- Home |

- Search Results |

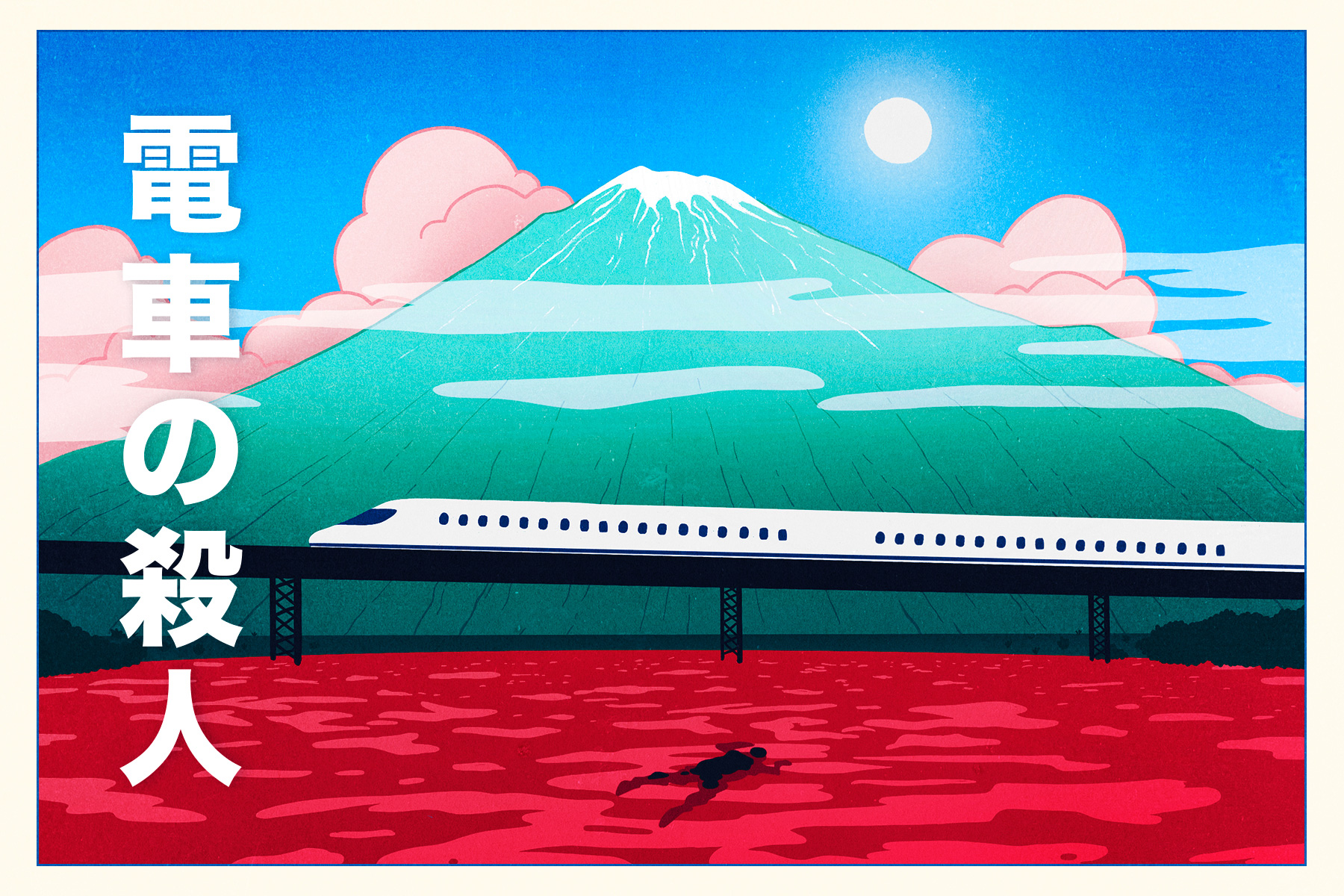

- From the Orient Express to Bullet Train: why crime loves a locomotive

From the Orient Express to Bullet Train: why crime loves a locomotive

Kōtarō Isaka’s thriller Bullet Train became a runaway success in Japan and is now a feature film starring Brad Pitt and Sandra Bullock. It is the latest, Jake Kerridge explains, in a long line of crime books set on the sleepers.

Have you ever looked at the person sitting opposite you on a train and wondered if they might be a murderer? I’m betting that thousands of Japanese commuters are doing just that every day, following the huge success of Kōtarō Isaka’s bestselling thriller, Bullet Train.

In this novel – which takes place in real time on a Shinkansen bullet train travelling from Tokyo to Morioka – every other passenger seems to be a killer. They range from Satoshi, a ruthless psychopath with the appearance of a cherubic schoolboy, to professional hitman Tangerine and his eccentric sidekick Lemon, who has a penchant for quoting lines from the Thomas the Tank Engine books.

As the various killers compete to get hold of a suitcaseful of money, it soon becomes clear that not all of them will survive as far as Morioka. Like all the great train-based thrillers, the novel combines an exhilarating sense of forward momentum with the creepy claustrophobia that comes from being stuffed cheek by jowl with a load of strangers in a confined space. (There’s a very funny scene in which two of the killers are obliged, owing to lack of elbow room, to partake in their first ever sit-down fist fight).

Bullet Train is published in English translation this week, and a film version starring Brad Pitt and Lady Gaga is in production. Both novel and film are likely to be international hits: there’s something uniquely potent about the combination of trains and crime.

Christie was fascinated by the Orient Express - on one occasion she slipped off the platform and fell in front of it

A friend of mine who works in London says that nothing thrills her more than leaving early enough to return home to Maidenhead on the 4.50 from Paddington, the train immortalised in the title of one of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple mysteries. She claims to spend the journey staring out of the window in the hope of witnessing a murder on a passing train, as Mrs McGillicuddy does in that novel – a testament to the way in which train-based mysteries get under our skin.

The most famous train mystery, still a bestseller after nearly 80 years, is Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934). Christie was fascinated by the Orient Express, often seeing it at Calais when she was travelling into Europe and going to gaze at it; on one occasion she slipped off the platform and fell in front of it (“Luckily a porter was at hand to fish her up before [it] started moving”, recalled her husband).

She cannily knew that her readers would also want to get up close to the world’s most luxurious train – albeit vicariously – as did Ian Fleming, who put James Bond on board in From Russia, with Love (1957). Graham Greene also used the Orient Express as the setting for his early thriller Stamboul Train (1932) – although unlike Christie and Fleming he had not been able to travel on it himself, so while writing the book he would get in the mood by playing Arthur Honegger’s Pacific 231, an orchestral work that mimics the sound of a steam train, over and over on his gramophone.

'One of the remarkable characteristics of Japanese railway mystery stories is the frequent use of alibis based on accurate timetables'

There’s more to the appeal of the train thriller than glamour, however, and ordinary trains have long been a staple of crime fiction. An early example is H F Wood’s The Passenger from Scotland Yard (1888): it has an even smaller circle of suspects than Murder on the Orient Express, with a man being killed in a locked compartment containing four other people.

Victor Whitechurch introduced the first “Railway detective”, Thorpe Hazell, in Thrilling Stories of the Railway (1912); Hazell’s knowledge of the technicalities of railway signalling is often a key asset in his thwarting of various kidnappers, thieves and spies. The greatest of the early train crime writers, however, was Freeman Wills Crofts, a railway engineer whose murder mysteries often obliged readers to retain in their heads complicated details of train timetables on which the suspects’ alibis depended.

Crofts was particularly influential in Japan, where a tradition of railway mysteries took hold of which Kōtarō Isaka’s Bullet Train is the latest example. Notable books in this field are Seicho Matsumoto’s Points and Lines (1958) – the author hired a room in the Tokyo Station Hotel to write it in – and Yu Aoi’s The Tragedy of the Funatomi (1936). “One of the remarkable characteristics of Japanese railway mystery stories is the frequent use of alibis based on … accurate timetables,” the railway journalist Takayuki Haraguchi – author of The Genealogy of Railway Mysteries – has said. Of Yu Aoi’s book he has noted: “I actually compared a timetable used at that time with the novel and could not help getting excited at the precise plot based on a real railway timetable.”

Apart from the intricacies of timetables, train-based crime novels grip because they offer an opportunity for the author to throw characters together who might otherwise never have a chance to mix. Where else would there be the time and level of intimacy for two strangers to fall into conversation and make a pact to each murder the person who is ruining the other’s life – the premise of Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950)?

My favourite train-based crime novel has to be Ethel Lina White’s The Wheel Spins (1936) – now better-known under the title of Hitchcock’s film version, The Lady Vanishes – in which young socialite Iris Carr befriends a middle-aged governess, Miss Froy, on a train, only for Miss Froy then to disappear and the other passengers to claim that no such woman was ever on board. The book is memorable not just because of its suspense – you can almost hear the urgent clickety-clack of the train in the background as Iris races to discover who has abducted Miss Froy before the train reaches its destination – but also because of the cast of passengers who all have their own private reasons either to help or hinder Iris’s quest.

With their large casts drawn from various strata of society, railway mysteries often serve as a good introduction to other cultures – for example, Baksho Rahashya (Incident on the Kalka Mail) by Satyajit Ray is a vibrant portrait of 1970s India. And for much the same reason today’s writers of historical crime fiction often use railways settings – see Andrew Martin’s series set in Edwardian England and featuring the “Steam Detective” Jim Stringer, or Edward Marston’s books about the Victorian Railway Detective Inspector Colbeck.

The 10.35 to Euston may seem a long way from the Orient Express, but like all the great train thrillers it reminds us that you can find all human life on board a train

But although today’s commuter trains might seem like dull settings for novels compared with the steam-powered glories of the past, some writers have been inspired by them. Paula Hawkins’s phenomenal hit The Girl on the Train (2015) features a woman who becomes rather too heavily invested in the lives of the people she glimpses through the train window every day; when I asked somebody who worked on the book why it had been so successful, she said it was simply because so many readers could relate to the central character, as we let our minds wander as a way to cope with the daily commute.

I can also recommend The Silence Between Breaths by Cath Staincliffe (2016), which weaves in and out of the thoughts of various passengers on the 10.35 am from Manchester Piccadilly to London Euston. Part of the book’s appeal is that it lets us have a glimpse behind the impassive facades of our fellow commuters as they reflect on their quotidian concerns. But it eventually becomes clear that the passengers will have to connect and unite, as it emerges that one of them is a terrorist with a bomb in his rucksack.

The 10.35 to Euston may seem a long way from the Orient Express, but like all the great train thrillers it reminds us that you can find all human life on board a train – something most of us shut our eyes and ears to when we grumpily hunker down on the commute. So whether you’re an avid trainspotter or just a student of human nature, there’s a railway thriller out there for you. Choo-choo!

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Mica Murphy / Penguin