- Home |

- Search Results |

- The enduring legacy of Toni Morrison

A giant of American literature, Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize in 1993 and was best known for her 1988 novel Beloved, which also won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. No wonder Barack Obama said: "Toni Morrison's prose brings us that kind of moral and emotional intensity that few writers ever attempt."

In 2019, we spoke with several writers about the impact and inspiration Morrison has had on their lives and writing. A year on from the great author's death, their comments remain even more pertinent.

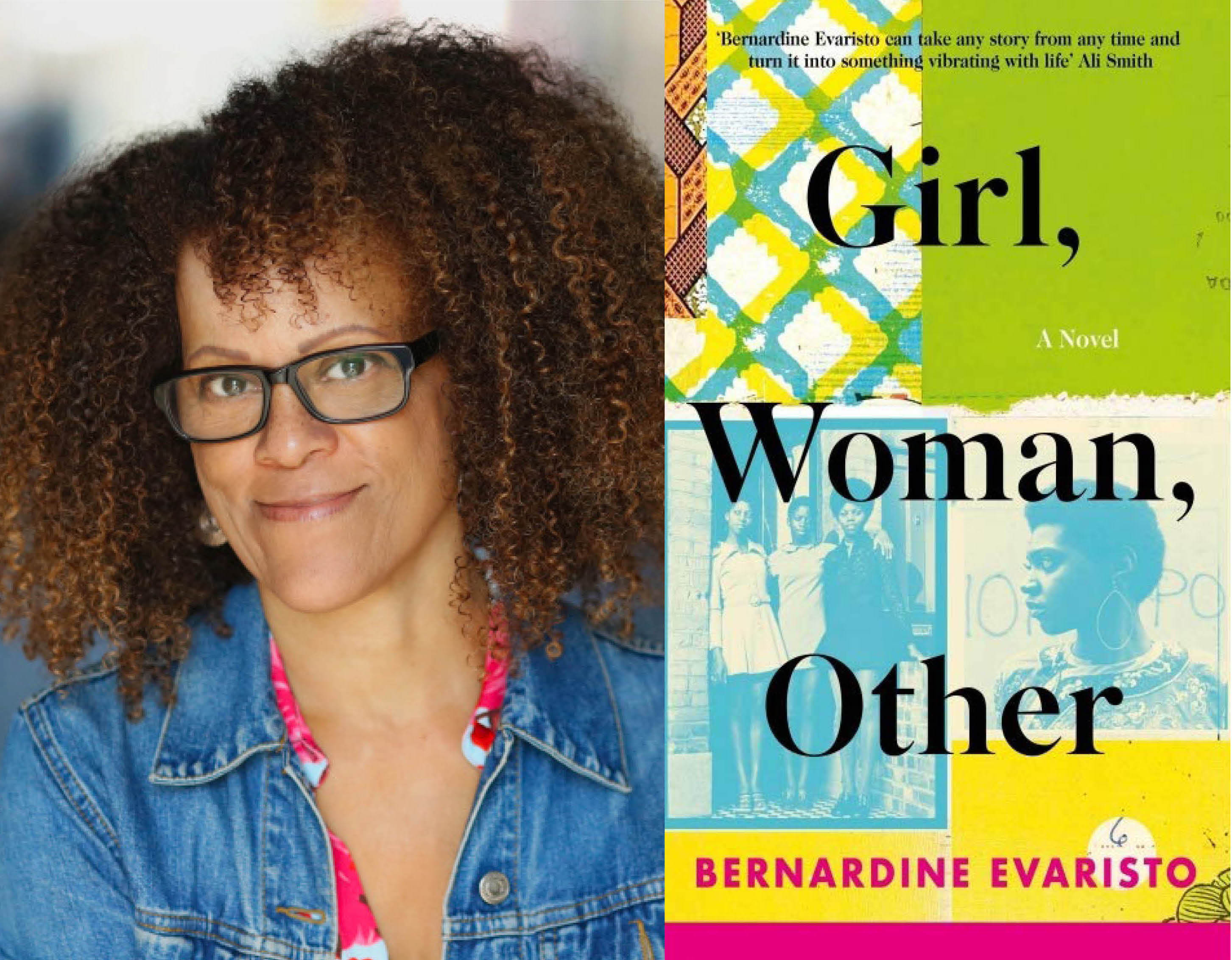

Bernardine Evaristo

In the Eighties I was deeply inspired by the writings of African-American women writers who wrote from that perspective and gave voice to their otherwise absent, marginalised or stereotyped lives in literature. Their works validated my own ambition to write into the almost empty space of Black and multicultural Britain, which I have been doing ever since.

Toni Morrison was the writer I loved the most because she wrote such beautiful, powerful, evocative, complex and finely drawn psychological portraits of African-Americans, especially their women. She is a prose stylist par excellence whose language is as carefully crafted as poetry, so that almost every line of text is quotable. Her novels seem to be written from a place deep inside herself and from deep inside her culture, with an epic and mythic quality. Sadly, nearly 40 years later, there is still very little literature in Britain about our lives, which is why my latest novel, Girl, Woman, Other, imagines 12 different and mostly black female protagonists whose lives intersect.

As much as I adore and want to celebrate Toni Morrison, we must always remember that the African-American experience is not the same as ours.

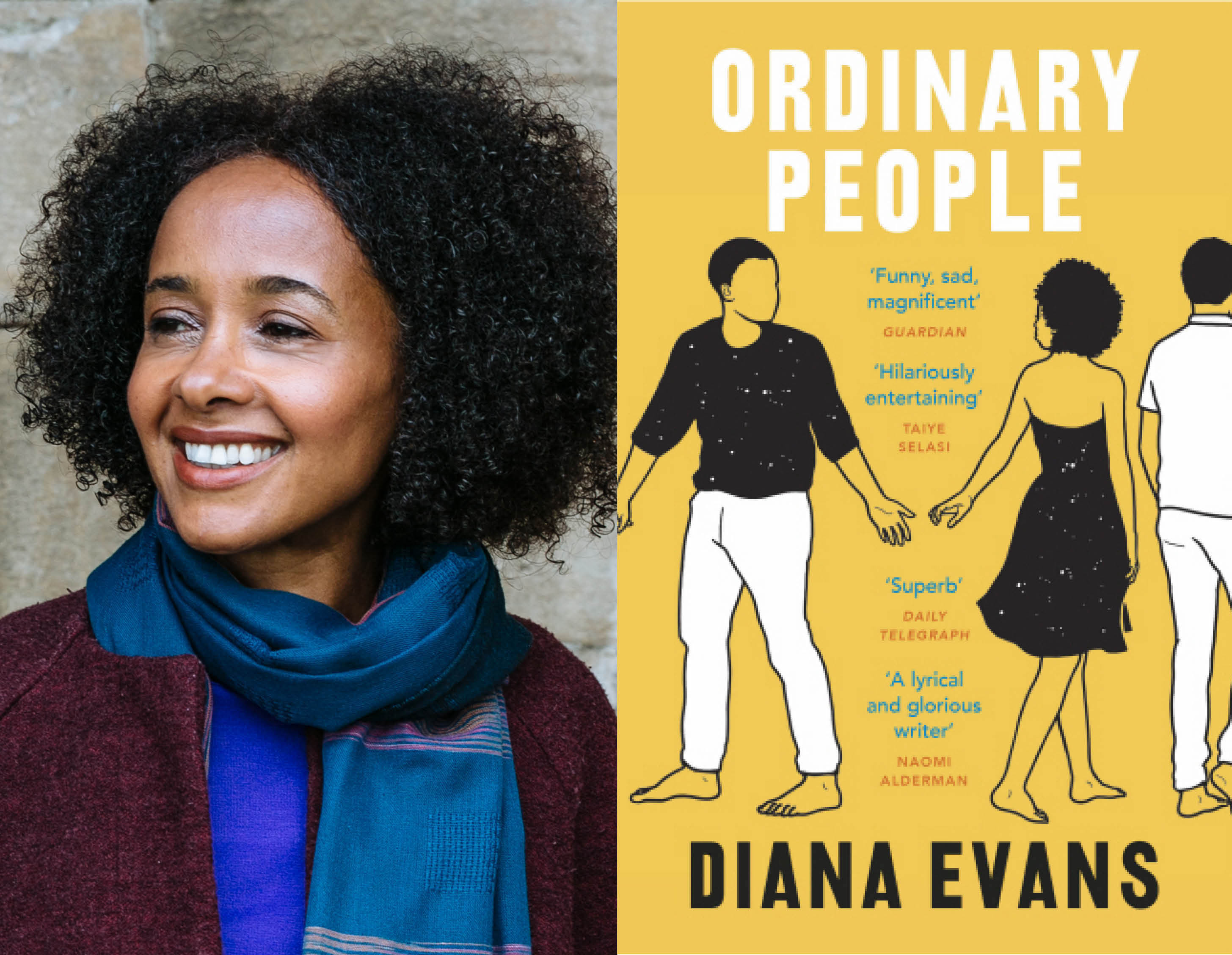

Diana Evans

Toni Morrison once said of her reasoning behind the writing of her first novel, The Bluest Eye, that nobody had ever taken a young Black girl seriously before. This has always stayed with me, this desire to give voice to the dismissed, misunderstood, silenced, marginalised, persecuted and ignored, in this case her unforgettable protagonist Pecola Breedlove, whom I can still remember vividly, as I can so many of Morrison’s characters, scenes and atmospheres even years after reading them.

Her work is an act of giving her community back to itself, so that people – African-Americans but the diaspora as well – can see and witness themselves, and also giving to the world the great beauty and hope that art is capable of. She was a writer whom I remain in awe of yet also feel intimately guided and encouraged by, that profound joint commitment to the folk and the craft, regardless.

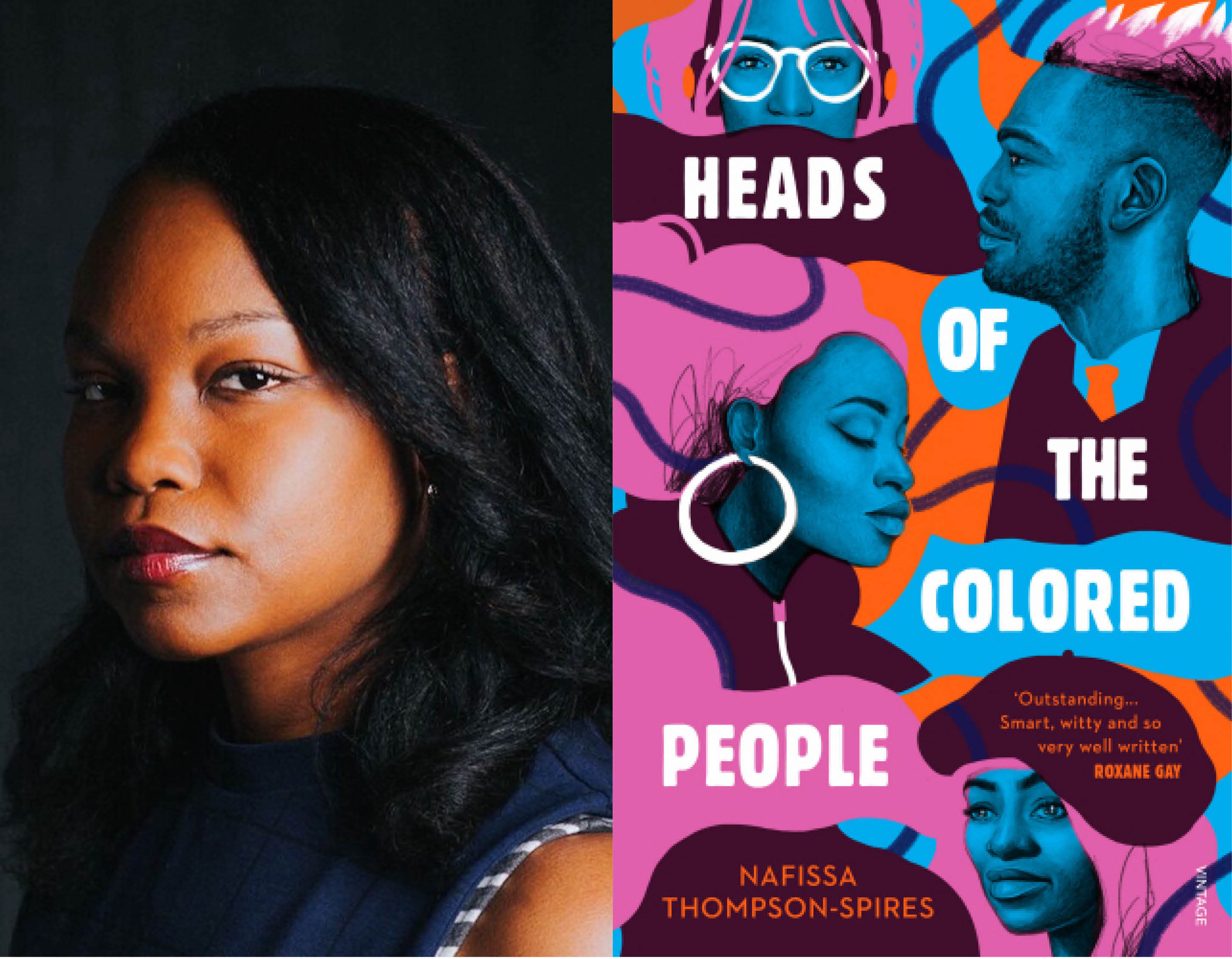

Nafissa Thompson-Spires

I can’t think of a writer as prolific and profound as Toni Morrison, giver of gifts such as The Bluest Eye, Beloved and Song of Solomon, and whose lines I have committed to memory: "Quiet as it’s kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941. We thought, at the time, that it was because Pecola was having her father’s baby that marigolds did not grow" (The Bluest Eye).

Morrison’s haunting characters are steeped in history and its (re)telling through innovative play with form, structure, prose and ‘rememory’. She was arguably one of our best postmodernist writers and yet something altogether different and more nuanced. She wrote the kind of novels that I like best – the kind that, with layers and layers of depth, ask for frequent revisiting. Beyond her longform prose (and plays and children’s books and libretti), Morrison’s essays and critical works have been foundational to my understanding of black womanhood. Playing in the Dark is required reading. Her entire catalogue is, in fact. I can only pray for a sliver of her enduring legacy.

Candice Carty-Williams

There is no writer, living or dead, who has had as much of a hold on me as Toni Morrison. She has basically sat me down at my desk (which was a bed), opened my laptop and clicked on Microsoft Word. There are two quotes of hers that I draw on when I’m asked why I write. The first was especially prominent when I was turning the idea of writing my debut novel Queenie over in my head: "If there's a book that you want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it." Because of Toni Morrison, I felt empowered to write the novel that would have guided me through my early twenties. The second quote is just as important as the first, if not more. It sums up why so many of us tell stories: so that we can say what it is we might not be able to say out loud: "I get angry about things, then go on and work".'

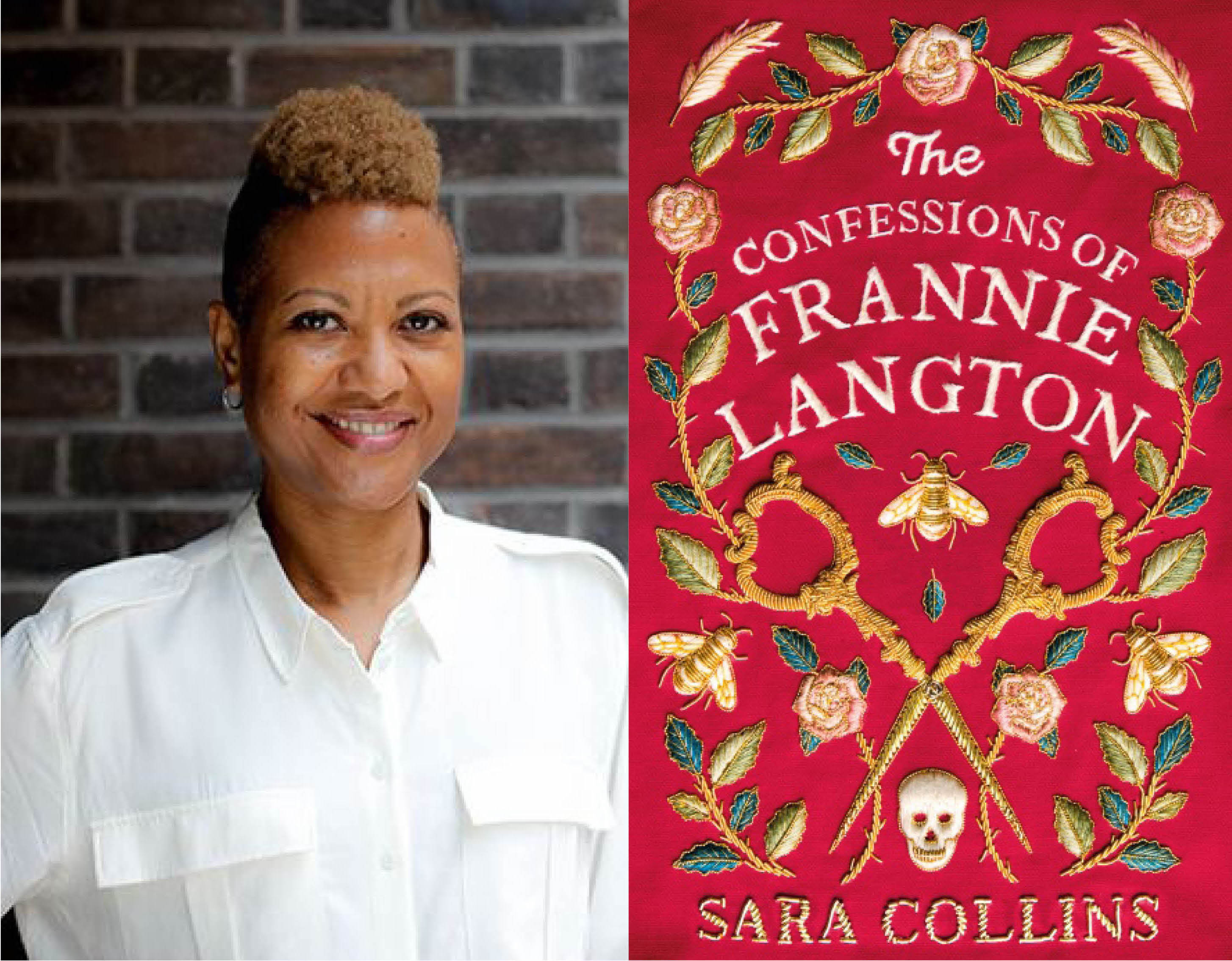

Sara Collins

I was a teenager when Beloved stopped me in my tracks, sent me searching for every book Toni Morrison ever wrote. Almost every line came as an electric shock. Left me forever enraged, enlightened. Enthralled. Before then, all the usual books by long-dead authors crowded my private canon, planted there by the approved syllabus, yet no teacher had ever stood in front of one of my classes and held up a book written by a black author for us to admire.

There would simply have been no route to finishing my own novel without the map that Morrison drew. More than any other writer, she exemplified the power of storytelling as an assertion of humanity. Unapologetically, poetically. What a shame the gatekeepers had to be shown that writing like that could be canonical, but what joy that she’s here to show them. Primus inter pares. First among equals. The best of the best.

Namwali Serpell

When people ask me what I do, I quote Toni Morrison: "I read books. I teach books. I write books. I think about books. It’s one job." I’ve read and taught, written and thought about Morrison’s books for most of my life. In 2020, I’m teaching a course at Berkeley devoted entirely to her brilliance. I’ve analysed and tried to enact the philosophy I see in her novels: a mode of adjacency whereby people and stories and forms sit beside each other, hold hands.

But beyond that, Morrison holds me. Her writing about blackness and womanhood holds my experiences, though I was born far from Lorain, Ohio. Her voice – precise, beautiful, warm, gripping – holds me, sometimes too close, but in a way that thrills rather than threatens. And she holds me to account. She is an absolute model of integrity: uncompromising, fearless, full to the brim with everything she is.

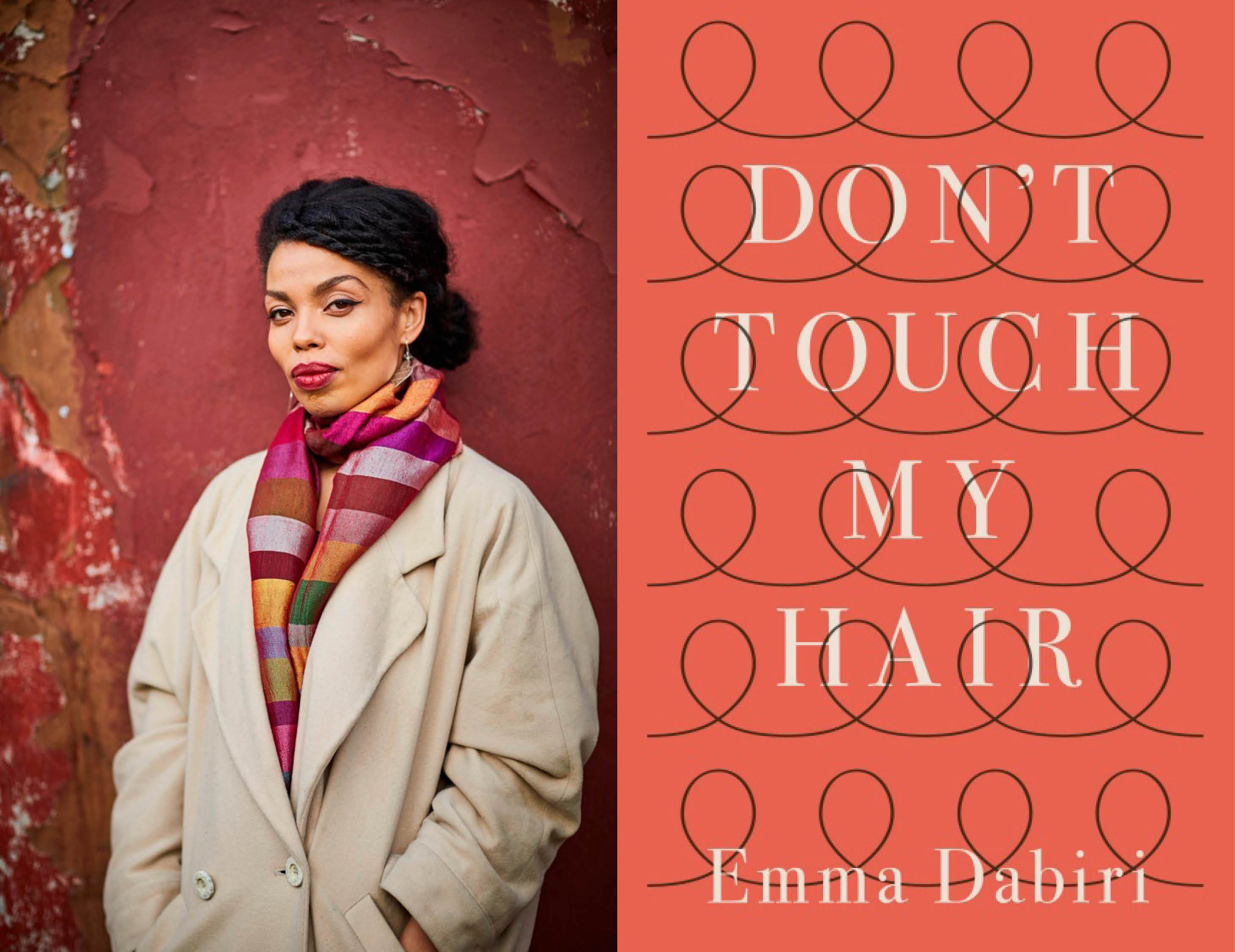

Emma Dabiri

There exists for me a handful of writers and thinkers who have sketched an outline, distinct enough for me to discern the trace of a path, hidden– yet not entirely obscured – the presence of which reassures me when I feel most isolated as a result of my ideas. Toni Morrison is one of these.

While I would never dream of comparing my writing to hers, what she achieved provides the co-ordinates from which I can map my own location. The American worlds she conjures reverberate with the echoes of the West African spirit traditions of our shared ancestors, rendering the magical tantalisingly tangible. Reading Morrison you are intimately drawn into the communities she creates. Through her writing I have travelled through space and time, from rural all-Black backwaters to Jazz-era Harlem. I have been a visitor in communities populated by characters of complex personhood who also happened to be Black.

And while the facts of Blackness were always central to the subject matter, the race of the characters would never itself provide the rationale for Morrison’s writing. Reading interviews with Morrison, I’ve heard her speak about this avoidance of cliché and lazy generalisation: ‘As soon as I say “Black woman”, I can rest on or provoke predictable responses, but if I leave it out, I have to talk about her in a complicated way.’ And yes, Morrison’s work can be complicated and it is challenging, but by God is it worth the effort. I can’t overemphasise my gratitude for all that she gifted us.

This article was originally published in February 2019.