‘This novel had everything’: an oral history of Ian McEwan’s Atonement

Ian McEwan was 50 when he embarked upon the notebook “doodles” that would become Atonement, an age that he reckons “is around about the peak, for a novelist”. While he was hardly an unknown – his previous novel, Amsterdam, won the Booker Prize – McEwan’s eighth novel is arguably his most famous (and, he’s admitted at times, his favourite). It has sold 1.5 million copies in the UK alone and been published in 42 languages. It carries quite a mantelpiece of gongs – The Whitbread, the Critics Circle and the Boeke Prize among them. When adapted to film in 2007, it earned six Oscar nominations and galvanised the careers of Keira Knightley and James McAvoy. Playing McEwan’s unforgettable protagonist Bryony Tallis confirmed 12-year-old Saoirse Ronan’s talent as prodigious.

And yet, for all those glittering accolades, Atonement’s legacy runs deeper than just turning its author into a household name. When McEwan started publishing fiction in the Seventies, he’d earned a Private Eye nickname of Ian Macabre: his novels were littered with unflinching and detailed accounts of grisly dismemberments, kidnappings and euthanasia pacts. But Atonement opened on a sweltering midsummer’s afternoon in an English country house as a girl on the cusp of adolescence tried, in vain, to stage a play for her brother’s long-awaited return. As The New York Times wrote at the time: “here is McEwan, at the helm of what looks suspiciously like the sort of English novel that English novelists stopped writing more than 30 years ago.”

As readers would discover, Atonement – fundamentally a love story with a devastating deceit at its heart – was also a feat of literary engineering. It unleashes its despair and unease like a dripping tap: gradually and unstoppable, until only deluge remains. A novel made of three separate stories, with a remarkable twist at the end, Atonement was that rare thing: a book devoured in literary circles that also sold by the thousand in supermarkets. Within four years of release, it was included on the OCR A Level exam syllabus for English Literature.

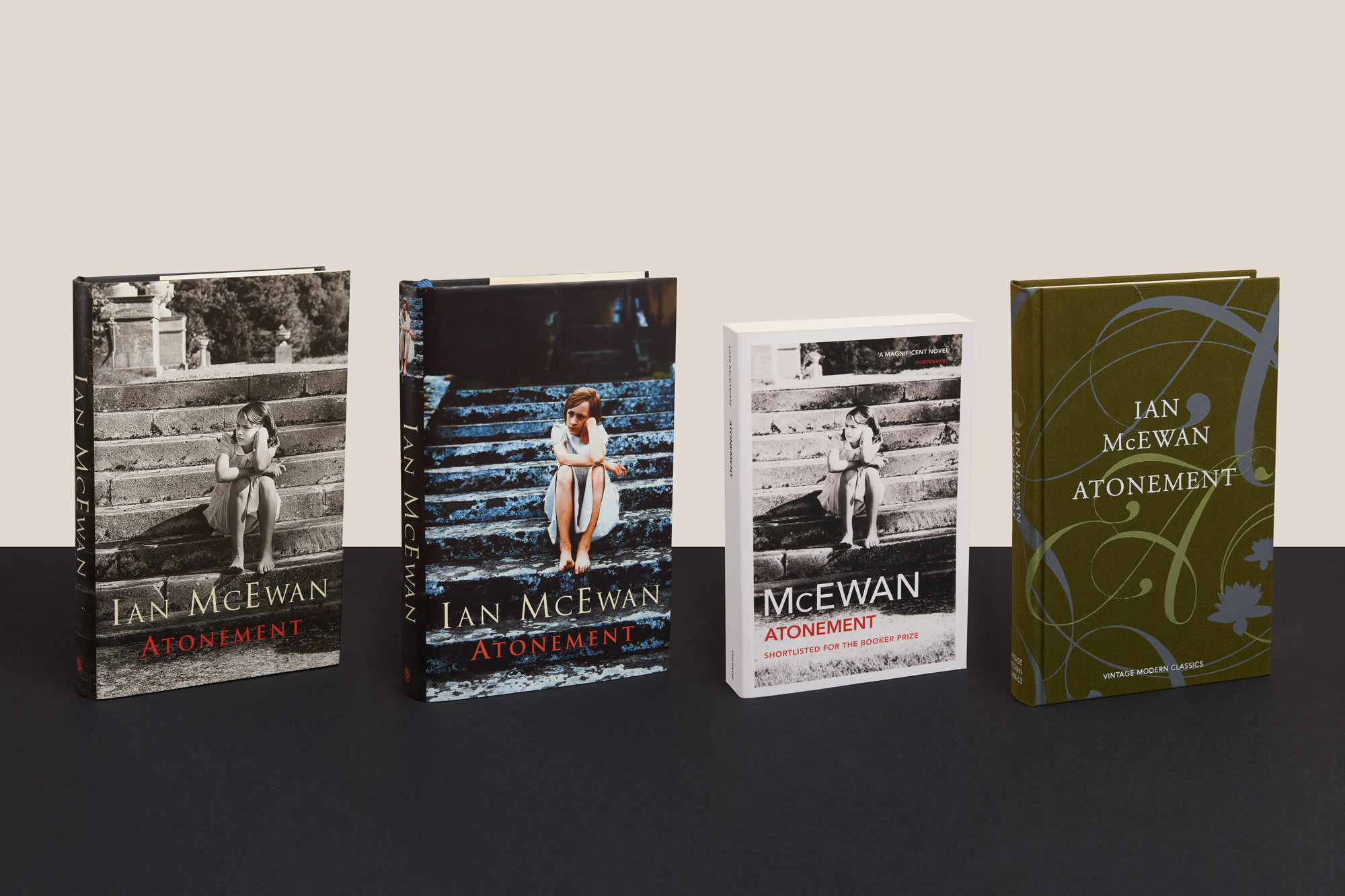

It also had its own remarkable story. Emerging from the ruins of a disregarded sci-fi short story, Atonement was filed rapidly and in parts, the novel’s crucial final section arriving only after production had already begun. Along the way, McEwan changed the title at the last minute, and the publishing house embarked on one of the largest photoshoots it had undertaken to take a risk on what became its most enduring cover. What resulted was a collision of publishing good fortune – and one of the greatest books of the 21st century. In the centenary year of publisher Jonathan Cape, and 20 years since it appeared in bookshelves, here’s how Atonement happened, according to the people who were there.

In the late Nineties, Ian McEwan’s stock as a novelist was rising – and fast. Enduring Love, his 1997 novel, topped the bestseller charts. A year later, Amsterdam was released and won The Booker Prize.

Ian McEwan, author: Sometime round about 1997, I made some notes that were about the end of the century, and looking back and realising that there were errors we made – the two World Wars in particular, the Holocaust – that we could never correct; that we could try to correct but the effort would be protracted.

Dan Franklin, former Publishing Director, Jonathan Cape: He says he wrote the beginning of Chapter Two, and that was the beginning of the whole thing, and he wrote it somewhere weird, like Costa Rica or something, while he was on holiday two years before.

Ian: That didn’t lead to any actual fiction, but while away on holiday with my sons I had a couple of hours and found myself writing maybe a paragraph, maybe two paragraphs, about a young woman coming into a rather ornate, classical drawing room of a country house with some wild flowers that she had just picked, looking for a vase, and she was aware of a young man outside who was a gardener. She wants to see him and she doesn’t want to see him all at once.

Dan: And you have the sense that he had something.

Ian: When I got to the end of that, I didn’t do anything about it but I knew that I probably started something.

Dan: There’s a thing with Ian’s books; I published many, many books with him. At a certain point they just got faster and faster.

Ian: So the Booker was 98. Was that Enduring Love? No, it was Amsterdam. I was already writing this when the Booker happened.

Peter Straus, Ian McEwan’s current literary agent: At that point there was a momentum, and quite rightly, for Ian who was writing these extraordinary, brilliantly crafted books. There was this excitement and expectation of what would come next.

What would become the second chapter of Atonement was, briefly, a science fiction short story, which McEwan abandoned.

Ian: I came back about 18 months later, rejected everything about it, realised I was now back with my earlier note of coming to the end of a century, and that the actual moment I described – with wildflowers in the vase – was pre-War. And at that point I was liberated. I suddenly rewrote that chapter in a completely different way, it then became the second chapter of the book as published. I wrote another chapter that I knew would proceed it, which was about that young woman’s younger sister, Briony.

Peter: I think he was concerned that this was a mad idea: the narration, the way it was constructed, that the critics would not like it.

Ian: Pretty early on I had the structure, which was three novellas and a coda, that’s what I thought of it. One portion, about 65,000 words, was set in 1935. Then it was 1940, and then it brings us to the very end of the century, 1999, at which point the reader becomes aware that they’ve been reading a novel by its principal character. And it ends with Briony’s initials. And then we go into the coda which is related by the first person, in the present.

Peter: He said, "Oh god, I thought, a Second World War Book, they’re never going to buy that".

Ian: I remember, when I was still writing it but coming towards the end, I said to Dan: "I know you want a new book from me, but just warning you, this book is very much a book for writers. It’s a book about the imagination and what it means, what the power of the imagination is and what the power of writers is. And if you can sell 15,000 copies in hardback I’d be delighted." And Dan said, "Oh, ok, fine." And when he read it he said, "You’re completely nuts. It’s got all the ingredients, not only of a literary book, but it presses three buttons for a popular book". I said, "Well, what buttons?"

Dan: I don’t know how you put it into words but it was just that instinctive thing. It had so many elements. Even looking at it completely cynically: it had The Go-Between in the first part, it had fantastic war material, and then it had this amazing meta-physical trickery at the end. So you were kind of getting everything. And so lucidly and so brilliantly that we were simply purring.

Ian: I said, “oh, well, that’s why I’m not a publisher”. I had no idea.

Roger Bratchell, Marketing Director: This novel had everything: the sultry pre-war setting, the war, the twist. It was Ian in excelsis.

Atonement was produced very quickly – McEwan filed at the start of the year, just months before its September publication.

Suzanne Dean, Creative Director, Vintage: Dan gave me a manuscript, one of those ones that were printed out on the black-and-white printer. Dan had said, “We’re going to be publishing this, you better start reading it now”. I think it wasn’t a whole manuscript at that point, Ian was still writing it.

Roger: Dan would announce at some stage "there's a new Ian due. He's sending it to me some time soon." About a week later it would arrive, fully formed, perfect in every way. It would be your 'job' to read it over the weekend. The excitement with this book was palpable.

Ian: I gave Dan the first three chapters, but I was still writing the coda. And I hadn’t told him, or if I had told him he’d forgotten, but I had to go and give a talk on the other side of the world, on Vancouver Island. I was racing to finish this last 8,000 words, and I had just got it, late at night, before catching my plane the next morning. I couriered it round to Dan from Oxford.

Pascal Cariss, copy editor: I remember that publisher’s cliché about there being a real buzz in-house about a manuscript was, in this case, absolutely true. Everybody picked up on the whisper that this was a very powerful and dramatic story. Everybody wanted to get their hands on a copy and read it as soon as possible.

Ian: The book had already circulated among Cape people. And they’d all read it, thinking they had the whole thing, and were happy with it. They had no idea there was more! They’d already said, “We love it, it’s marvellous, the way it finishes." And I said, no, no, there’s more, it’s on its way to you. I began to think, when I was on the plane, well, they might not like this development, where everything that’s happened turns out not to have happened.

Roger: There was always a signature twist. So you read it looking out for "the moment".

Ian: Fortunately, they liked it even more.

Roger: There was a kind of hushed awe when people had read the typescript – we just knew this was going to be huge.

The team worked quickly on the novel’s production, putting it through edits and copyedits. Meanwhile, Suzanne, Dan and Ian set to work on Atonement’s cover.

Suzanne: It was my second year in the job. I hadn’t worked on a hardback with Ian, and this was obviously a big title. I remember that excitement in-house, the absolute, “oh-my-god this is just amazing”. And the speed of working like that with such a huge project.

Ian: My first thought was, “We’d quite like a picture of this girl, lying on her stomach on the library.”

Suzanne: Dan had told me after I’d started reading it that Ian wanted a photograph of a girl reading in the library. That was my brief. It’s a period piece, and so we started off by trying to find original photographs from the right time, with the right kind of look. There was absolutely nothing out there. I searched all the libraries. Which then made us think, “Ok, this means a photoshoot.”

Dan: I was very heavily involved in the cover in a way that I’m usually not.

Suzanne: Dan came along because it was such a big shoot, he wouldn’t normally.

Dan: We had this vision of what the cover art should be, which was of Briony lying on the floor in a old-fashioned library with wood panelling walls, reading a book. We then did a lot of searching for a country house, with a library, with wood-panelled walls, that we could use for a photoshoot. We found this house, I think it was near St Albans.

Suzanne: I remember we all got into this huge minibus, went off to the other side of the M25, somewhere like Milton Keynes. To this incredible country house.

Chris Frazer-Smith, photographer: It’s near Hemel Hempstead, it’s called Gaddesden Place.

Suzanne: I think this photoshoot was the equivalent to almost like a small movie. That’s what it felt like. I had never helped to organise a shoot as big as this – ever.

Chris: We had hair and makeup, we had two assistants, we had a guy running the lighting at my direction because we needed to light certain things… it wasn’t a very big crew.

Suzanne: We had to find the girl first and the girl had to have the right look. We had a shortlist, and once we had the girl approved, she was sized up for the clothes. We got the dress made because she had to have the right kind of dress, and it was quicker. It was expensive to do this but it proved worthwhile in the long run.

Chris: The model posing as Briony was very confident without being rude, and she took direction really well. And I think she found the whole notion of dressing up in a summer dress, having her hair done, all slightly amusing.

Suzanne: She came out wearing her white dress, she looked so the part, so immaculate, the period was right, everything was right.

Chris: It was 20 years ago so I was shooting film, and I was shooting slide film. We shot black and white each time, on medium format cameras. We shot at the garden at the back of the house; we shot shots of her standing, with her arms folded, looking really grumpy.

Suzanne: We spent the whole morning photographing loads of poses in the library, and then we went outside after lunch and she stood in the field and there’s some shots of her standing in long grass, which were ok. There wasn’t one that stood out among that. By that point, it was going to be the library that’s the best shot.

Suzanne: Then I saw the steps, and I thought, “I want the steps as well”. In the book, everything pivots on the moment in the steps by this bridge.

Chris: I said, "Let’s sit on the steps". Like all kids at that age, after a while she got bored and fidgety and that played into our hands really quite well. I would normally have waited for the cloud to cover the sun, but I thought, sod it, I’m just going to shoot – we’d probably been there a good seven hours by now, so we were wary that she wasn’t going to give us much more. She was literally saying to me, “Mister, have you taken the picture?”

Dan: The day was going on, and on, and on, and on. And the girl was getting crosser and crosser.

Suzanne: The sun was starting to set behind some trees, and she was starting to scribble with a stone on the floor.

Chris: The way she was sat on the steps, I could see it. I think I shot two rolls of black and white film on those steps, and I thought, “that’s great, there’s something really nice about that sequence of frames.

Dan: There she was, sitting on the steps, and she is stamping one of her legs in fury, she just wanted to be out of there, and Suzanne and I were standing, watching this from behind his shoulder, looking at the scene.

Suzanne: I turned to look at Chris, and Dan was standing behind Chris and I was nodding, and he was going, “yeah”, and we had all had the same idea at the same time, because she was so natural. She wasn’t thinking about us, she was just thinking “I’m bored”. And you can see the way her head is on her hand, she’s leaning forward and her foot’s up, she’s just in a world of her own. And that’s the difference, that shot. It’s so perfect. And we knew, and everyone turned and looked at each other, and it was like a shiver, we just knew it was the shot. It was amazing.

Dan: I think it’s the only time it’s happened to me: literally, our hair stood on end for that one shot. One knew instantly that this was it. And that it was, it was gonna be one of the great covers.

Chris: And I said, "I think we’ve got it".

After the shoot, the photographs were whittled down to a select few. Their first showing was unlikely: at a publishing dinner for another Cape author.

Ian: My memory was of being at some dinner. Might have been Julian Barnes, might have been Martin Amis, I can’t remember.

Dan: If there was a dinner it would probably have been for Julian. I don’t think we gave a dinner for Martin in all my time at Cape. Parties, yes, but not dinners.

Ian: Dan and Suzanne produced an envelope containing four pictures.

Suzanne: I wasn’t there! Dan was and he presented it and the next day he came into my office and said, “You got four gold stars from everyone yesterday evening”. I was like, oh my god. Can you imagine? Showing all that work. But I was new, you know.

Dan: The way Suzanne works is extraordinary. With the big authors she will prepare different jackets, and she’ll print them all out and spread them out on the table and have the author come in and go through them.

Suzanne: I had the big yellow photography boxes under my arm, I remember putting it down and giving Ian the actual prints, those big wonderful prints.

Dan: She and I will be there, and we’ll know which one we want them to choose.

Suzanne: I think at that point we all really, really wanted the picture on the steps, but we were still trying to persuade him. We were showing him, like, “Look how wonderful the steps look! We could have that on the back of her slightly curled round, and on the front this one.”

Dan: He’ll almost certainly deny this, but we had quite a hard time selling it to Ian, who wasn’t sure. But we knew at once, and that’s quite rare that that happens.

Ian: I must have gone in. We all agreed that the one on the steps was the one.

Roger: Suzanne Dean's magnificent jacket – just a brilliant image to work with. Intriguing, redolent of a time and age that conveyed glamour and mystery, that stopped you in your tracks.

Peter: The fact the jacket is still being used – what does that tell you? Twenty years on it’s still the jacket. It’s still good.

Work was nearing completion on the book’s publication when McEwan realised something needed to change - the title.

Dan: The major thing was that, when it came in, the novel was still called An Atonement.

Ian: I nearly always show my finished drafts to the historian Tim Garton-Ash. He phoned me about it, and he said, "I’ve got one thing I absolutely have to ask you to change, and I don’t want to ask you over the phone, I’m coming round to your house. Now."

Peter: I think Timothy Garton-Ash suggested he drop the “An”.

Ian: He lived just around the corner so he came round, and I don’t know if he went down on bended knee but he said, “Please change the title”. He said, “It’s clumsy on the tongue”. And I said, “Well, I just wanted to be a little modest about it.” And he said, “Don’t be. Please call it Atonement”.

Dan: Ian rang up and said, “Change it”. Which is minor but incredibly significant.

Ian: I phoned Dan and said, has it gone to the printers yet? I must have already corrected the proof. And he said, “yes...” very warily. “What do you need to change?” I said, “The title is now Atonement, not An Atonement”. And Dan said, “oh phew, thank God”.

Dan: You saw it at once, it was the right thing to do.

Ian: Dan hadn’t told me that he hadn’t liked it.

Roger: To add to the mystique of the book came the author's request to change the title from "An Atonement" to Atonement. What could it mean? We were sent scurrying back to the book to look for meaning. Some of the printed typescripts might have had the original title – I can't remember, but they would have been collectable. Mine, unfortunately, went to a deserving bookseller.

Atonement was published on 20 September 2001 and was nominated for the Booker Prize shortly afterwards.

Peter: I think it was delivered in the summer. They didn’t do proofs, because there wasn’t time. That led to the excitement and buzz about the book.

Roger: We decided to produce bound typescripts as the book was perfect. This was before the days of social media, so it was a question of just getting people to read it.

Ian: There certainly was a launch party. You’ll have to ask Dan.

Dan: I can’t even remember where the launch party was.

Ian: Cape gave so many good parties. The nature of launch parties is that they breed a kind of amnesia – if you can remember it, it was no good.

Peter: There was excitement. There was excitement that Ian had written another book, the minute he had written it people wanted to share their excitement and their joy.

Dan: I remember the reviews were amazing and everything was wonderful.

Ian: There were some lovely reviews. Most of us, novelists, are used to publishing a book and you get a good kicking somewhere and you get praise somewhere else and you just have to take it all in the run of things and the mix of things. This, for once, had a kind of unanimity.

Peter: It came out in the autumn and dominated the lists, dominated the Booker and while it didn’t win, it was certainly the book.

Roger: I can't actually remember publication day, but I remember the reviews and the sales. I remember the gnashing of teeth when it didn't win the Booker.

Before long, conversations were underway about an adaptation. Atonement the film starred Keira Knightley and James McAvoy, and forged Saoirse Ronan’s career. It went on to be nominated for six Oscars, win one, and take more than £84 million at the box office.

Tim Bevan, film producer, Working Title: I encountered Atonement around 2002; quite early on because it was successful and there was already a race for the film rights to it. The two director / scriptwriter combinaitons being discussed were Richard Eyre and Christopher Hampton, and Tom Stoppard and John Madden. And Richard and his team came to us, basically, to back it. I think [producer] Robert Fox was also part of that group.

Ian: I made a decision in around 1996 to stay away from screenplays, and that’s why, when Christopher Hampton was mentioned, I was delighted.

Stephen Durbridge, Ian’s film agent: It’s very easy to ring a film producer up and go, “I’ve got this wonderful McEwan novel, would you like to read it?” They tend to jump at it, really. But here, Robert Fox was one of the very early people to read it and he then went and talked to Working Title.

Tim: So we commissioned a script. We knew it was going to be a tricky one, because it has literary conceit at its heart. How are you going to make it interesting as a film?

Stephen: It was a difficult film to make because it was a pretty serious subject and it didn’t have obvious commercial appeal – it wasn’t a thriller or a comedy. I think there was a lot of tussles over the budget level and so on and so forth.

Ian: All these initial conversations were about the difficulty of translating this idea of whether things happened or didn’t happen, onto film.

Tim: We really scrutinised how to make this literary trick work cinematically. Into the mix came Anthony Minghella. He sat with Joe [Wright, director] and he said, “I’m not going to write anything here but I’m going to intellectually make you answer every question that I’m going to put to you about the story and script”. Anthony had done The English Patient, so in terms of literary adaptation he was one of the best in the world. It was absolutely Christopher’s script, but it absolutely needed that input from Anthony for the idea to emerge.

Stephen: I went to a screening of it very early on and there were a number of industry people there and the distributors. And I asked, "What are all those cards on the table?” And there was the release date of the movie in about 15, 16 territories. And I thought to myself, "Yes, we’ve got this right".

Tim: The thing is, great novels, it’s pretty nerve-wracking turning them into films because the literary audience have a great vision of what that might be. I remember showing Eric [Fellner, producer] the movie and he came out and said, “Don’t change a frame.” That never happens.

Ian: When you’ve got a film that had quite a strong commercial budget, you can be pretty sure that the novel is going to be wrecked. And in this case I think it was very, very sensitively handled. I think Joe did an amazing job. He’s a very gifted director.

Tim: I never knew whether Ian liked the movie or not to be honest with you. He sort of went with it. And he sold a lot of books off the back of it.

Ian: It delivered an enormous number of readers off the back of the film. So that was a whole new experience for me, to be in dump bins in supermarkets.

Dan: I loved it. I re-watched it at some point during lockdown and still loved it.

Roger: The film was the icing on the cake.

Stephen: Did one go into it thinking, oh god, if we sell the rights here is someone going to win an Oscar? No. But when your breath is taken away by something as it was when one first saw that film, then you start thinking about that.

Twenty years on, and Atonement has sold more than 1.5 million copies in the UK alone. It’s true legacy, however, is difficult to measure in sales figures.

Dan: Atonement was absolutely the turning point. Until then, Ian had this reputation for being dark, because of his early books and short stories. But this wasn’t like that. Atonement was like, somehow, the sun had come out. And it did. It certainly changed his critical reputation and it changed him as a prospect for the book trade.

Peter: There are very few books that enter the public cultural consciousness and become totemic. Atonement is one of them.

Suzanne: It’s what you call an iconic cover. There are some that are so entwined with the book and that really is the definition of iconic. What a lucky person I am to have been there, to work on that. That’s one of the most incredible experiences since I’ve been there, all those years.

Ian: I don’t know what it would be like to have an Atonement every time you publish but it’s not a given to literary writers. Most of us have a book. There’s always a degree of serendipity about starting a novel and I seem to have had buckets of it with Atonement.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Stuart Simpson / Penguin