- Home |

- Search Results |

- Why you should always read the epigraph

A quick literary teaser: who is the first character we meet in The Great Gatsby?

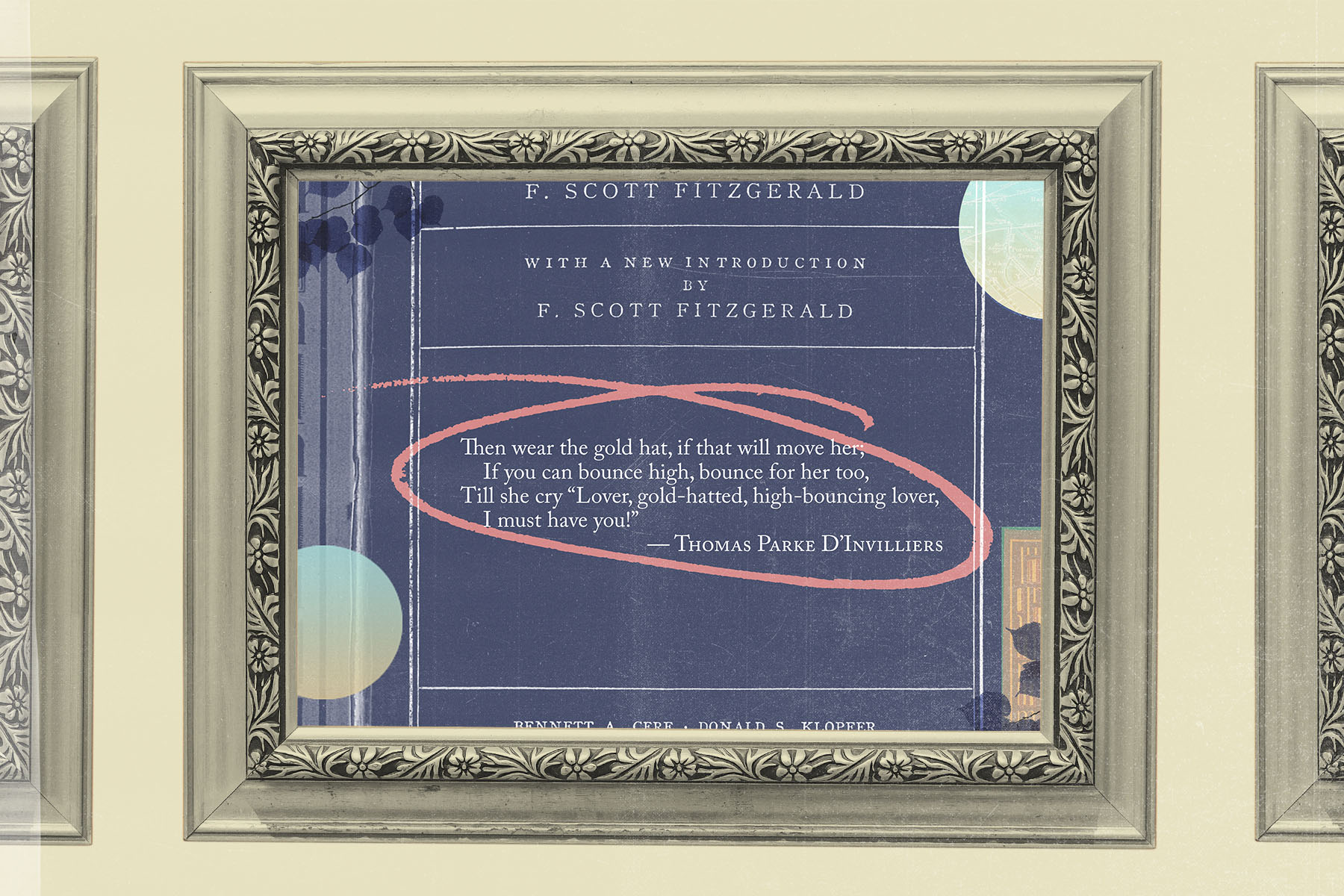

If you said Nick Carraway, then you’re only half right. You could argue it’s Thomas Parke D’Invilliers, the poet who coined the lines that form the novel’s epigraph:

"Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry ‘Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!"

At first glance, the poem seems to offer a straightforward piece of advice. It fits with the Jay Gatsby we come to know, who is wealthy, showy and desperate to win back his love interest, Daisy.

But Thomas Parke D’Invilliers is not, of course, a real poet. He’s a character in Fitzgerald’s debut novel, This Side of Paradise, a poet described by the novel’s main protagonist, Amory, as an ‘awful highbrow … a blighted Shelley, changing, shifting, clever, unscrupulous’. In this light, his words look less like advice worth heeding. It is fitting that for the story of Jay Gatsby, with his mysterious background, Fitzgerald chose an epigraph not from one of the go-tos – the Bible, perhaps or Paradise Lost – but from a bad poem written by a pretentious fictional poet.

Some people think of epigraphs as quotations designed, as most dictionary definitions have it, to suggest the ‘theme’ of a work. But that’s a simplistic view – one ironised by Orhan Pamuk through his deliciously playful epigraph to The Black Book: ‘“Never use epigraphs, they kill the mystery in the work!” (Adli).’ A good epigraph can do the opposite: add layers of mystery to a book. And as with The Great Gatsby, a good epigraph rewards digging a little deeper.

'Ignoring the epigraph feels like walking into a restaurant and diving into a 12oz steak'

Not all books have epigraphs, which is maybe why it feels so normal to skip over them, or at least not give them the attention they deserve. But to me, ignoring the epigraph feels like walking into a restaurant and diving into a 12oz steak before you’ve had a chance to take off your coat. You need the preamble: the moment to sit down and catch your breath, the glass of water, the little pot of olives. These motions are a halfway house between the outside world and that of the restaurant. The same goes for epigraphs, which ease you into a book, gently reminding you that you are crossing from one world into another, from the harsh light of reality into bookland.

Since they became popular in western literature in the 18th century, authors have used the epigraph in various imaginative ways. Some writers use them to show their seriousness by yoking their work to the canon. T S Eliot, who believed that poet should write ‘with a feeling [of] the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer’, chose as his epigraph to The Waste Land a quotation from the Satyricon by Gaius Petronius, left in untranslated Latin and Greek.

The best epigraphs, however, are quotations that, freed from their original context and rehabilitated in a different space, can generate enlightening new meanings. In her novel ", Yiyun Li quotes Elizabeth Bishop’s poem Argument:

"…Distance: Remember all that land

beneath the plane

that coastline

of dim beaches deep in sand

stretching indistinguishably

all the way,

all the way to where my reasons end…"

In Bishop’s poem the speaker meditates on the ‘gentle battleground’ of ‘voices’ that take place in an argument. In Li’s novel, however, which takes the form of a beyond-the-grave conversation between the speaker and her dead son, the line ‘where my reasons end’ gathers a heartbreaking significance – a statement of the world’s incomprehensible, reasonless cruelty.

But how do you pick just one quotation from literature’s endless store? Herman Melville decided against making any such choices, and instead introduced Moby-Dick with a wildly varied, mammoth collection of ‘extracts’ that range from the very beginning of creation (‘“And God created great whales” – Genesis’) through Pliny, Shakespeare, Montaigne, Hobbes, and into the realm of American folk songs and contemporary American writers.

George Eliot, too, was such a serial epigraph-user that many of her readers at the time are said to have grown weary of her fondness for the device (each of Middlemarch’s 86 chapters had a separate epigraph). If this behaviour seems excessive, then we might find comfort in Thomas Pynchon, who began part four of Gravity’s Rainbow with the perfectly postmodern, ‘“What?” – Richard Nixon.’

'And sometimes the best epigraphs are the simplest'

A nice halfway house is to include just a few epigraphs – the benefit of which is that they can interact in surprising ways. Ali Smith, in Spring, uses five epigraphs, including a quote from Shakespeare’s Pericles and another from the French philosopher Alain Badiou: "We must begin, which is the point. After Trump, we must begin." The time gap of four centuries years looks stark on the page, but encapsulates Smith’s project, which is to marry the old and the new, tackling the 21st-century upheavals of Brexit and Trump through a riff on the story of Pericles.

And sometimes the best epigraphs are the simplest. In her Booker Prize-winning The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy chooses a quotation from John Berger’s novel Q: "Never again will a single story be told as though it's the only one." It’s a poignant opening to a book that delves into the psyches of several characters between different time periods, and a nod to Roy’s purpose: to tell a fresh story about the caste system in postcolonial India.

Miguel de Cervantes began Don Quixote by writing (in his preface, ironically): ‘My wish would be simply to present it to thee plain and unadorned, without any embellishment of preface or uncountable muster of customary sonnets, epigrams, and eulogies, such as are commonly put at the beginning of books.’ At their best, epigraphs can be funny, surprising, depressing, clever and profound. Far be it from me to take issue with Cervantes, but I’d say he was missing a trick.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Ryan McEachern / Penguin