- Home |

- Search Results |

- How a once-banned Japanese children’s book became a classic – and the next Studio Ghibli film

How a once-banned Japanese children’s book became a classic – and the next Studio Ghibli film

Genzaburō Yoshino’s life-affirming novel How Do You Live? is being adapted to screen by legendary film director Hayao Miyazaki. We take a look at its timeless appeal and subversive past.

Technically speaking, the bestselling Japanese book of 2018 was written over 80 years earlier.

That year, Shōichi Haga’s manga adaptation of How Do You Live? sold more copies – a whopping two million – than any other Japanese book. The original, a children’s novel first published in 1937 by Genzaburō Yoshino, was a top 10 bestseller that year as well, adding to the millions of copies it has sold since its release.

Their combined success wasn’t altogether surprising. Today, Yoshino’s How Do You Live? is an essential part of a Japanese classical arts education, and the announcement in 2016 that director Hayao Miyazaki was coming out of retirement to turn it into the next film for Studio Ghibli – the world-renowned studio responsible for a swath of critically acclaimed animated films including the Oscar-winning Spirited Away – was enough to spur sales of both the book’s new manga adaptation and the 1937 original. This month, an English translation of the beloved Japanese classic is being published for the first time ever by Rider Books.

Yet, the book almost didn’t survive the Second World War – and in fact, almost never existed to begin with.

In fact, 'How Do You Live?' almost never existed to begin with

In the interwar period of the 1920s and 30s, Japan was becoming increasingly militaristic and authoritarian. In Tokyo, where How Do You Live? is set, the government had created a special branch of the police, called the Tokkō, to uphold the Public Security Preservation Law, meant to squash any anti-authoritarian, perniciously Western ideas expressed in art, writing, speech or performance.

By the early 1930s, when he was 30 years old, the Tokyo-born Genzaburo Yoshino had enrolled at Tokyo Imperial University to study economics but graduated with a philosophy and literature degree. He then found work at the University of Tokyo library, where he became interested in politics and began to explore socialism. By 1931, he was imprisoned for 18 months for his involvement in socialist thinking.

Yoshino’s time in prison would strengthen his idealism. Upon his release, he was invited to work with Japanese novelist and playwright Yūzō Yamamoto at Iwanami Shoten Publishers, where he was tasked with writing the last entry in a series of books that can be loosely translated to ‘The Japan Young People’s Library’.

The book was originally supposed to be an ethics textbook; the idealistic Yoshino wanted to teach future generations of Japanese children the importance of humanities and of thinking for yourself. Knowing that these kinds of ideas were anathema to the Tokkō, Yamamoto suggested he make it a novel instead.

“For me,” argues Bruno Navasky, the translator for the book’s first English-language edition, “the strong thread informing this book was an experience of an oppressive, dictatorial, even fascistic government. Yoshino and Yamamoto were both intellectuals with progressive, political inclinations, who were imprisoned for what they thought and said.”

The Tokkō, known colloquially at the time as the thought police, were very interested in tracking people like them down.

“It’s part of the reason that How Do You Live? is a novel; writers were being imprisoned right and left for what they wrote, and for very mild expressions of individuality and conscience, so there was a deliberate choice to fly under the radar and write this series for children. It seems to have worked.”

Or at least it did for a time – by 1942, the Japanese censors had cottoned onto it and the book was taken out of circulation. When it was republished in 1945, immediately after the War, the book had been “washed clean” for children. Mentions of imperialism and criticism of capitalism and unpatriotic behaviour were cut from the book, as were references to the problems of class.

“It wasn’t until later that it was republished in its original version, which would have appealed to adults, too,” Navasky explains. That era of censorship was constantly on his mind as he translated the original text for today’s English readers.

“I think it deeply resonates with this upsurge in that kind of government today,” he says. “When I was working on this book, I didn’t know that Trump was going to be a one-term president; most Americans felt a deep uncertainty about which way that seesaw was going to tip. And of course there have been recent dictatorships in Turkey, Indonesia, North Korea. So I was kind of thinking about how to stand up for what you believe in, and how to decide what’s right, basic ethics – which is how this book was born. That kind of thinking seemed very necessary in this book, to me.”

Ironically, Navasky says that it is the of-its-moment nature of How Do You Live? that helps the book transcend time.

“The particular 1930s Japanese context led Yoshino to put emphasis on individual thinking in a way that I think we take for granted in the West during the modern era – and it never hurts to have that re-examined, either.”

If these themes seem strikingly mature for a children’s book, that’s because they are. “The text I worked with was the original text, with none of the deletions. In general, it’s a book with a real identity crisis: is it a book for older readers or younger readers? That’s the conundrum of it.”

'I was thinking about how to stand up for what you believe in, and how to decide what’s right, basic ethics – which is how this book was born'

There are arguably more adult precedents in the English-language canon for How Do You Live? than children’s ones, though even these are few and far between: structurally, the aforementioned Moby-Dick is a relative; thematically, Sheila Heti’s 2012 masterwork How Should a Person Be?, a work of auto-fiction that explores how to make a meaningful creative life, comes closest. Part of the enduring charm and utility of Yoshino’s book is that it remains a relevant guide to leading a culturally enriching life.

Navasky agrees: “I think it’s that, and it’s a record of its time – and, for a book that at least on one level is aimed at younger readers, it goes very deeply into the mechanics and the philosophy of how to lead one’s life. And what it means to be a human being. I came to love and deeply respect this book for doing all of these things simultaneously.”

It’s part of the reason the book has survived until now, and it’s likely a significant part of why it caught the attention of Hayao Miyazaki – and pulled him out of retirement in order to construct a film around it.

“When I talk to older Japanese people now, most of them know the title. But there’s the influence that Miyazaki says it had on him – it may have been like something passed down by word of mouth and generations, parents to children. Those who liked it, loved it.”

The forthcoming film’s producer, Toshio Suzuki, said that Miyazaki is working on the film for his grandson as his way of saying “Grandpa is moving onto the next world soon but he is leaving behind this film.”

What this will mean for the book in the future, Navasky says, remains up in the air.

“Miyazaki’s movie reportedly won’t be the book; it will be the story of a boy who reads the book, which gives the director a lot of leeway to make it a movie for everyone. There will be a lot of interest, afterward, in knowing what the source material looked like, and I’m deeply curious about what this book will mean to them.”

Navasky feels certain “that it speaks to our time, in terms of the politics of the book”, but beyond that, he says, it’s a mystery.

“A book like this is meant for a special reader.”

What did you think of this article? Let us know by emailing us at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk.

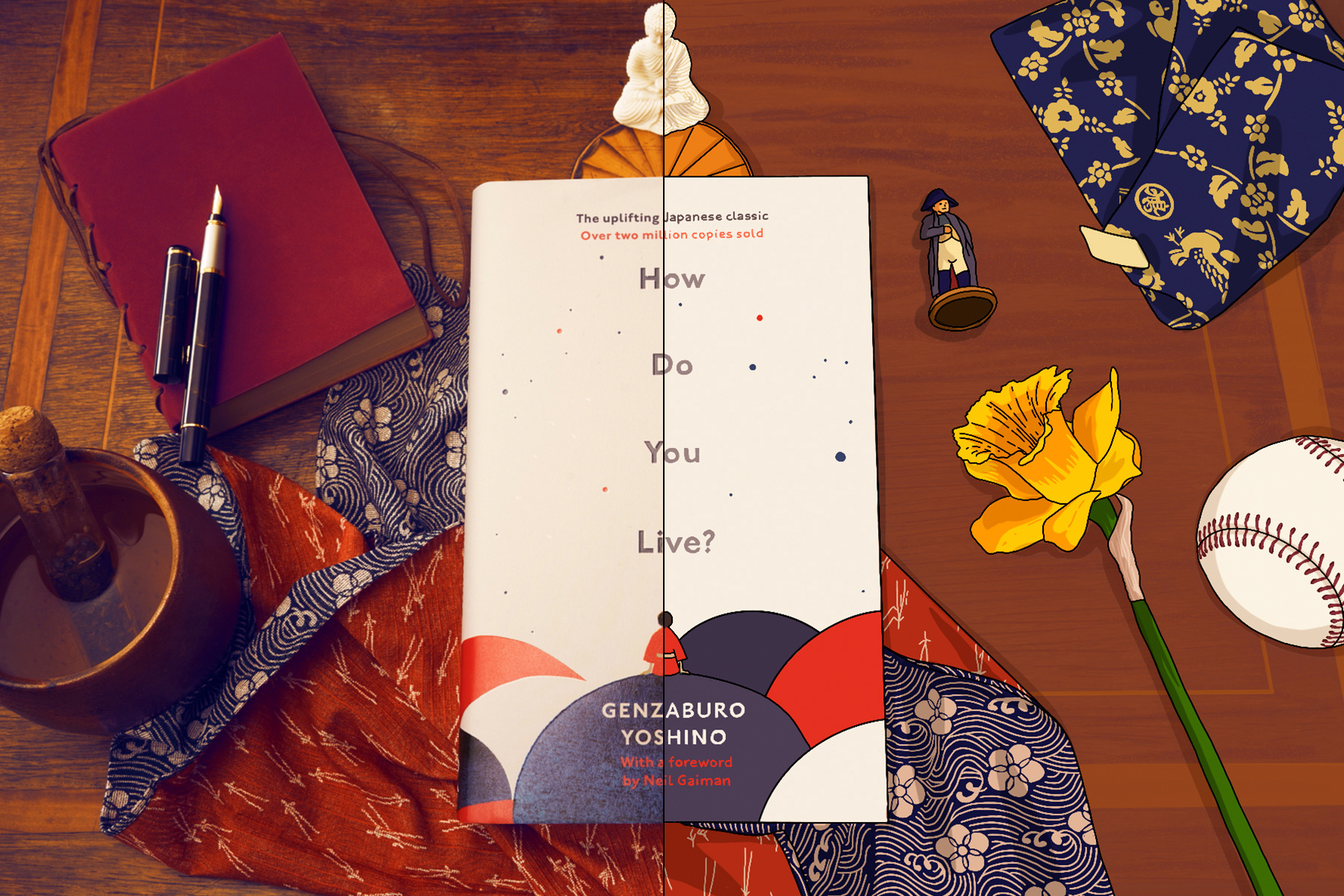

Photos: Stuart Simpson / Penguin

Illustration: Mica Murphy / Penguin