- Home |

- Search Results |

- How I wrote it: Hafsa Zayyan on We Are All Birds of Uganda

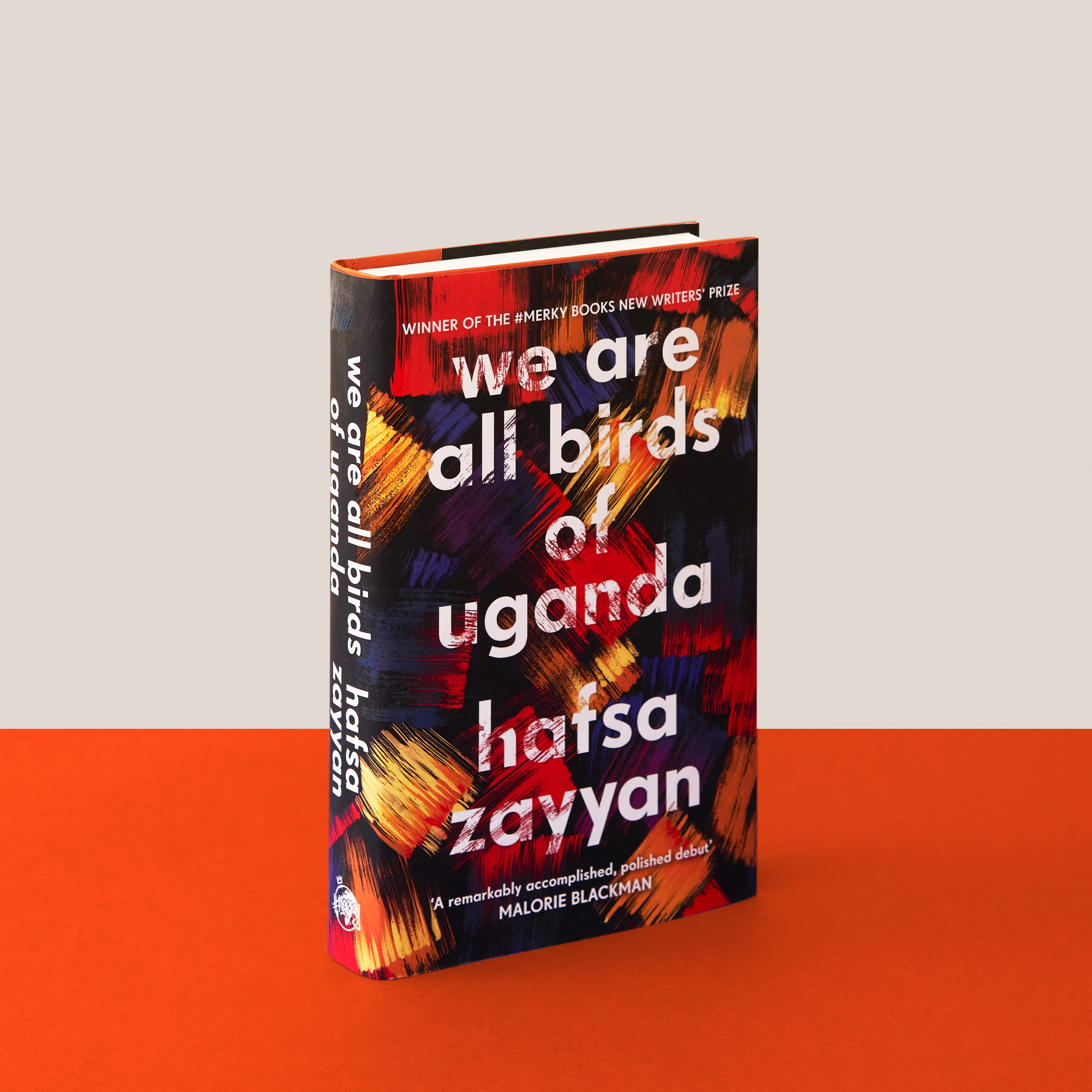

How I wrote it: Hafsa Zayyan on We Are All Birds of Uganda

Hafsa Zayyan managed to write her debut novel in six months, while working full time as a lawyer. Here the winner of the Merky Books New Writer’s Prize discusses the hours of research and late nights it took to produce her brilliant first book.

Weeks after publishing her debut novel, Hafsa Zayyan still considers her career as an author to be something “random and flukey”. The 29-year-old won a publishing contract after entering the first New Writer’s Prize from Merky Books on something of a whim, and ended up having to deliver an entire manuscript in six months – while working full-time as a dispute resolution lawyer.

Nevertheless, We Are All Birds of Uganda is a thing of beauty: an ambitious first novel that spans decades and continents, with two twisting love stories at its core. Tackling issues of identity, religion and colonialism, Zayyan's story explores the legacy of Idi Amin’s expulsion of thousands of people of South Asian heritage from Uganda in 1972. Here, she tells us how she wrote it.

Before your novel, did you write often?

Ever since childhood I’d enjoyed writing short stories, and I wanted, always, to maybe write a book, but I never considered it seriously as a sole career option. I kind of saw writing in the same way that I saw acting or singing, anything that you would maybe have to be a little bit lucky to get your break. In my family, it seemed to be a more secure option to go for an established professional career and degree, and I was interested in the law anyway. So I went and did a university degree in law, then a masters, then I got a job working in the City. And I’ve been there ever since. I did some creative writing at university, but after being rejected by agents with a children’s book I wrote during my holidays I gave up.

How did you come across the prize?

I had been listening to Stormzy for a while and following what he’d been doing, because he’d been doing lots of unusual stuff for a grime artist. So I went to the Barbican and the launch of Merky Books and Rise Up, and heard about the competition and thought, well, why not? Just apply. You only have to write 2,500 words and it’s a wonderful opportunity for you to exercise this part of your brain that’s been dusty completely unattended to for years.

How did you settle upon the subject of your novel?

The prize encouraged entrants to write stories that weren’t being told, that you hadn’t heard people talking about. The 1972 Ugandan-Asian expulsion was something I had only learned about in the past five years, despite it being a massive part of British Colonial and African industry. The idea of someone being able to just expel tens of thousands of people who had been living there, some for multiple generations, and that had happened in the Seventies, not even 100 years ago, and I had no idea. It seemed to have been erased from history. I thought, well, this is a good idea.

What happened next?

I wrote one of Hassan’s letters, the first one, for the competition entry [the letters form the historical part of We Are All Birds of Uganda, and date from 1945 to 1981] and even for that the research was extensive. I went to the British Library to read academic texts on the experiences of refugees on multicultural Britain, and various other text books and memoirs and literature about the Ugandan/Asian expulsion specifically. I wasn’t expecting anything to come of it, not in the slightest.

A month passed and I was shortlisted, and I was asked by Merky to submit the rest of my manuscript within seven days – and I had absolutely nothing. So I had to bash out as much as I possibly could! I think I did another Hassan chapter, because I didn’t have the time to research more of his story, and a couple of Sameer chapters [Sameer is a 20-something lawyer living in modern-day London]. It was like, 20,000 words – definitely not the real novel. And that’s what they judged it on.

When I won, they asked if I could submit the full manuscript by December. At this point, it was June. So I was like, “I guess, I’ll try?”

How, practically, did you balance your full-time job with writing a novel?

I look back at that period of my life and it’s a complete blur. I can barely remember it because I was in a hole writing, whatever, whenever I could. I made a lot of sacrifices socially and I cancelled going on holiday, taking the time off to write.

My hours as a lawyer vary but you can, in lawyer-terms, have a life: you won’t be working that many weekends or late at night. Monday to Friday, if I finished work by 6pm, I’d run to the British Library and read until they closed at 8pm. Then I’d run back home and write as much as I could until midnight. If I didn’t get out at six then I’d be writing 9-11, 9 to midnight, or 10 to 12. I’d basically squeeze it in when I could, and it would be completely fine with me if I only wrote about two or three paragraphs. I didn’t have targets, to meet certain numbers of words or chapters by a specific time, I just did what I could when I could.

Did you encounter any writer’s block?

When I did, I would just read instead, stuff for the Hassan chapters. I was quite disciplined about researching; I felt the responsibility to get it as right as possible, because even though it’s fiction, I wanted the historical elements of it to be as accurate as possible. It’s also an educational tool, that’s another purpose of the novel, to teach people about this part of our history. So if I had a creative block I could still do stuff to progress the novel that wasn’t writing.

How did it feel to submit your manuscript?

It was the scariest time. I was just really worried: they had no idea what the plot was going to be, they had no idea where the book was going to go. I think it took them about a week for them to get back to me, and I didn’t receive any updates in between. So for the whole week I was feeling sick, like, what if they hate this, what if it’s terrible, what if I actually can’t write. But thankfully they were extremely complimentary when they got back to me; I’m sure he knew how to talk to vulnerable debut authors whose creative babies are in their hands!

What was it like when people read it for the first time?

The very first non-family review that I got on Goodreads felt so, so good. And I started getting DMs from people being like, “By the way, I read your book and wanted you to know that it really resonated with me”, or “I felt really seen” or, “it felt wonderful to feel represented.” That kind of stuff felt better than any money you could ever earn from writing a book. People reading it and learning something from it. It was the best feeling ever.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.

Image: Stuart Simpson/Penguin