- Home |

- Search Results |

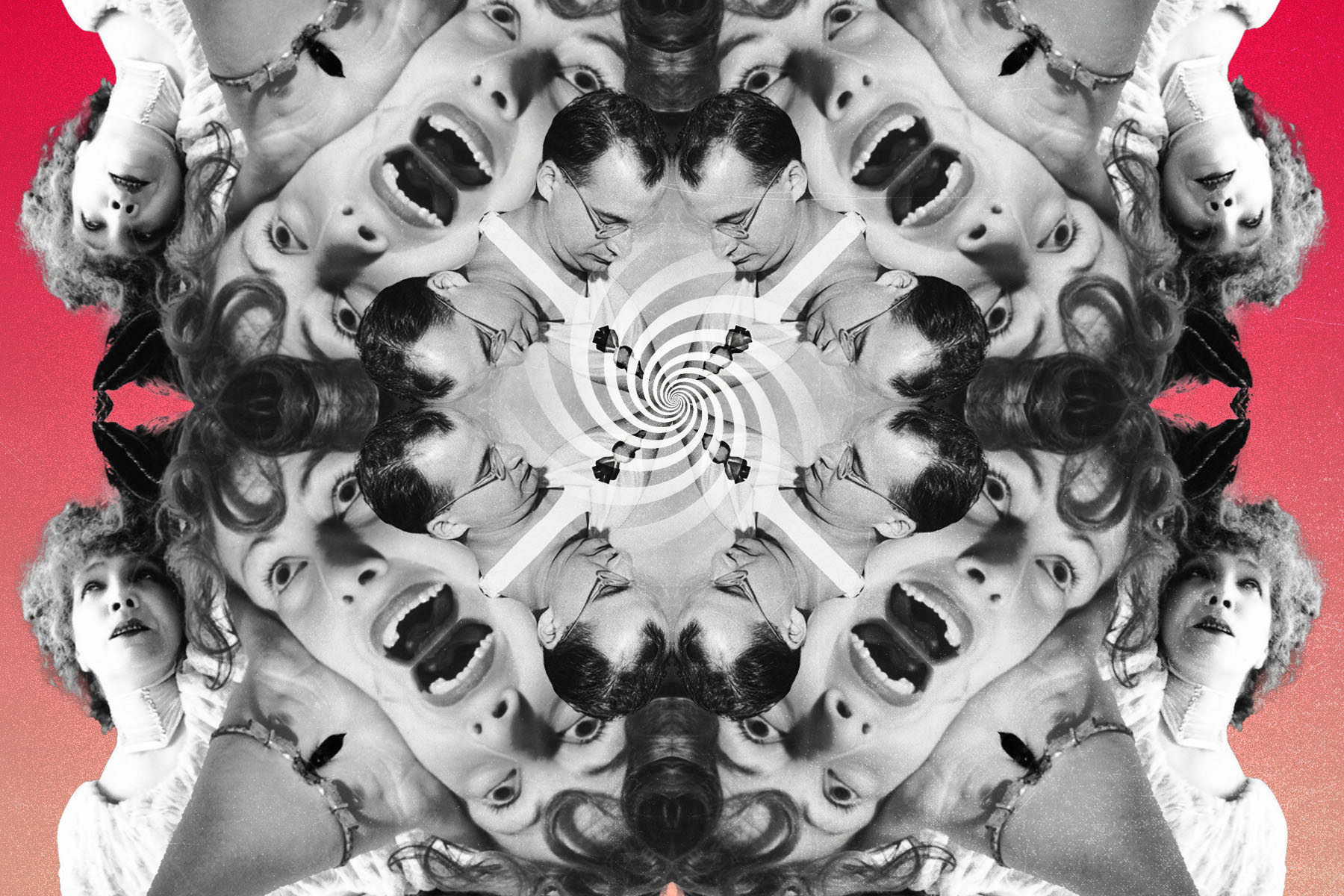

- Why we still love reading about ‘mad’ women

It’s Springtime in Paris, and a group of women are getting ready for a party. Out of boxes they pull sumptuous fabrics trimmed with frills and lace, shrieking with pleasure at the colours, holding the dresses up to see if they’ll fit. But, as Victoria Mas explains in her debut novel (translated by Frank Wynne), The Mad Women’s Ball, this is not a drawing room full of ladies choosing gowns for a gala: the year is 1885, and this is a dormitory of patients at the Salpêtrière, a vast hospital for insane and hysterical women. They’re getting ready for the highlight of their year: The Lenten Ball. For one night only, the hospital gates are thrown open to the public and Paris’ female lunatics are granted their Cinderella moment, expected to beguile and entertain whoever wants to gawp at the madwomen in the city’s metaphorical attic.

It sounds like a fairy tale, but the so-called Madwomen’s Ball is historical fact. I first came across it during one of many hours spent in The British Library researching hysteria for my PhD thesis. I would pour over The Iconography of the Salpêtrière, three tomes that document the invention of hysteria under French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who rose to global fame on the back of his research. Their crumbling pages are filled with photographs of women, faces and bodies contorted by spasms, and endless lists of symptoms that supposedly proved their insanity.

They describe the weekly salons where Charcot would parade his favourite patients in front of the public, using hypnosis and ovarian compression to bring them in and out of hysterical fits (these women became celebrities, had fans and admirers). They mention affairs between doctors and patients, and the extraordinary tradition of the Lenten Ball. Astonished that it isn’t more well known, I’ve often thought about it since and wondered if I’d imagined it. When I read Mas’ novel I was thrilled someone else had come across it.

'These so-called mad women were never a homogenous group of dangerous patients'

Set in the fortnight leading up to the ball, the novel follows a group of women incarcerated at the Salpêtrière. Their names and circumstances are familiar from the Iconography’s case studies, as are details of symptoms and treatments. Mas weaves this information into a compelling work of historical fiction that restores some much-needed humanity to women long reduced to lists of ailments alone.

Take Thérèse, an old sex worker who’s lived in the Salpêtrière for twenty years. She takes care of those younger and sicker than her, knits everyone shawls, and, though perfectly sane, has no desire to leave the hospital – it’s become her home, and what’s on offer for a woman like her out on the streets of Paris is infinitely worse than inside on the ward with its routines and clean sheets.

Not so for teenage Louise, however, a survivor of sexual trauma that left her with hysterical symptoms. She’s preoccupied with the young doctor who tells her he loves her so they can make out, and wants to become the next celebrity hysteric so she can dazzle and marry her beau, then leave the hospital for good. Though new arrival Eugénie shows no signs of madness, she’s been committed by her wealthy father for admitting she can communicate with the dead. Intelligent and inquisitive, her taste for forbidden books and interest in the Spiritualist movement were enough to condemn her to the asylum. Meanwhile their nurse, Geneviève, secretly writes letters to her dead sister.

The stories Mas chooses to focus on drive it home that these so-called mad women were never a homogenous group of dangerous patients who needed separating from society. They were the survivors of trauma, victims of circumstance, or simply inconvenient to the men in their lives. The novel describes a culture invested in repressing women at every turn – be it physically with restrictive corsets, or structurally by affording them no autonomy whatsoever – cloaking its fear in disdain, or worse, faux concern for their wellbeing. These are women driven if not to madness then at least to the asylum by a society obsessed with keeping them in their place: ‘The Salpêtrière is a dumping ground for women who disturb the peace,’ writes Mas.

'These works of fiction are all allegories for how the very real repressive forces of patriarchy drive women mad in the first place'

This is, of course, all very familiar. These are the same social forces that allowed the narrator of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper to be confined to a bedroom for the infernal rest cure by her husband, a doctor; or Mr Rochester to relegate his first wife, Bertha Mason, to the attic at Thornfield Hall in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, leaving him free to shack up with someone else; or Sir Percival Glyde to consign any woman who might stand in the way of his inheritance to an asylum in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White. These works of fiction are all allegories for how the very real repressive forces of patriarchy drive women mad in the first place.

Though it’s not only in literature where this appetite for female dysfunction plays out – where would the modern tabloids be without it? Just as Charcot profited from his weekly lectures, the gossip press has long made its money by contributing to and then documenting the breakdowns of women in the public eye. Britney Spears is the perfect example: hounded by paparazzi until she snapped, then, against her will, placed under a conservatorship by her ‘concerned’ father. Last week she finally gave harrowing testimony, describing thirteen years of subjugation, heavy medication, and relentless observation that would be enough to drive anyone to the edge of sanity. And all supposedly put in place 'for her own good'. Sound familiar? If you’re wondering who would go to a modern-day mad women’s ball, it’s the readers of US Weekly and The Daily Mail’s 'sidebar of shame'.

Why are stories of female madness still so compelling? For some, it’s the grubby voyeurism Mas describes in her novel: "they imagine naked women running through the corridors, banging their heads against tiled walls, spreading their legs to welcome some imaginary lover". But the appetite for these books can also be driven by empathy, and fury at the relentless inequality that still underpins mainstream thinking. Charcot’s original research stated repeatedly that hysteria afflicted men too, but the gendered roots of the word ‘hysteric’ and the fact that he never photographed his male patients mean that detail is often forgotten. There has always been way more scope for masculine madness to be read as genius, or eccentricity. So as long as society remains invested in the policing and shaming of women’s behaviour, whenever we hear stories about supposedly mad women, we’d do well to remember that a synonym for mad is angry.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Ryan MacEachern / Penguin