How books shaped The Beatles

Beatlemania, the Fab Four, mop tops, Abbey Road. Peace and love, LSD, the Maharishi, Apple. Shea Stadium and Sergeant Pepper. Seventeen UK number one singles. The greatest band that ever lived.

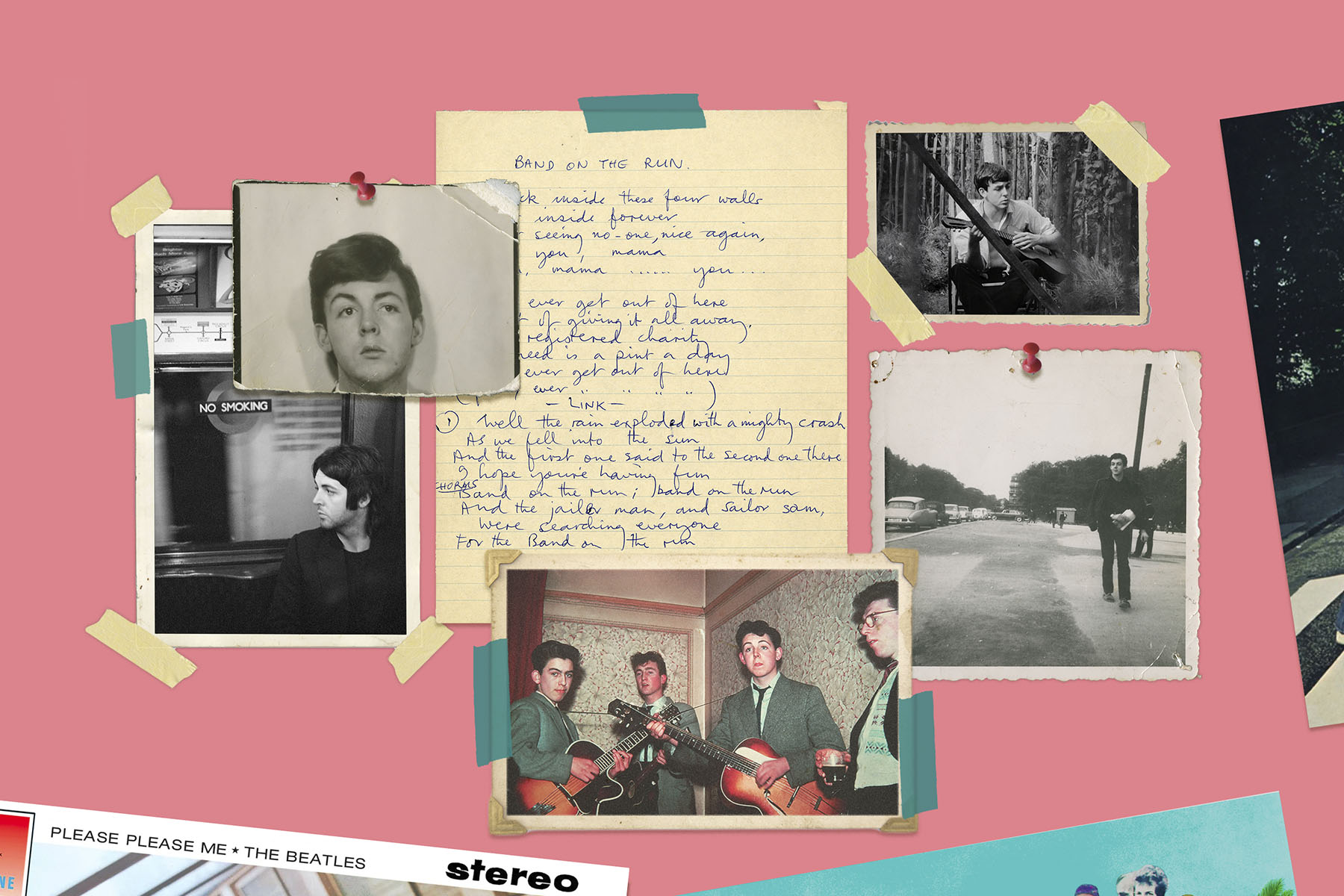

Many images and thoughts flash through the mind when The Beatles are mentioned. But the group is rarely associated with Chaucer, Shakespeare and Dickens. Yet Paul McCartney’s new book, The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, lays bare just how much he as a lyricist was inspired by these figures. Through analysis of 154 of his songs – from ‘All My Loving’ to ‘Yesterday’ – we see how McCartney’s work is not only influenced by the giants of literature but actually extends a tradition of poetry in English that stretches back centuries.

“There were always a couple of titles for this book. Words from a song, perhaps,” poet Paul Muldoon tells me. He edited the book having spoken to McCartney about his songs for around 50 hours over 24 sessions. “But I was very clear it should be called The Lyrics because that points to the lyric of the song but also to the tradition of the lyric poem. I was very keen that Paul be properly regarded as a literary figure.”

He took to Chaucer after Durband revealed just how clever and bawdy The Miller’s Tale was

Perhaps McCartney’s reputation as the affable Beatle, always first with a smile and a cheeky quip, detracted from his scholarly leanings. But his knowledge of literature, plays and poems leaps from The Lyrics’ pages. He talks of Dylan Thomas, Oscar Wilde and Allen Ginsberg, of French symbolist writer Alfred Jarry, Eugene O’Neill and Henrik Ibsen. His lyrics are peppered with links and allusions that revel in wordplay and homage.

The musician’s “capacity for textual analysis”, as Muldoon puts it in the book’s introduction, comes from a naturally inquisitive mind. A young McCartney would go to the Royal Court theatre in Liverpool and eavesdrop on other people’s conversations to pick up opinions, criticisms and turns of phrase. But his appreciation of literature was initially sparked by his English teacher at the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys, a man named Alan Durband.

Muldoon says that grammar school education in the Fifties was “really quite exceptional” in general. But he says Durband’s impact on the young McCartney cannot be overstated. “Alan Durband had a very good education himself. He was educated at Cambridge and that was extended to his own classroom. What Paul was exposed to there was really quite phenomenal.”

Durband had been taught by F.R. Leavis, the scholar and literary critic, whilst at Cambridge, and his passion for literature rubbed off on the teenage McCartney. “He inspired my love of reading and opened things up for me so much that I came to live for a while in a fantasy world drawn from books,” McCartney says in The Lyrics. He took to Chaucer after Durband revealed just how clever and bawdy The Miller’s Tale was. He even bought a copy of Thomas’s Under Milk Wood “just to see how Thomas dealt with words”. (So inspired was McCartney that he says he’d have become a teacher had the Beatles not worked out. Muldoon recently had him as a surprise guest teacher on his songwriting course at Princeton. He was “quite brilliant”.)

Muldoon recently had him as a surprise guest teacher on his songwriting course at Princeton. He was 'quite brilliant'

In terms of his teaching methods, Durband was “freshly minted” in a slightly new way of teaching literature, according to Muldoon. He was into ‘close reading’, which was a way of critically analysing a text that focused on individual phrases and wallowed in the resonance of detail.

McCartney’s expansive cultural education continued in London when he started dating actress Jane Asher. He moved into the Asher’s roomy townhouse at 57 Wimpole Street in 1963 and ended up staying for three years. The family – erudite and welcoming – took him under their wing. He started seeing Asher’s music teacher mother Margaret as a surrogate mother (McCartney’s own mother Mary died when he was 14). Together they’d visit plays and galleries. It was an “eye-opener”, says McCartney in the book. “The family knew all about art and culture and society.”

Muldoon says McCartney was “kind of adopted” by the Ashers. “They had quite a broad social base and it coincided with a time when London was a milieu in which the painters, the poets, the songwriters and the filmmakers interacted. I think the Ashers gave him stability. It was a stable base from which he could leap.”

And leap he did, taking everything he’d learnt with him. Durband’s love of detail can be detected in McCartney’s lyrics to Eleanor Rigby. It’s a song that revels in the minutiae, from the protagonist keeping her face “in a jar by the door” to Father McKenzie darning his socks alone at night. The musician is specific in his commentary in the book that Eleanor Rigby’s unnamed cold cream in the jar is Nivea. This specificity matters, says Muldoon, even though the brand isn’t named in the song. It puts the lyrics in context and roots them in reality. Such details are everywhere in McCartney’s work.

McCartney is also a fan of the nonsense writing of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Look no further than Yellow Submarine as an example

As is Shakespeare. “Lend me your ears” in ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’ came from Julius Caesar, while ‘The Fool on the Hill’ is a reference to King Lear (the truth-telling “fool” in the song represents Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, with whom the Beatles stayed in Rishikesh in 1968). The famous couplet that finishes ‘The End’ – “And in the end the love you take / Is equal to the love you make” – stemmed from McCartney’s fascination with how Shakespeare used couplets to close out scenes. Then there’s Dickens. ‘Jenny Wren’, a McCartney song from 2005, is a character in Our Mutual Friend.

But throughout his career McCartney has done far more than just borrow phrases, forms or constructions. He has, says Muldoon, brought “modern components to bear on the tradition”. His songs are almost mini-plays in which he paints scenes and conjures images. This links to McCartney’s other cultural influences: radio, TV plays, films and music hall songs. Their influence has been both general and specific. The gritty domestic realism of ‘She’s Leaving Home’ can be traced to the Wednesday Plays that he would watch on BBC1. The “pataphysics” that he writes about in ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ is a reference to a Radio 3 play of Jarry’s Ubu Cocu that transfixed him in the mid-Sixties. And the vaudeville soundbites and songs of the Sgt. Pepper album can be traced back to his musician father’s job as a spotlight operator at the Liverpool Hippodrome. He’d hear music hall tunes and replicate them on the piano at home.

McCartney is also a fan of the nonsense writing of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Look no further than Yellow Submarine as an example. “His interest in the nonsense tradition is quite profound, and the nonsense tradition is a huge tradition in the English literature,” says Muldoon.

The poet is aware that calling McCartney a major literary figure may sound a little overstated.

McCartney took all these influences and scrambled them together to make something unique and democratic. Notions of ‘high’ culture, ‘low’ culture or ‘pop’ culture didn’t exist: they’re just songs. There has never been any hierarchy of importance: Desmond Dekker, the reggae singer who McCartney admired, was as key an influence as Thomas Dekker, the Elizabethan dramatist who wrote the original Golden Slumbers. “All of that stuff is in the mix and you can’t say that Thomas Dekker is more or less important than Desmond Dekker,” says Muldoon.

The poet is aware that calling McCartney a major literary figure may sound a little overstated. “I’ve seen people say, ‘Paul Muldoon, why does he have to say Paul McCartney’s a literary figure? Does he really have to do that?’ I feel I do have to do that,” he says. Muldoon notes that musicians get a tough time when they are lauded as such. People lined up to “belittle and bemoan” Bob Dylan, for example, when he won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. Organisers of the prize said Dylan won for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”. Looking at McCartney’s body of work, only the grumpiest and most querulous of critics could argue that he hasn’t done similar in the British song tradition.

“Literature is a very very broad church,” says Muldoon. “And Father McKenzie is in the church as well as John Milton.”

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Ryan MacEachern/© MPL Communications Ltd/© Mike McCartney/© Paul McCartney / Photographer: Linda McCartney/