- Home |

- Search Results |

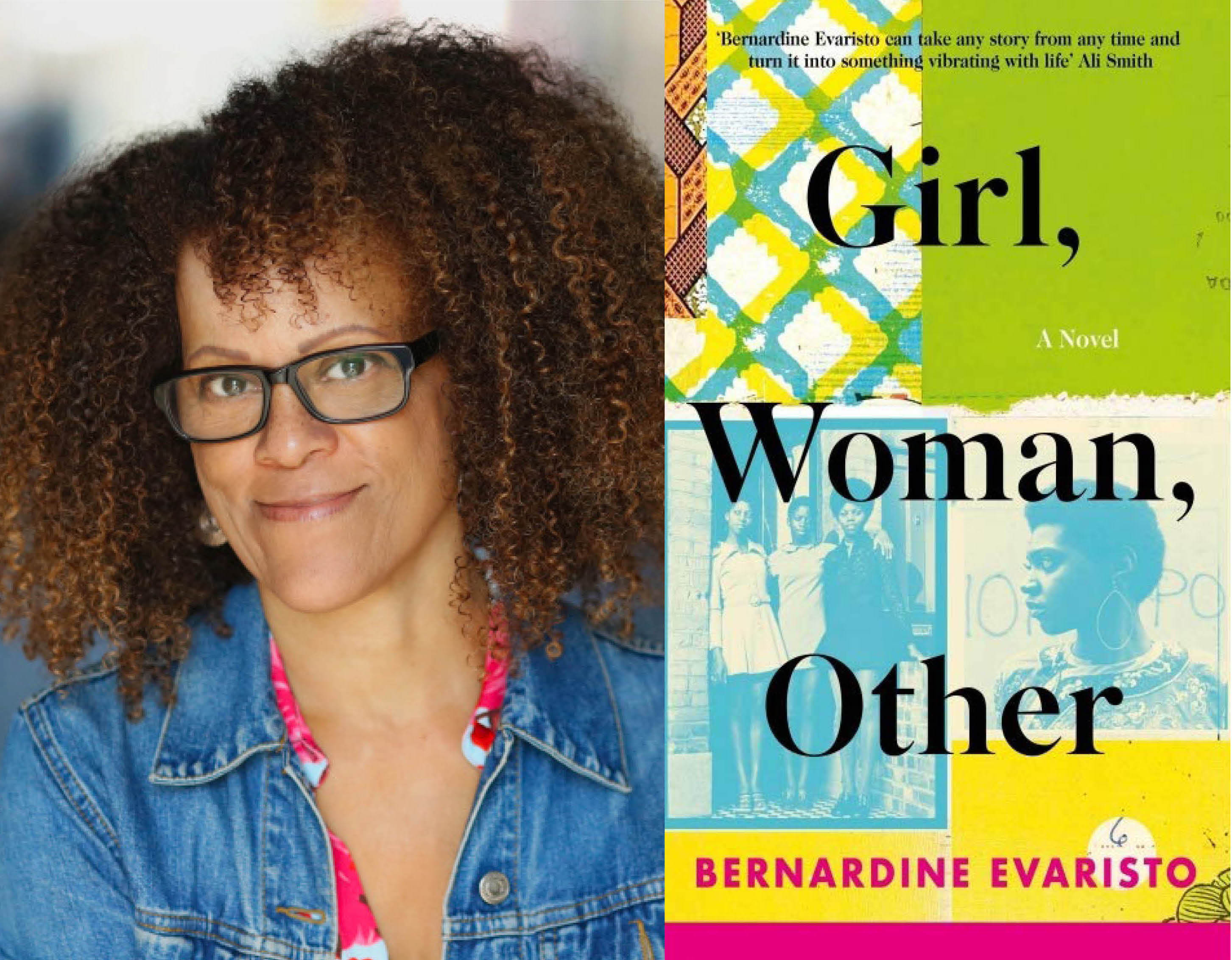

- Bernardine Evaristo: ‘Older black women, who writes about that?’

Bernardine Evaristo: ‘Older black women, who writes about that?’

Five Dials interviews novelist Bernardine Evaristo to find out about her latest book Girl, Woman, Other – a love song about modern Britain and a black womanhood.

Bernardine Evaristo is the award-winning author of eight books of fiction and verse fiction. Her other writing includes short fiction, drama, poetry, essays, literary criticism, and projects for stage and radio. She is currently Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University London and Vice-Chair of the Royal Society of Literature, and her new novel Girl, Woman, Other is published by Hamish Hamilton.

Girl, Woman, Other follows the lives and struggles of twelve very different characters. Mostly women, black and British, they tell the stories of their families, friends and lovers, across the country and through the years.

Joyfully polyphonic and vibrantly contemporary, this is a gloriously new kind of history, a novel of our times: celebratory, ever-dynamic and utterly irresistible.

Five Dials: Where did the idea for Girl, Woman, Other come from?

Bernardine Evaristo: I suppose each book I write speaks to the one that came before. So the book I wrote before was Mr Loverman, which was about a 74 year-old gay Caribbean man living in London, and there were some secondary figures in his wife – a woman in her 60s who didn’t know he was gay, his two middle aged daughters, his grandson and his lover Morris.

By the time the book was finished I was really interested in the three woman’s stories, in particular the two daughters. One of the things I realized is that I try to write the stories that aren’t out there. A lot of us writers of colour will say that we want to write those books that we feel should be out there.

When I was writing Mr Loverman I kept thinking ‘Who writes about 70-something year-old older black men in this country?’, and I couldn’t think of anyone, let alone writing a gay character. Then when I was writing the wife I was thinking, ‘Older black women, who writes about that?’ I’m not sure, but I don’t think anybody does. And then middle-aged women in their 40s and early 50s. That’s also unusual. By the end of writing Mr Loverman, I realized there are so many stories of the different black generations in this country we don’t hear about.

Younger writers often don’t reach my age and carry on publishing. Younger writers often write from a younger perspective. If they write from an older perspective, that person is usually mad in some way – they have dementia or something. Younger writers can’t conceive of that person having a happy, healthy life.

So because there aren’t many of us writing from a black British female perspective there is a real paucity of characters of all generations, but especially middle-aged and older generations.

A lot of black British female writers have come and gone since I’ve been around. I’m becoming a veteran. I’ve always given myself a lot of freedom to write from any perspective. I go with the characters that go with me. That may be a male protagonist, but with this one I really felt I wanted to write the women’s stories. How many female characters can I write that are all protagonists in a single story, and make it work?

Going back to the origins of this novel, it was actually a commission in 2014 by BBC Radio. They commissioned me to write a story for the anniversary of Dylan Thomas’ birth. I wrote a short story with four female black characters in the form that novel is now. I call it ‘fusion fiction’, a slightly experimental form. When I wrote those four characters I knew I would use it for the basis of my next book.

At one point I thought maybe I could have one hundred protagonists. Toni Morrison has a quote: ‘Try to think the unthinkable’. That’s unthinkable. One hundred black women characters? How can I do that? I need a more poetic form. Now there are only twelve main characters.

5D: There are so many different voices in this novel. Where did the voices come from? Are there some that resonate more with you?

BE: In the 80s I did run a theatre company. I was a dyke. So Amma has a little bit of my history. But I’m not her. I did not sleep with three hundred people. That’s all exaggerated. And then Yazz is one of my goddaughters who’s very bright and very feisty. Dominique is a composite of women I knew years ago. As somebody who used to write for theatre and used to act, I love getting inside my characters and creating them. Even though this book isn’t in the first person, it feels like it’s in the first person because the reader is inside their heads. It’s a bit like Carmel in Mr Loverman, except Carmel is written in second person. This is in close third. It’s like they’re talking to you. That process, I love it.

I also had to have a non-binary character, because that’s such a big part of the conversation at the moment. I’ve got twelve characters, different sexualities; I needed someone whose gender is changed in some way. Writing their character with ‘they’ was a challenge because I thought, how do I do that and not bring attention to the ‘they’ all the time?

5D: Why did fusion fiction feel the most appropriate way to tell this story? And why was it in novel form?

BE: With Mr Loverman, there are no standard full stops throughout the text, but each chapter ends with a full stop. So with Girl, Woman, Other there’s a full stop at the end of each section. There was something about the flowing way in which I was able to write the story that meant I could go all over the place. It’s almost like prose poetry. There aren’t any paragraphs. As you’re reading it, the sentences flow into each other.

The fluid way in which I shaped, lineated and punctuated the prose on the page enabled me to oscillate between the past and the present inside their heads, outside their heads, and eventually from one character’s story into another character’s story.

5D: I’m interested in how that then becomes a novel. Why not a long-form poem or a play? It could read as all of those things.

BE: It’s a prose poem, if anything. Fusion fiction for me puts the emphasis on the fiction. It was quite fluid to write. I really enjoyed that process. But it was really hard when I came to edit. The freedom I gave myself in terms of form meant that I couldn’t quite see what was wrong with it in the way that you can with real punctuation and lineation. Fusion fiction as a form might be easier for poets, because managing the revision of it in 120,000 words is very challenging.

5D: Your characters are all connected across a vast span of history. Can you tell me more about your interest in ancestry?

BE: I’m obsessed. I’m not even Nigerian, you know. I found out on www.ancestry.com. I got myself tested and they told me I’m from Togo and Benin. But it’s all the same. Those counties were fake constructs. Apparently I’m a fake Nigerian.

5D: How did ancestry feed into the story? Why was it an important way to link the characters? There is a recurring theme of mother-daughter relationships in the novel, for instance.

BE: It was just an inter-generational thing. I wanted it to span every generation. Even though I don’t have a protagonist who’s a young teenager, a lot of the characters went through that stage. So you have a sense of who they were as children, how they became adults, and then how they are as mothers. I’m deeply interested in how we become the people we are. Coming from a radical feminist alternative community in my 20s, and then seeing these people in their 40s and 50s, I’ve seen people become extremely, almost, conservative, establishment, having lost all the free-spiritedness, oppositionality and rebelliousness of their younger years. To me that’s fascinating. When I meet young people today and they are a certain way, I think: ‘You don’t know who you’re going to be.’ That feeds into the fiction. How do we parent our children? What are our ambitions for our children? How does that link to how we were raised? How does gender play out?

With ancestry, I wanted some span of Africa, from East Africa to West Africa and the Caribbean. That’s who we are in this country. Our roots are all over the place.