- Home |

- Search Results |

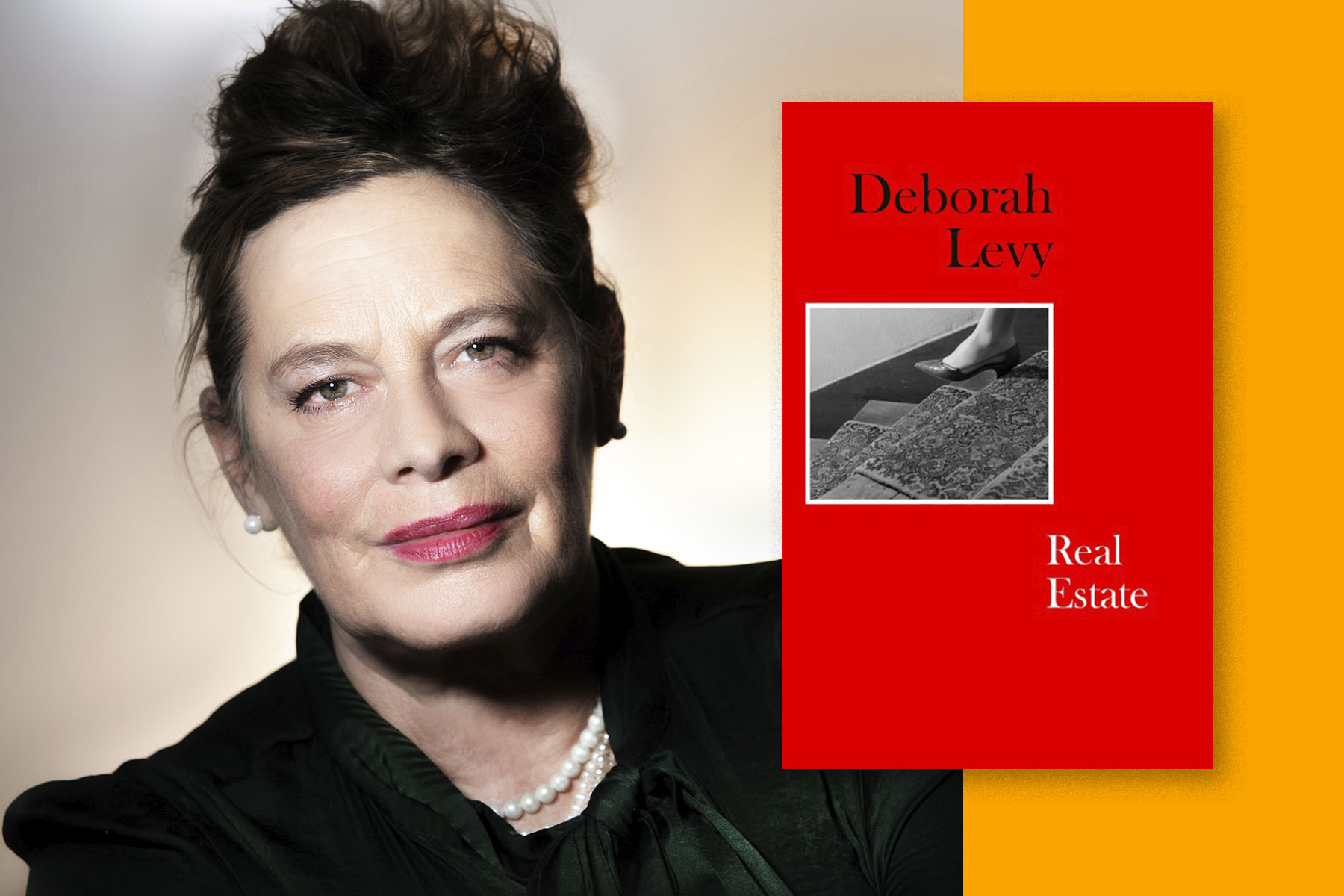

- Deborah Levy on the art of living

Deborah Levy on the art of living

Real Estate concludes the Booker-shortlisted author's celebrated trilogy of 'living autobiographies'. Here she reflects on their innovations of style, learning from Virginia Woolf and what makes for a good life.

I always find, after finishing a book by Deborah Levy, certain details linger, like leaves caught on your coat after a long walk. In Swimming Home, the novel she published in 2011 after a lengthy hiatus, which won Levy a first Booker shortlist and a legion of new readers, it was the “sky smashing against the mountains” as Kitty and Joe sit in an orchard on the cusp of their devastating affair. In 2019’s longlisted The Man Who Saw Everything, it was a cluster of damp mushrooms, shining dully with rain, which elicit lovers Walter and Saul stand over with their heads pressed quietly together.

In new book Real Estate, the third instalment of Levy’s “working autobiographies” which began with 2014’s Things I Don’t Want to Know and continued with The Cost of Living (2018), it is an ostrich egg-shaped fireplace that we encounter in the book’s opening pages; not the most sensual detail in a book abundant with them, but one the narrator immediately adds to her fantasy home. It sets up a central theme: how do we reconcile the gap between the life we imagine for ourselves, and the one reality offers us?

The autobiography project began, as the subtitle to Things I Don’t Want to Know tells us, as a response to George Orwell’s 1946 essay ‘Why I Write’. But it quickly evolved into a structural experiment of its own, as Levy’s writing often does (her most recent novel, The Man Who Saw Everything – written in the time Real Estate is set – plays with memory and bends time to its will).

"I began to find a voice that was intimate, but also formal – that was very important to me," she tells me, over Zoom early one morning in May. "I discovered something about chronology, which is that most conventional autobiographical writing starts with childhood. But I realised that I didn't have to start there. I wanted to shake that sort of dusty notion of autobiographical writing."

Although the three books cover major events in Levy’s life – fleeing the political violence of South Africa for London as a child, the breakdown of her marriage in her fifties, the blossoming of late career success – the narrative slips back and forth in time, leaves great swathes of her story out and measures out details with a novelist’s eye.

The trilogy is also in unfussy communication with a wide range of authors, and one of the joys the books offer is an insight into novels, music and films that have shaped Levy’s life. If Orwell is the background presence of book one, Virginia Woolf – in particular A Room of One’s Own – hovers time and again over Real Estate, right up to its final passages.

“Woolf found that very calm, intimate voice,” Levy says. “But I knew as a reader that she was enraged. I thought about that quite a lot: the clear, economic, paired-down prose that comes when you struggle very hard with something complex and come up the other side with something that feels as truthful as you can.”

The controlled rage in Woolf’s appeal for domestic space in which women can write freely is carried on, in Real Estate, as an often-pithy plea for cultural space. We see the narrator patronised horribly by an unnamed male author at a literary event, have dispiriting discussions about “female leads” with movie executives. At one point, musing with a friend over a script she would write for Bette Davies or Joan Crawford in their later years, she says: “Give her loneliness. Even better, give her a critique of her loneliness. Give her desires and conflicts that are not all about men. Give her melancholy rather than depression, sadness rather than despair.”

'In this way, these book are my most political writing.'

The trilogy has been embraced by Levy’s admirers as a “manifesto” (in the Financial Times); as welcome for the wisdom they offer on motherhood, friendship and professional success as they are for the vivid and satisfying prose. It is role she says she is not uncomfortable with.

“Because I’ve learned so much from books,” she explains. “Books are made for life. And the narrator of all three of these books is herself learning on the hop. That’s how it should be.” As way of evidence, she holds up a copy resting next to her laptop of Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin: “I am reading it for the fifth time, and I learn from it every time.”

I wonder if offering a glimpse, however literary in poise, into her personal life has changed Levy’s relationship with her readers.

“It's a different project altogether,” she agrees. “In novels, characters are my avatars, right? They argue for me and embody my thoughts. But in the living autobiographies – which is just a term I made up – the challenge was not to take a fixed position on my opinions of life, but have a whole lot of things coexist together: rage, strength, vulnerability, humour, confusion, clarity.

“I think there is this idea that a female character, or narrator, has to have one clear thought or motivation. And that's something I feel strongly about: why not be all those things at once, why not feel your feelings and walk into the world with them and see what happens. It occurred to me that, in this way, these book are my most political writing.”

She is looking forward to finding out what readers make of the final part, but concedes the project has already led to some new experiences.

“I was out and about on my bicycle and someone waved at me,” she smiles. “And I thought: oh, I didn't know that person. And then I realised that they have read my book. And it's a very warm feeling.”

'Of all the arts, the art of living is the most important'

Another moment that stuck to me from Real Estate occurs around halfway through, when the narrator is eating lunch with a younger colleague while on a residency in Paris – passages which, incidentally, match some of Baldwin’s magic for depicting the City of Lights. "Of all the arts," Levy writes, "the art of living is probably the most important, something at which he was especially skilled."

It is a passing observation about a minor character, but it also felt like a hint at what the trilogy is striving for: not, as she says in book two, an attempt to "cover the past in dust sheets" but a depiction of life in practice.

"That has to be the most important art, doesn't it?" she says. "I mean, it would be really sad to be very bad at living. I don't want to make a claim on what it means for anyone else, but for me it's about human attachment, being able to live warmly with each other. It's about breaking bread with strangers around the table. It's about finding a way of living that feels more right than wrong; not necessarily having to live the societal script that has been written for any of us.

"It’s sitting on a bus, picturing a scenario that makes us feel happier and thinking: how can I bring that a little bit nearer to my life?"

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.