- Home |

- Search Results |

- My mother, the pioneer: how Buchi Emecheta captured immigrant life in 1970s London

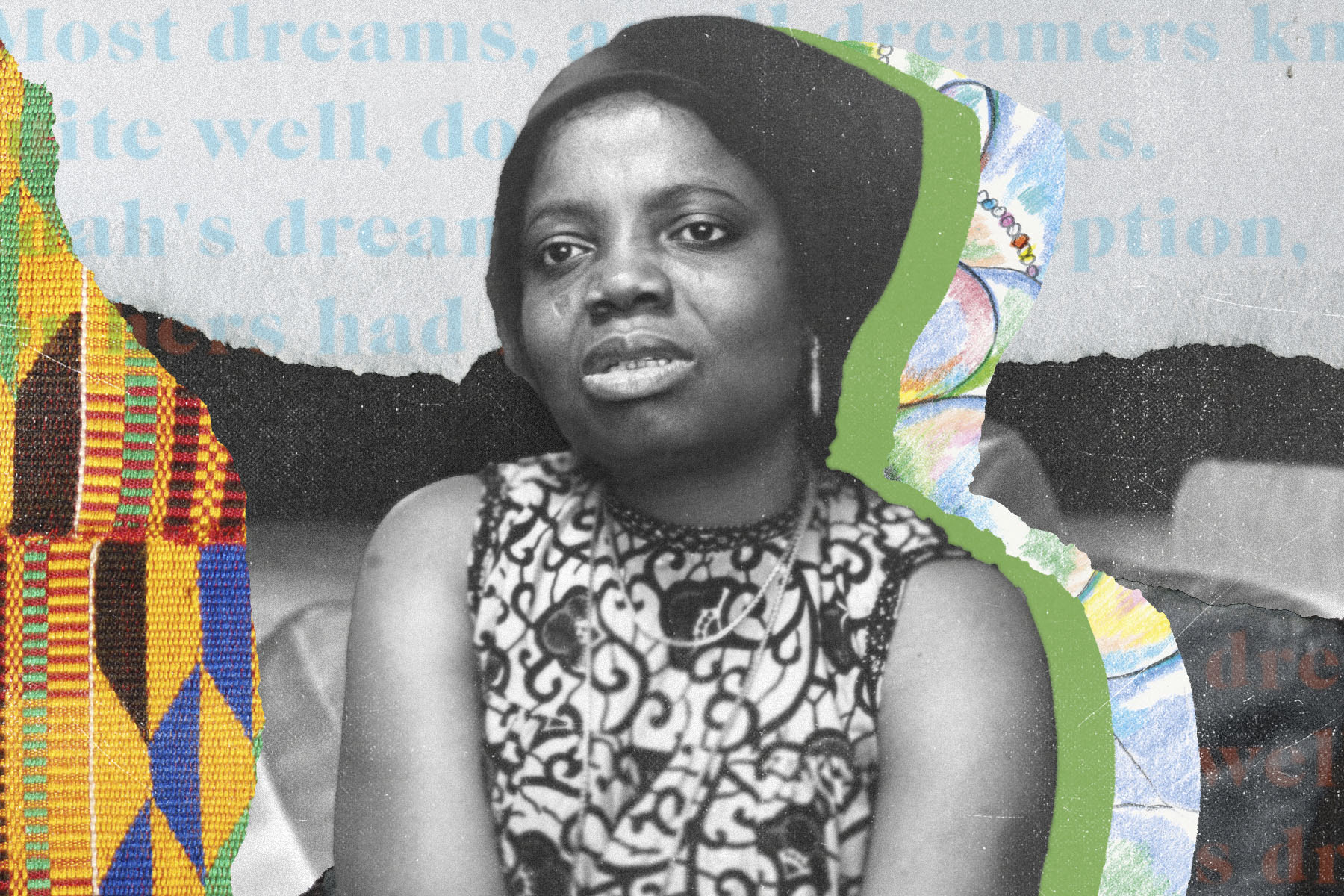

My mother, the pioneer: how Buchi Emecheta captured immigrant life in 1970s London

Nigerian author Buchi Emecheta balanced a literary career with raising five children. As a new edition of her seminal novel Second-Class Citizen is released, her son remembers her remarkable career.

There was a side to my mother which was a stranger to me. This was The Writer – Buchi Emecheta, the public figure whose name was on the cover of the books she wrote and who led a separate existence beyond the personal relationships with her in the family. I first encountered her aged eleven when on returning from school I learned that her first novel In The Ditch, had just been published. That her scribblings were now a proper book like those in the library, was amazing to us in itself, but as soon as I sat down to read it, I was immediately gripped by the story and even though I knew I was one of its characters, had the disconcerting feeling of having one’s experience objectified in prose and seeing oneself from the outside. To this day I regard it as a gentle masterpiece, one of the best social documentary novels of that type that I have ever encountered.

My mother wanted to be a writer from a very early age, but as an orphaned teenager from an impoverished family it was not something she dared to openly admit. She came of age in the 1950s, in pre-independence Nigeria. As a scholarship girl, she was educated by white Ma'ams in a boarding school in Lagos. She describes in Second-Class Citizen how a form mistress publicly humiliated her for believing that she could one day be a writer, and later, after moving to London, how her husband rather than supporting her ambition to write, burned her first manuscript. To have proved them wrong in print seems both a validation and a vindication of these painful experiences.

My mother was only 16 when she became pregnant and married, a fact I can still barely comprehend when I look at the monochrome photo taken of her in the Lagos registry office with her future husband (Frances in the book). She arrived in the UK when she was 18 and though she spent most of her subsequent life here, it was Nigeria – particularly the town of Ibusa – that retained a strong presence in her mind. As children we shared this vision because she domesticated it and made it part of our home identity. Growing up in Kentish Town, Ibusa, which we had never visited, was somehow as real to us the slums and council estates in which we lived and which she wrote about so evocatively.

Books were also domestic things. We were poorer than I realised at the time, but we never seemed to lack for books and stories – not just the ones we read and shared, but the ones my mother wrote in front of us at the kitchen table, after supper and when we had gone to bed. She wrote copiously in long hand with barely any corrections, filling exercise book after exercise book, before transcribing everything into manuscript form on an old Olivetti typewriter.

Many of the incidents in Second-Class Citizen I recall vividly, although my perspective was that of a small child. I was unaware, for example, of the implications of the racism that we experienced from neighbours on a daily basis, the domestic abuse of my father, and the intrusive interventions from not always well-meaning social workers and school educators. My mother – still in her early twenties – negotiated all this on her own and still managed to write novels and complete her degree.

It was quite a task and that she carried it off when she was so young is remarkable. Was there a downside to all this? With hindsight, possibly. As children, we were deprived of our mother to some extent. Orphaned by her studies and her need to work, we were for some of those years, latchkey children. Later, as she became a public figure and our social situation changed, we had to learn to mediate our personal experiences through the printed version of those events. When I read Second-Class Citizen today, I have to keep reminding myself how young my mother was when these things occurred and that she was an African pragmatist who responded to events as she found them and always did what she felt was best for us.

My mother’s account in her books of her life at that time, of her relations with my father for example, is perhaps selective. But it provides a wonderful glimpse of a remarkable woman at the start of the most creative period of her life, capturing instinctively the tenor of the times and writing it down, diary fashion, in the manner of the story tellers she knew and loved from her home village in Ibusa.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Val Wilmer/Ryan McEachern/Penguin