Floral fiction: a book-lover’s guide to the best flowers in literature

Spring has always been a time when we’re lured outside. The weather warms up, the days stretch out and the ground awakes. The air smells different, somehow, under trees laden with blossom. We find ourselves shedding our coats, turning our faces to the sky.

The extraordinary events of the past year have seen us depend on outdoor spaces more than ever. Parks and gardens have offered retreat, beauty and a space of escape when we’ve spent so much time indoors. During lockdown, those staying at home gardened more than they ever had before – and they read more, too.

Thousands of books have been written about gardening itself. Much of what can’t be gleaned from the soil must be determined from a book written by somebody who knows more about it, and the persistent surprise and ritual of the seasonal cycle has inspired many writers to put pen to paper.

But more interesting, perhaps, is how flowers and the gardens they grow in sneak into fiction. Authors have been relying upon the in-between constraints of a garden – those outdoor rooms, where cultivation and wilderness tussle with one another – to set the scene for centuries. Everything from seduction (Romeo & Juliet, Bridgerton) to deceit (Atonement, the Creation myth) has played out on the lawns we smell through the pages of a book.

Mrs Dalloway, of course, said she would buy the flowers herself.

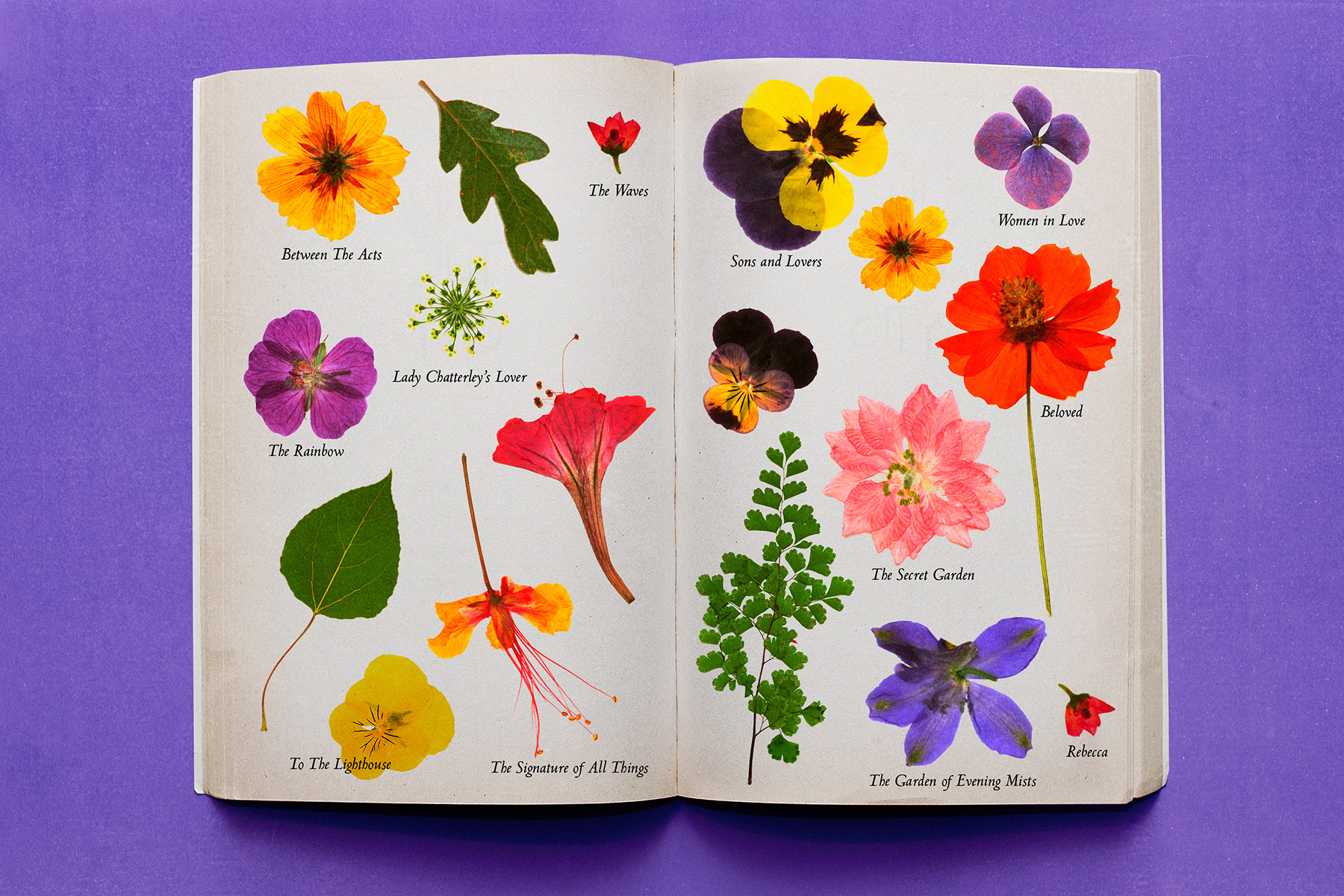

In some cases, flowers aren’t so much set-dressing as a sixth sense. Virginia Woolf wasn’t as much of a gardener as her husband, Leonard, nor her lover Vita Sackville-West, nor indeed her sister, artist Angelica Bell. Nevertheless, flora fills her writing. From Kew Gardens, Woolf’s 1919 short story, to Between The Acts (1941), her final novel, green spaces have held the delicate – and often devastating – interplay of the humans who tend to and enjoy them.

Mrs Dalloway, of course, said she would buy the flowers herself. In To The Lighthouse (1927), it is the garden of the Ramsay family’s holiday home on Skye where human life unfurls and, after Mrs Ramsay’s death, leaves the flowers to their own devices. During The Waves (1931), Woolf’s challenging stream-of-consciousness narratives swerve to the garden: “The flowers swim like fish made of light upon the dark, green waters. I hold a stalk in my hand. I am the stalk.”

Woolf’s contemporary DH Lawrence was a rare example of a writer who studied botany while at university. He dedicated poems to all sorts of flowers, among them geraniums (“As if the redness of a red geranium could be anything / but a sensual experience”), and wrote essays about flora around the world. While Woolf used flowers to demonstrate the passing of time, for Lawrence, plant life offered a means of engaging with our more primal selves. In Sons and Lovers (1913), The Rainbow (1915) and Women in Love (1920), the garden’s sensory powers are heightened during moonlight flits: flowers and their heady perfume offer a welcoming embrace the human world can’t provide.

Lawrence’s most infamous work, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (first published in1928, in Italy; in the UK in 1960), took this to history-making levels by positioning the garden – and the gardener – as vehicles of lust, passion and a state of truer being. Connie Chatterley and Mellors do all sorts, including cover one another in forget-me-nots in the middle of a wood (a fact that the botanically inclined enjoy for the sheer nerdiness of it: forget-me-nots are not a typically woodland flower, apart from in Derbyshire, where a particular woodland-friendly species exists quite happily). Mid-Century England may have harboured pride over their suburban plots, but found the notion of having sex in them unpalatable: Penguin was put on trial for indecency over Lady Chatterley’s Lover’s lover – and famously was acquitted. Literature – and gardening – was radically changed in the process.

If nature is unconstrained, then flowers have been used to demonstrate the luxury of freedom throughout literature. In Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), previously enslaved man Paul D maps his escape by following Cherokee advice to “follow the tree flowers. As they go, you go. You will be where you want to be when they are gone.” The garden of 124 Bluestone Road, the sad and haunted home where much of the Morrison’s story is set, transforms from one of abundance and jubilation under Baby Suggs’ care, to a site of horrific trauma after her death. In Beloved, what the ground holds – from brambles and berries to the bodies of children – helps to tell the story of slavery’s long and traumatic legacy. The extent to which the land is a safe space, it is suggested, is dependent on the actions of those who claim ownership over it.

Setting her book over three decades, Tan tells us something else in the process: that gardens, like grief, take time

But gardens can heal, too. It’s a concept we’re introduced to early: 1911 children’s book The Secret Garden, by Frances Hodgson Burnett, remains a much-loved story about the benefits of play and outdoor pursuits more than a century after it was published. The calm and reflection offered by tending to a garden is beautifully expressed in Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists (2012). Prisoner of war Teoh Yun Ling wants to make a garden to help her grieve for her sister – also a prisoner – and gives up a job as a war crimes judge to serve an apprenticeship to a Japanese gardener. Setting her book over three decades, Tan tells us something else in the process: that gardens, like grief, take time.

While many authors call upon familiar flowers – the smell of phlox at night, the generosity of roses - not all of the plants we encounter in books are real. Some merely play with reality to set the scene. Take the 50-foot high, deeply ominous rhododendrons of Daphne De Maurier’s Rebecca (1938): “crimson faces, massed one upon another in incredible profusion, showing no leaf, no twig, nothing but the slaughterous red." JRR Tolkein, meanwhile, housed Elves in Mallorns, encouraged hobbits to smoke Pipe-weed and filled Gondolin with Simbelmyne in his Lord of the Rings (1955) series. Hogwarts herbology students tended to Mandrakes, dodged the whomping willow and turned to Gillyweed to breathe underwater.

'Climate crisis and social justice are changing how we garden and how we understand our gardens'

Others delve into the rich and often murky world of botanical history to set their scene. Gardening, plant heritage and botany are intrinsically entwined with the less beautiful story of colonialism and empire. Elizabeth Gilbert encompasses both in her enthralling The Signature of All Things (2013), about Alma Whittaker, a singular botanist in a man’s world, who travels to Botany Bay for unrequited love of both a man and plant. Read it, and you’ll never look at mosses in the same way again.

Gardening may seem like a timeless endeavour; we reap and sow, just as generations have before us. But climate crisis and social justice are changing how we garden and how we understand our gardens. As we allow the storytelling of our gardens (and the flowers in them) to become more inclusive, we broaden the horizons of what these spaces can hold. With them, more beautiful, provocative and insightful books on flowers lie ahead.