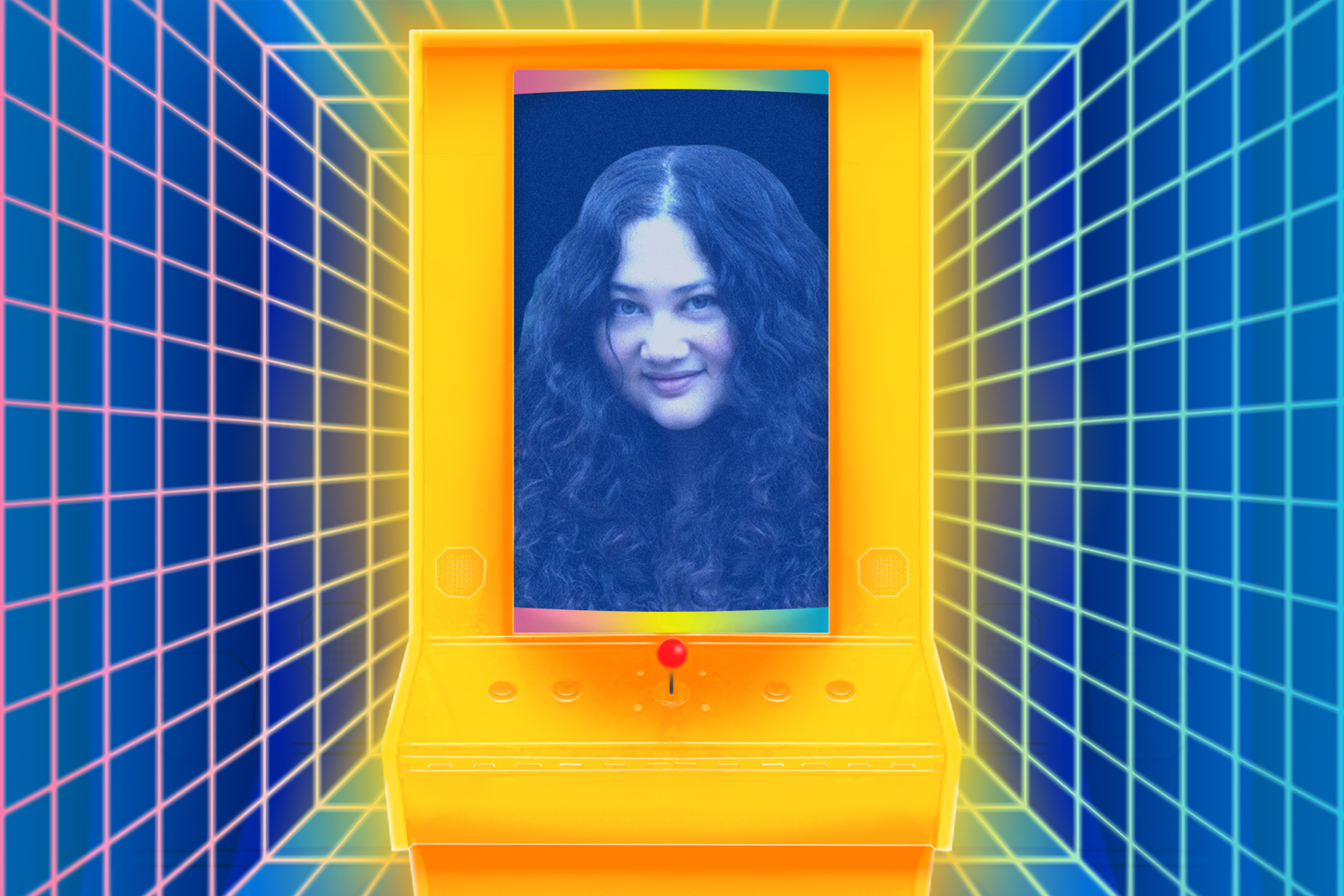

In Zevin's opinion “the book is largely about failure,” she explains from the accommodating cool of an air-conditioned meeting room. She lives in Los Angeles, but is visiting her British publisher while on tour in the UK, which is currently ailing beneath the sweaty palm of a heatwave. She wears a shiny green skirt and a white blazer, her face shrouded by a thick tumble of black curls.

Her agent, Zevin continues, suggested she steer clear of the 'failure' line – “He was like, ‘let’s not say that anymore,” she laughs – "but I feel it’s very much a book written by somebody who’s had some successes, had some failures, and had lots of things in-between as well.”

'I have written 10 books, which means I have done it all the ways, and I have no advice'

Gabrielle Zevin

At 44, Zevin has written 10 novels and three screenplays over the past 17 years. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is her second to debut on The New York Times bestseller list, after 2014’s The Storied Life of A. J. Fikry, (the film version of which, adapted by Zevin, will open next year). She speaks of her career with calm normalcy punctured with dry wit: “The people who have the best tips on how to write a novel have normally written one. I have written 10, which means I have done it all the ways, and I have no advice”.

And yet, the book is undoubtedly a success. Zevin’s been on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon show to talk about it, because the late-night host chose Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow as his inaugural book club pick. It’s been universally applauded by critics, some of whom have dubbed it worthy of the Great American Novel category.

The plot concept is simple: two outsider kids, Sam and Sadie, meet in a children’s hospital and bond over the computer games they play together there. We meet them as they are reunited on a subway platform near Harvard in the late Nineties when they are in their early twenties. Over the next 15 years they play and create games, alongside their producer and mutual friend Marx Watanabe. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is a story about friendship that will break your heart.

It's also about creativity and artistic ambition.

“There is a time for any fledgling artist where one’s taste exceeds one’s abilities,” the omniscient narrator of Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow tells us. “The only way to get through this period is to make things anyway”. Blink and you’ll miss it, but this is where video game designer Sadie Green pushes through, past her perfection and into brilliance. She does it because of Sam Masur, her co-creator, colleague and estranged friend. “It is possible that, without Sam (or someone like him) pushing her through his period”, the narrator continues, “Sadie might not have become the game designer she became. She might not have become a designer at all.”

In a novel of soaring success and gutting near-misses, the genesis of a main character is smuggled among other, arguably shinier things. The sumptuous depiction of the storm in the opening scene of Ichigo: A Child of the Sea, the game that catapults Sam and Sadie to stardom, for instance. Or the casual theft of a whiteboard from Harvard’s Science Centre. Fitting, really, for this elemental core of the novel to be hidden like an Easter Egg in a game.

The book sweeps across cities and decades, something Zevin attributes to the fact it was largely written in lockdown, although she started work on it in 2018. “I feel, in the description of places particularly, a palpable longing for places I could no longer go,” she explains. “They’re all cities I know, where I’ve lived or worked. I don’t think I’ve ever lavished that kind of detail on describing places before. Writing became a kind of travel.” She would visit these places multiple times: a key part of her practice is to read everything she has written of a book before sitting down to write more of it. Zevin estimates she has read the opening scenes “1,000 times, or something stupid”.

'Sadie's the character that is probably closest to me in most ways'

Gabrielle Zevin

Beyond physical places, though, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow takes the reader into created, gamified worlds: ones where you can die and start again, box-fresh. The title borrows from Macbeth’s soliloquy in the bleak fifth act of the Shakespearean play, and while grief does cast a heavy pall over the book, it encourages Zevin’s characters to make the games they design shine all the brighter.

It speaks to Zevin's deft touch that even readers who don’t identify as gamers will understand everything happening here, and even begin to see games, as Zevin does, as capable of powerful storytelling as any book or play. No wonder: the child of two IBM employees, she “just knew my way around computers in all the senses very, very early.”

“I remember feeling like the computer solved a really particular problem for me, which was the problem of solitude,” Zevin says. “I was an only child, and suddenly had someone to play with, which was a computer. Prior to having a computer, I if I played, I played alone, which is great practice for being a novelist, because if you're playing a game, you're imagining an imaginary opponent, which is not unlike creating a character.”

Zevin speaks quickly. She's unabashed about how much of herself is in Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. While touring the book she’s found that people – often men – have voiced their dislike of Sadie, who is fiercely determined, without realising that Zevin gave her a lot of her own personality: “She’s the character that is probably closest to me in most ways. And I think, 'Well, it's probably because you don't understand what it is to be a young woman with ambition, you know?' Otherwise, I think she's pretty understandable.”

As bi-racial characters, Sam and Marx also mirror Zevin, whose mother is Korean and father is Jewish. “I did want to write about the fact that there are multiple ways one can be bi-racial,” she says. “So much of Sam comes from my own experience. As a kid, everywhere I went, people were always sure that I was a foreigner. They were always sure that I was not from wherever I was at the time. That’s a strange way to go through life, I suppose."

“But also, I wanted to write about bi-racial identity in a more nuanced way than I had seen, because I often see a bi-racial character being used as a stand-in for not truly writing about race, so people don’t understand that experience is particular in a way.”

When she started writing, Zevin says, she thought of fiction as “a mask”: “I would consciously make the characters as little like me as possible, you know, because I didn't want anybody to possibly mistake me for people in this book. It gave me more freedom.” Over the years, she says the “mask slipped, and I started writing closer to myself.”

She attributes some of this to growing up with Korean heritage in a town that was two-thirds Jewish. “When I travelled to Asia as an adult, I became aware that I would have written entirely different books and been an entirely different person if I’d been raised in a place that was largely Korean or largely Asian. I might not have thought, ‘Hey, fiction is a great mask’”.

Zevin says that much of Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is enabling Sam to “see himself as more of a centre of the world, and not just some funny-looking kid sitting on the periphery of it.”

And maybe the book has done this for Zevin, too: taken her from the outskirts of the publishing world and catapulted her into its centre. Perhaps she doesn’t feel that way, in spite of the late-night shows and the headlines about the $2 million film deal that she will executive produce. Zevin has a rule: she only posts on social media for the three months after a book is released, and then she retreats into the quietude of her writing practice, what she describes as one of the unlikely upsides of enduring a failure – although things will be louder this time around.

As that nugget was hidden in the book’s first pages, so an admission of achievement is in our conversation. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is the book where ambition and reality have collided for her – that “long time where there’s a gap between your abilities and your taste” is over. “When I was writing, I said to my partner, ‘I don’t really care what happens with this book, because it’s exactly what I wanted to do,'” she says, looking at me. “And so that success was there.”

She stopped caring about external validation just as it arrived. Zevin wrote a book about failure, and in doing so, ended up winning.