- Home |

- Search Results |

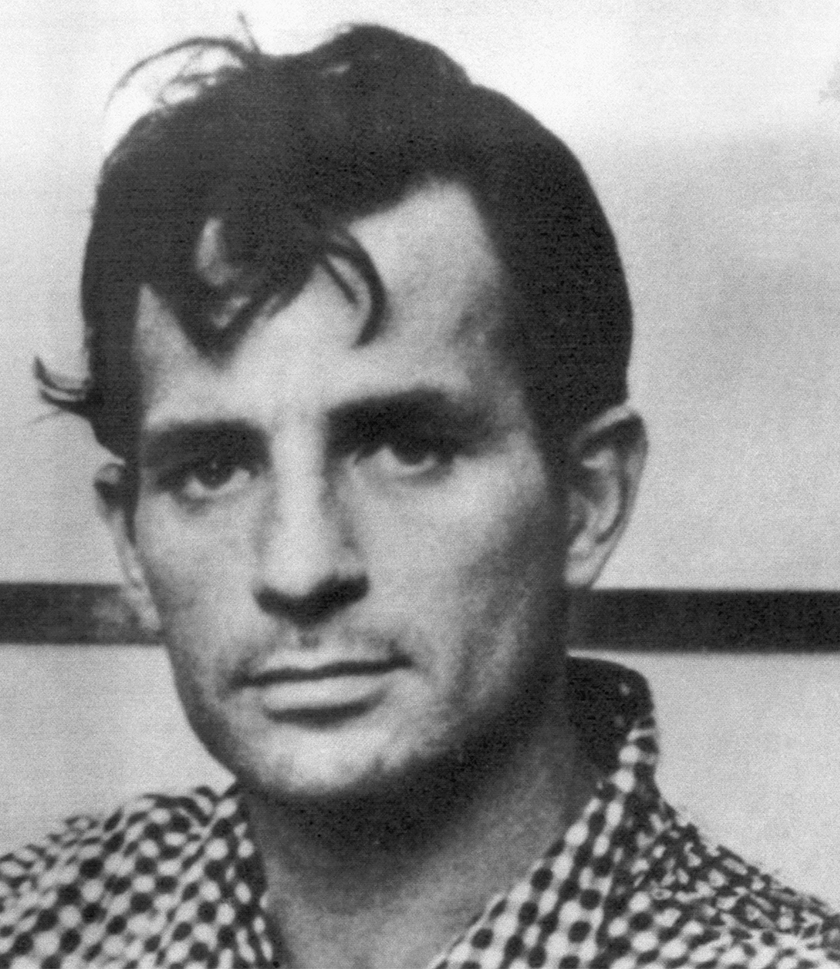

- Jack Kerouac’s wild, futile quest to find his French ancestry – and the duo who did

I’ll use my real name here, Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac, because this story is about my search for this name in France

– Jack Kerouac, Satori in Paris (1966)

When Jack Kerouac set off to France at the height of his literary fame, his goal was neither book tour nor leisure trip. After decades of wandering, and at the age of 43, the American author longed for his roots. Landing in Paris on 1 June, 1965 and travelling to Brittany, Kerouac, who recounted his expedition in Satori in Paris (1966), was determined to find traces of his ancestor, a 17th-century Breton who emigrated to Canada. Generations of Kerouacs had cherished the myth of their forebear: a dispossessed aristocrat named de Kervoach.

Kerouac read French archives and looked for namesakes, but despite his 'Satori' title (“Japanese for ‘sudden illumination’”), he only found dead ends. His ailing health thwarted plans for more trips to Brittany, and he died four years after that first trip, on 21 October, 1969.

The mystery would, instead, take another 30 years to unravel. In 1999, historian Patricia Dagier and journalist Hervé Quéméner published a book retracing intricate genealogical studies that finally solved his quest.

His father cultivated the family’s Brittany lore, repeating: “Ti-Jean, don’t forget that you are Breton!”

While Kerouac may have claimed to have been “the first Lebris de Kérouack ever to go back to France in 210 years”, he wasn’t. In fact, the Kervoacs, Kirouacs and Kerouacs (all derived from Kervoach) of North America had been searching for centuries – some had even boarded steamboats to Brittany – but all pursuits had failed.

In 1978, descendants created the Kirouac Family Association to “discover more about [their] Breton origins”. They based their research on the 1732 marriage certificate of “Maurice-Louis-Alexandre Le Bris de Kervoach, trader, son of sieur Le Bris de Kervoach and of dame Véronique-Magdeleine de Meuseuillac, from Beriel, of the Cornwall diocese, Brittany”, to Louise Bernier in Nouvelle-France (now Québec). They knew he had three children, died on 5 March 1736, and that his widow, inheriting numerous debts, tried her whole life to contact her aristocrat Breton relatives – with no success.

By the time Kerouac was born in 1922 – as Jean-Louis – his family had dwelled on their noble Kervoach ancestor for two centuries, Hervé Quéméner, 74, told me. The son of Canadian immigrants settled in Lowell, Massachusetts, Jean-Louis Kerouac’s native language was French; he would only learn English, and become ‘Jack’, at school. His father cultivated the family’s Brittany lore, repeating time and again: “Ti-Jean, don’t forget that you are Breton!”

'As he felt death approaching, he grew monomaniac about his origins'

Kerouac’s years on the road bore little reference to Brittany, but by 1965, the writer’s severe alcohol and drug use was taking its toll. As Quéméner explained: “As he felt death approaching, he grew monomaniac about his origins. Twice an émigré who had roamed all his life, [Kerouac] made Brittany his anchor.”

Clues of Kerouac’s Brittany obsession abound in his literary production. He had yet to be crowned ‘King of the Beats’ when he signed his French collection of poetry La vie est d’hommage (1940) as “Prince of Brittany”. In Big Sur (1962), the story of his summer in a West Coast hut, his alter-ego Jack Duluoz – another Breton name – roars to the Pacific Ocean: “I am a Breton!” Big Sur’s 'SEA' poem is peppered with Breton sounds (“Ker plotsch”, “Kerarc’h”) conveying the backwash of sea and rocks. Kerouac writes: “Fish in the sea / Speak in Breton / My name is Lebris / De Keroack.” Quéméner said he hopes academics will one day analyse Kerouac’s works “in light of his Breton obsession”.

There isn’t a page of Satori in Paris on which Kerouac fails to mention that his “folks came from France, and the name was de Kerouac.” But his ancestor was nowhere to be found, which aggrieved Jack: “Besides it’s all too long ago”, he wrote, “and worthless unless you can find the actual family monuments in fields, like with me I go claim the bloody dolmens of Carnac?” The novella reads like dazed travel entries: Kerouac smoking inside the French national library; wandering in Paris before setting off to Brest, a naval port city at Brittany’s western tip Finistère (“where the land ends”). There, he shared cognac and stories with a bookseller named Le Bris, supposedly a remote cousin – another red herring.

Back in New York, Kerouac befriended Breton author Youenn Gwernig, from Huelgoat, Finistère, who discussed Brittany with Jack on their bar crawls. In 1967, Kerouac wrote to Gwernig: “I have to see Brittany with you (...) We’ll see what we find about les pirates Lebris de Kerouac this time!” The friends planned to travel to Huelgoat, but Jack’s untimely death cut them short.

Why would an affluent young man emigrate to Canada, she wondered.

With Gwernig, Kerouac never knew he almost touched the truth. In 1996, Clément Kirouac, a Canadian member of the Kirouac Family Association, sent a call to French genealogists for information on 'Le Bris de Kerouac'. It intrigued historian Patricia Dagier: since there was no trace of the name, she concluded that “the ancestor’s identity and that of his parents were false” and focused on his place of birth instead.

In doing so, she discovered that 'Beriel', as the Canadian priest had spelled it in 1732, was really 'Berrien', a Huelgoat parish. There was no Le Bris de Kerouac but a Le Bihan de Kerouac family. Among them, Urbain-François Le Bihan de Kervoac, the son of a notary, vanished from the archives around 1720 without being listed as dead.

Why would an affluent young man emigrate to Canada, she wondered. The local court’s archives held the answer: accusations of theft and frivolity had brought scandal on Urbain-François. Dishonoured, he had sailed away and built a new life trading fur in Québec. He appeared in Canadian records under various names and in 1732 was forced to marry the young woman who had carried his child. To protect his inheritance in Brittany, Dagier explained, he had given a false name, 'Le Bris' for 'Le Bihan', and claimed nobility, which at the time provided legal protection. Urbain-François probably hoped to return home, but died in Canada four years later.

Urbain-François, like his famous offspring, was really a creative vagabond with a taste for embellishment

His intricate signature, the same in Huelgoat and Québec, was the key. Finally, Dagier could declare: “The ancestor of the American Kerouacs was no other than this son of a notary, the talk of the town in 1720 Huelgoat: Urbain-François Le Bihan de Kervoac.”

No blue blood ran in his veins: Urbain-François, like his famous offspring, was really a creative vagabond with a taste for embellishment. Quéméner, who wrote the book with Dagier, fondly recalls this “treasure hunt". “We tailed him in the archives”, he said. “You can change your name, but you won’t change your signature.”

Urbain-François’ strategy worked marvels, Dagier noted: “His descendants were doomed to look for him ad nauseum.” Over the years, accents and illiteracy led to a myriad of Kerouac spellings while 'Le Bris' disappeared. Although “pure fantasy”, the nobility myth lived on, spurring Kerouac’s dreams of being descended from Breton princes.

Dagier and Quéméner’s book, republished in 2019 for the 50th anniversary of Kerouac’s death, interlaces his storyline with that of Urbain-François to better highlight the “convergence of destinies” between two deceivers who dreamed, roamed and evaded posterity. Kerouac never paid his daughter’s alimony, nor acknowledged the Beat’s influence on the hippie movement.

He may, though, have drawn pride from the tributes Brittany has paid him since 1999. In Huelgoat, a plaque now celebrates Urbain-François and in Carhaix, Finistère, artists take to the 'Kerouac stage' of the annual local music festival. Jack’s own legend has grown roots.