Virginia Woolf’s (not so) secret lesbian relationship – in her own words

Virginia Woolf’s work is much loved and studied, but her intimate relationship with fellow author Vita Sackville-West is rarely more than an overlooked footnote. Yet this relationship was absolutely formative for both women. After their first meeting at a rather disastrous dinner party in 1922, Virginia and Vita exchanged fascinating, flirty, lyrical letters all the way through to the Second World War, and Virginia’s suicide, nearly 20 years later. And what could be more revealing than a letter?

Perhaps only a diary? This edition of the Love Letters includes extracts from the women’s diaries alongside their letters, which brilliantly highlight their contradiction, hypocrisy and yearning. Along with a fresh introduction from creator of Fun Home and the ‘Bechdel Test’ Alison Bechdel, the Love Letters uncover new perspectives on the lives and work of this extraordinary couple.

We might now be tempted to think of these women of bisexual, but we must be wary of retrospectively applying anachronistic labels. Certainly both women were happily married: Virginia to Leonard Woolf, a writer and social reformer with whom she ran their Hogarth Printing Press (he also often acted as chauffeur to drive Virginia to Vita’s home…). Virginia and Leonard’s relationship was one of much mutual devotion though not, it would seem, much marital consummation. Vita was likely Virginia’s first extra-marital relationship; Vita, on the other hand, had many affairs with men and women, before, after, and during her time with Virginia. Vita’s open relationship with her husband Harold Nicolson is described by their son Nigel in Portrait of a Marriage, but can also be glimpsed in the evocative extracts of their letters included in this collection: "Darling, there is no muddle anywhere!" Vita writes to Harold, a week after telling Virginia that she loves her, "I have gone to bed with her (twice), but that’s all." (That’s all!)

'If Virginia and Vita had had smartphones, what a stream of sexting acronyms would sift through our fingers'

Instead of lesbian, gay or bisexual, the term most commonly used by Vita and Virginia to describe their "proclivities" is "Sapphist": a euphemism after Sappho, an ancient poet of sensual verse about women, who lived on the Greek island of Lesbos (inspiring, too, the word ‘lesbian’). In one of her earliest diary entries about her, Virginia writes that Vita is "a pronounced Sapphist, and may […] have an eye on me, old though I am."

When trying to work out her own feelings for Vita, a couple of Christmasses later, Virginia writes again, "These Sapphists love women; friendship is never untinged with amorosity […] What is the effect of all this on me? Very mixed." When it comes to their letters to each other, though, they don’t shy away from talking about the physical side of sapphism. "Dear Mrs Woolf," writes Vita, "(That appears to be the suitable formula.) I regret that you have been in bed, though not with me – (a less suitable formula.)"

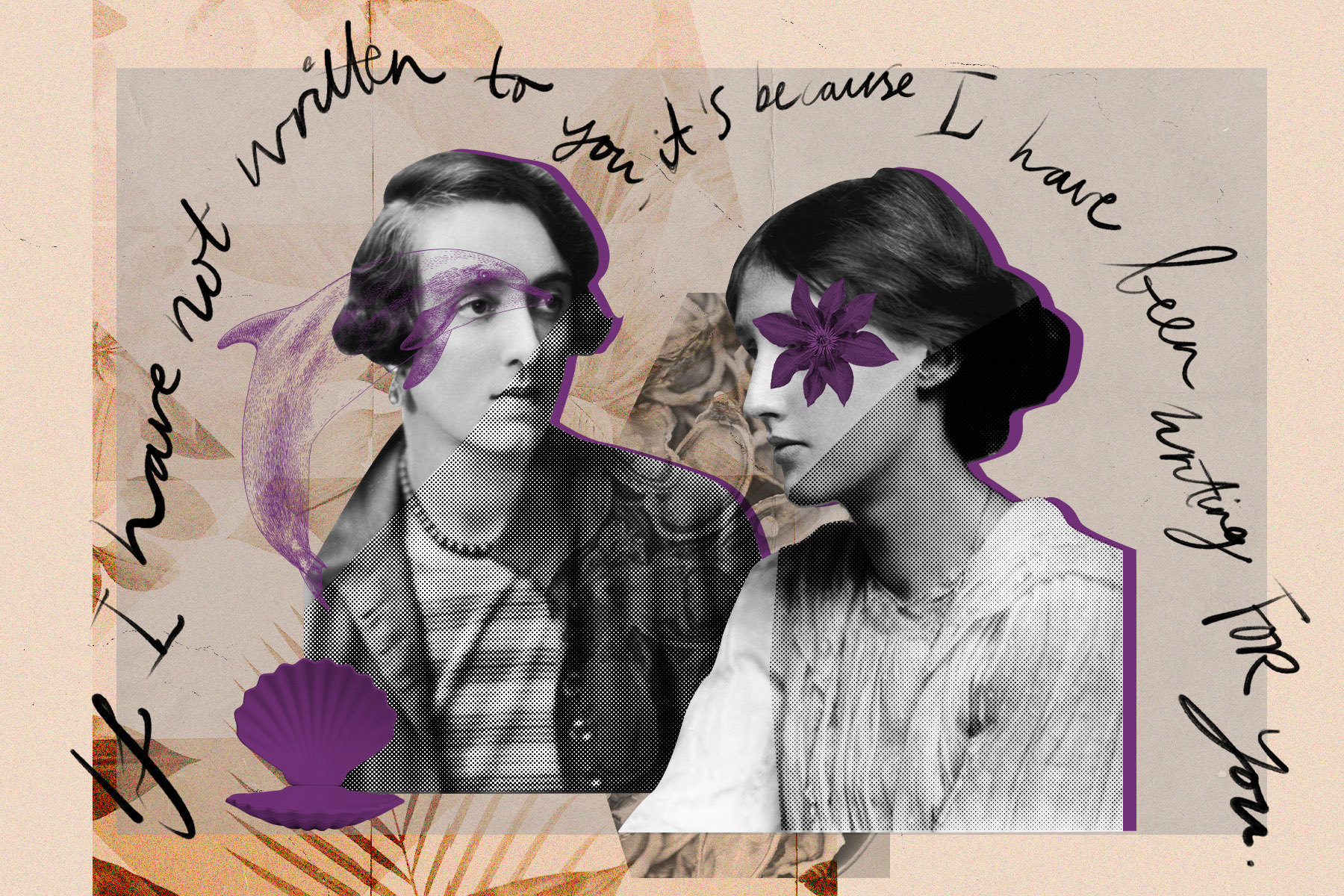

They developed intricate codes and in-jokes, too. When jealous at Vita seducing other women, Virginia imagines her as a "dolphin", eating "a whole bedfull of oysters" – and can’t resist cutting and pasting an illustration of a dolphin, "executing amusing gambols". Writing how much she misses her, Vita later replies with an oyster doodle.

Alison Bechdel writes in her introduction, "If Virginia and Vita had had smartphones, what a stream of sexting acronyms, obscure emoji (Scissors? A Bosman’s potto [a small primate]?), Twitter links to TLS reviews, and endless snapshots of Alsatians and spaniels would sift through our fingers in lieu of this magnificent paper trail."

These letters are so relatable that you often forget they were written almost 100 years ago. Yet much of their fascination and fun for the modern reader comes from the moments we remember that these are physical letters, being written and sent to each other. Letters get lost. They take a long time to arrive. Sometimes, worried they’ve been misunderstood, they are followed-up with an urgent telegram.

'Your letters are always a shock to me, for you typewrite the envelope, and they look like a bill, and then I see your writing'

Early in their relationship, Vita travels round Teheran with her husband, writing beautiful descriptions to Virginia every step of the way – she writes yearning replies from Bloomsbury, not knowing how long it will take to reach back across the sea.

Vita and Virginia played with all sorts of games with the medium. They sometimes handwrote (Virginia using her distinctive purple ink), sometimes used a typewriter, and sometimes both: "Your letters are always a shock to me," writes Vita, "for you typewrite the envelope, and they look like a bill, and then I see your writing. A system I rather like, for the various stabs it affords me."

They wrote on different kinds of paper – "This writing paper appeals to me so much that I must write you a letter on it," writes Vita, on some particularly quirky hotel-headed paper. When Vita is published by Virginia and Leonard’s Hogarth Press, she sends multiple letters within the same parcel, one for her editor, one for her lover. When Virginia has her portrait taken, she sent copies to Vita. In fact, one of these photos would remain on Vita’s writing desk from that point onwards. Her Sissinghurst home remains as Vita left it when she died, decorated with two photos: one of her husband, and one of Virginia.

They are both wonderful wordsmiths, of course, and take great pleasure in the art of letter-writing – they are trying to impress each other, both in flirtation and as competitive poets.