- Home |

- Search Results |

- Houses of death: the horror of life in a Victorian hospital

Houses of death: the horror of life in a Victorian hospital

Riddled with dirt, disease, gristle and gore, the operating theatre back then was far removed from what we associate with hospitals of today. Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris, a medical historian, takes us through daily life in a Victorian hospital.

In 1825, visitors to St. George’s Hospital in London discovered mushrooms and maggots thriving in the damp, dirty sheets of a patient recovering from a compound fracture. The afflicted man—believing this to be the norm—had not complained about the conditions, nor had any of his fellow bedmates thought the squalor especially noteworthy. Those unlucky enough to be admitted to this and other hospitals of the era were inured to the horrors that resided within.

Today, we think of the hospital as an exemplar of sanitation. However, late Georgian and early Victorian hospitals were anything but hygienic. A hospital’s ‘Chief Bug-Catcher’—whose job it was to rid the mattresses of lice—was paid more than its surgeons at this time.

Hospitals were breeding grounds for infection and provided only the most primitive facilities for the sick and dying, many of whom were housed on wards with little ventilation or access to clean water. As a result of this squalor, these places became known as ‘Houses of Death’.

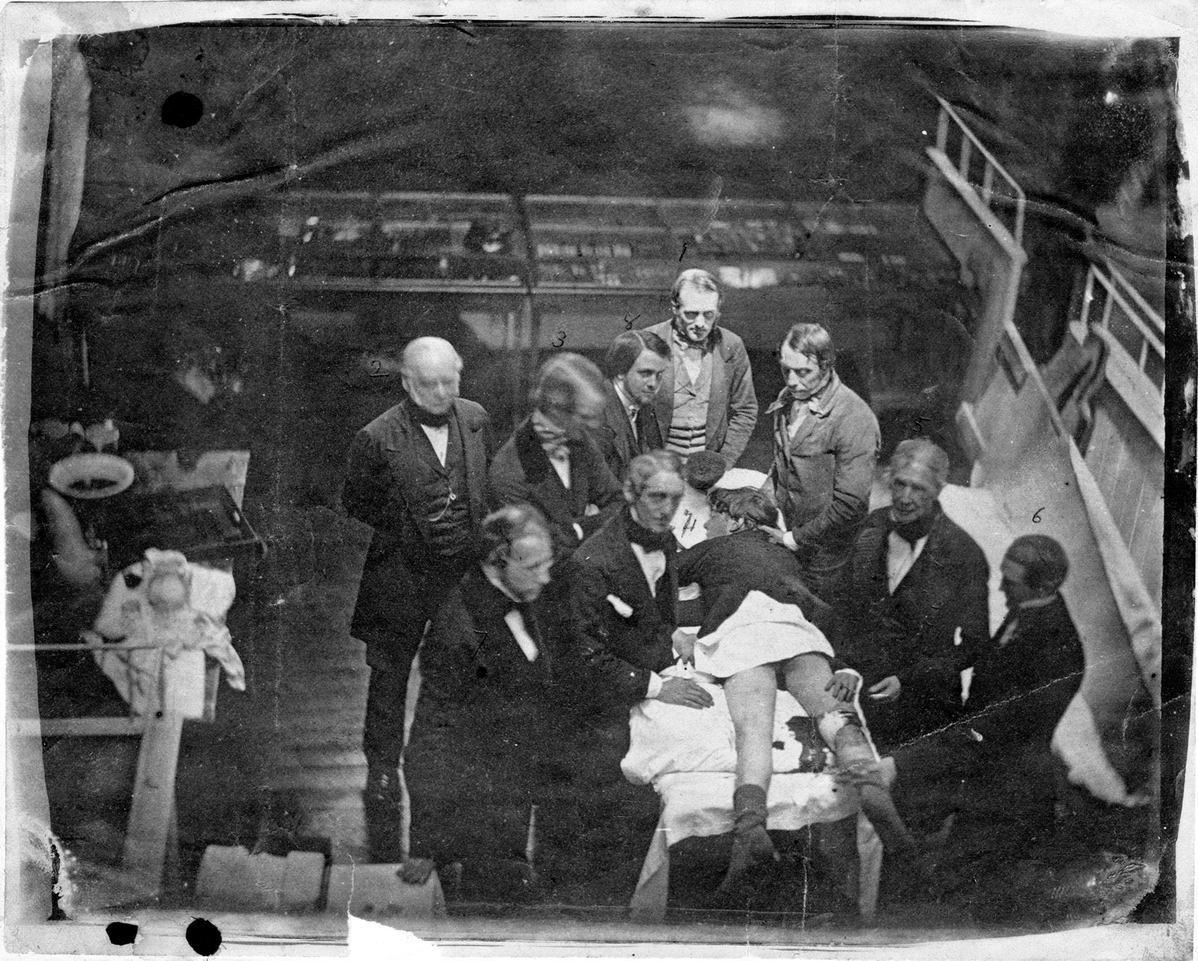

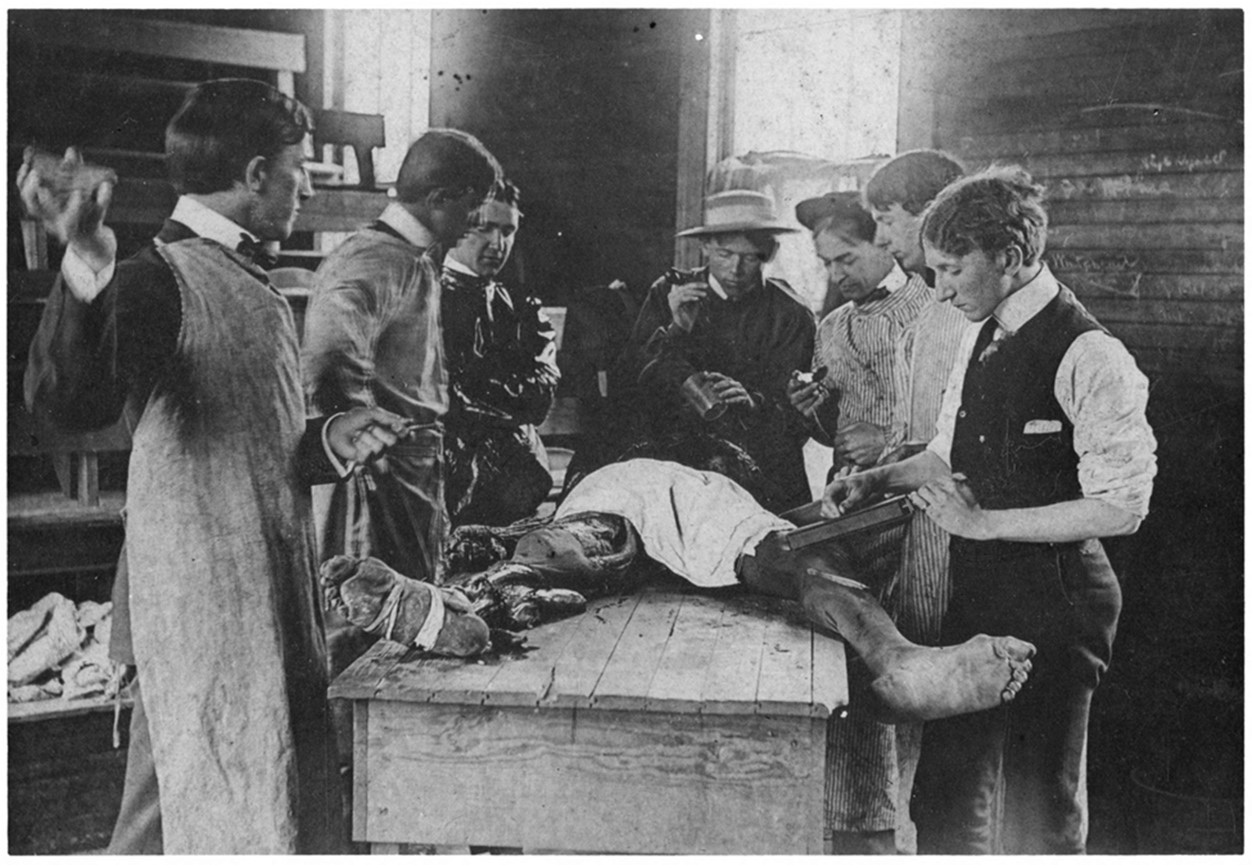

The operating theatre itself was just as dirty as the surgeons working in them. It was frequently filled to the rafters with medical students and curious spectators, many of whom had dragged in with them the dirt and grime of everyday life. The surgeon John Flint South remarked that the rush and scuffle to get a place in an operating theatre was not unlike that for a seat in the pit or gallery of a playhouse. People were packed like herrings in a basket, with those in the back rows constantly jostling for a better view, shouting out ‘Heads, Heads’ whenever their line of sight was blocked.

Most operating theatres looked more or less the same in this era. They consisted of a stage partially enclosed by semicircular stands rising one above another toward a large skylight that illuminated the area below. On days when swollen clouds blotted out the sun, thick candles lit the scene. In the middle of the room was a wooden table stained with the telltale signs of past butcheries. Not all patients were laid flat. Before the dawn of anaesthetics in the 1840s, many were sat upright in an elevated chair. This prevented them from bracing when the surgeon’s knife began to dig into their flesh. Unsurprisingly, they were also restrained, sometimes with leather straps. Underneath their feet, the floor was strewn with sawdust to soak up the blood. On most days, the screams of those struggling under the knife mingled discordantly with everyday noises drifting in from the street below: children laughing, people chatting, carriages rumbling by.

Before germs and antisepsis were fully understood, remedies for hospital squalor were hard to come by. The obstetrician James Y. Simpson suggested an almost-fatalistic approach to the problem. If cross-contamination could not be controlled, he argued, then hospitals should be periodically destroyed and built anew. Another surgeon named John Eric Erichsen voiced a similar view. ‘Once a hospital has become incurably pyemia-stricken, it is impossible to disinfect it by any known hygienic means, as it would to disinfect an old cheese of the maggots which have been generated in it’, he wrote. There was only one solution: the wholesale ‘demolition of the infected fabric’.

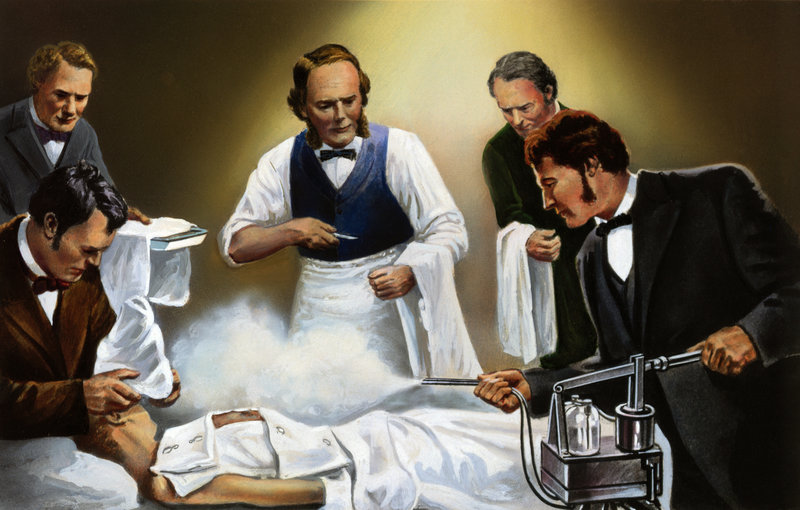

By the 1860s, the situation had reached critical mass. At a time when surgery couldn't have been more dangerous, an unlikely figure stepped forward: Joseph Lister, a young, melancholy Quaker surgeon. By making the audacious claim that germs were the source of all infection—and could be treated with antiseptics—he changed the history of medicine forever. Towards the end of the 19th century, hospitals ceased to be houses of death and instead had become houses of healing.