- Home |

- Search Results |

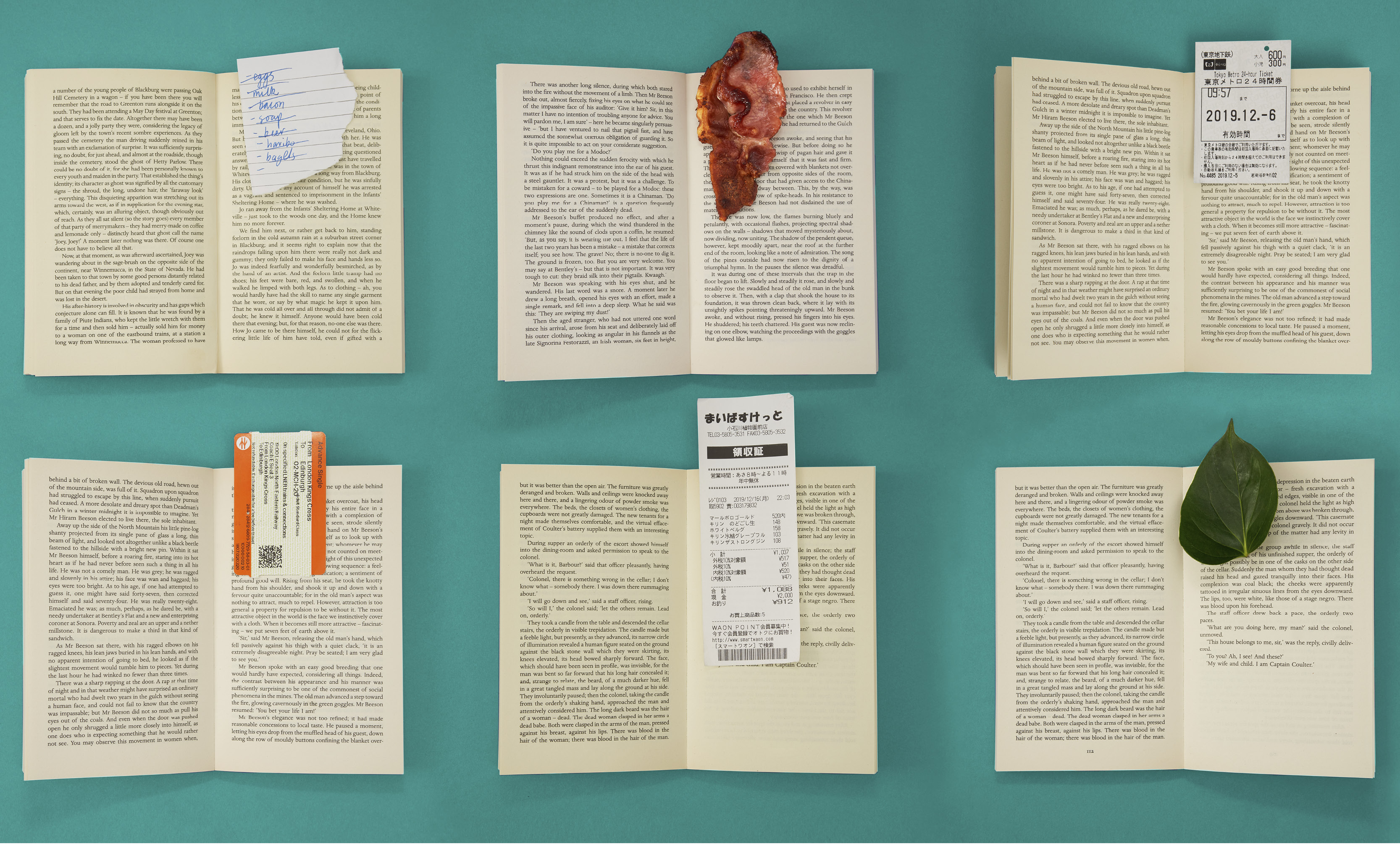

- How your choice of bookmark can tell its own strange story

I picked up my copy of Three Men in a Boat for the first time in years recently, only to find I’d marked my page with a train ticket from Chesterfield to Newcastle, a return stub from a visit to someone I was seeing at the time.

Suddenly I had a flashback to sitting on the journey home, watching the sun set and wishing I was going in the opposite direction. I was full of that glowing feeling you get when you’ve been hanging out with someone you really, really fancy. All that comingled with the chatty warmth of Jerome K. Jerome's account of a journey his own; a boating holiday from Kingston to Oxford in 1889.

It was a weird sensation, being yanked into the past like that. And it made me wonder whether what we use to mark our place in books offers any sort of insight into the psyche. You probably fall into one of three camps: those who buy proper bookmarks made of sturdy leather and tassels; people like me who grab the nearest thing that looks thin enough to fit in a book; and sadists who gleefully mutilate their books by folding page corners.

Thomas Hardy used bits of paper with scribbled reminders to look things up

Writers have given away a little of themselves in their choices, too. Mary Shelley used an envelope of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ashes as a bookmark in her copy of Adonais, an elegy written by Shelley for John Keats. One (slightly dubious) legend says Charles Dickens bought a bookmark made from the skin of hanged serial killer William Burke. Others have been less rational. According to Clive James, literary critic Cyril Connolly plumped for a raw rasher of bacon.

My approach – of using whatever is at hand – nods at a scrappy, ad-hoc approach to reading, grabbing a few minutes here and there when I remember. I’m in good company, though: Thomas Hardy used bits of paper with scribbled reminders to look things up – one surviving fragment tells him to dig into an anthology of Ancient Greek literature.

After finding that train ticket I started rummaging through old books, and found all sorts. A little handwritten note from my dad was in a copy of Bob Stanley’s Yeah Yeah Yeah, his loopy, dashing scrawl telling me to “Enjoy!” whatever it was he’d sent in the post. Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature used a ticket from a forgotten Horrors gig. A water bill from six years ago, found in an MR James collection, suddenly rekindled a long-dormant feud with a flatmate I’d not thought about since moving out.

A water bill from six years ago rekindled a feud I'd forgotten about

When those little pieces of flotsam drift back to the surface, they drag all sorts of things up with them. Some piece of ephemera that wasn’t meant to make it this far can become accidentally meaningful. Your experience of a book is tethered to the time and place you read it in. Finding these little artefacts can transports us back to the people we were when we first encountered a story and a writer, how intensely we felt while reading it for the first time. It’s not just nostalgia, it’s a way of channelling the thoughts and experiences that resonated then from the perspective of what you know now.

So check your own shelf. A sorry-we-missed-you slip, a business card from a B&B, a loyalty stamp card from that barber you’ll never go back to: they’re all opportunities for time-travel.