- Home |

- Search Results |

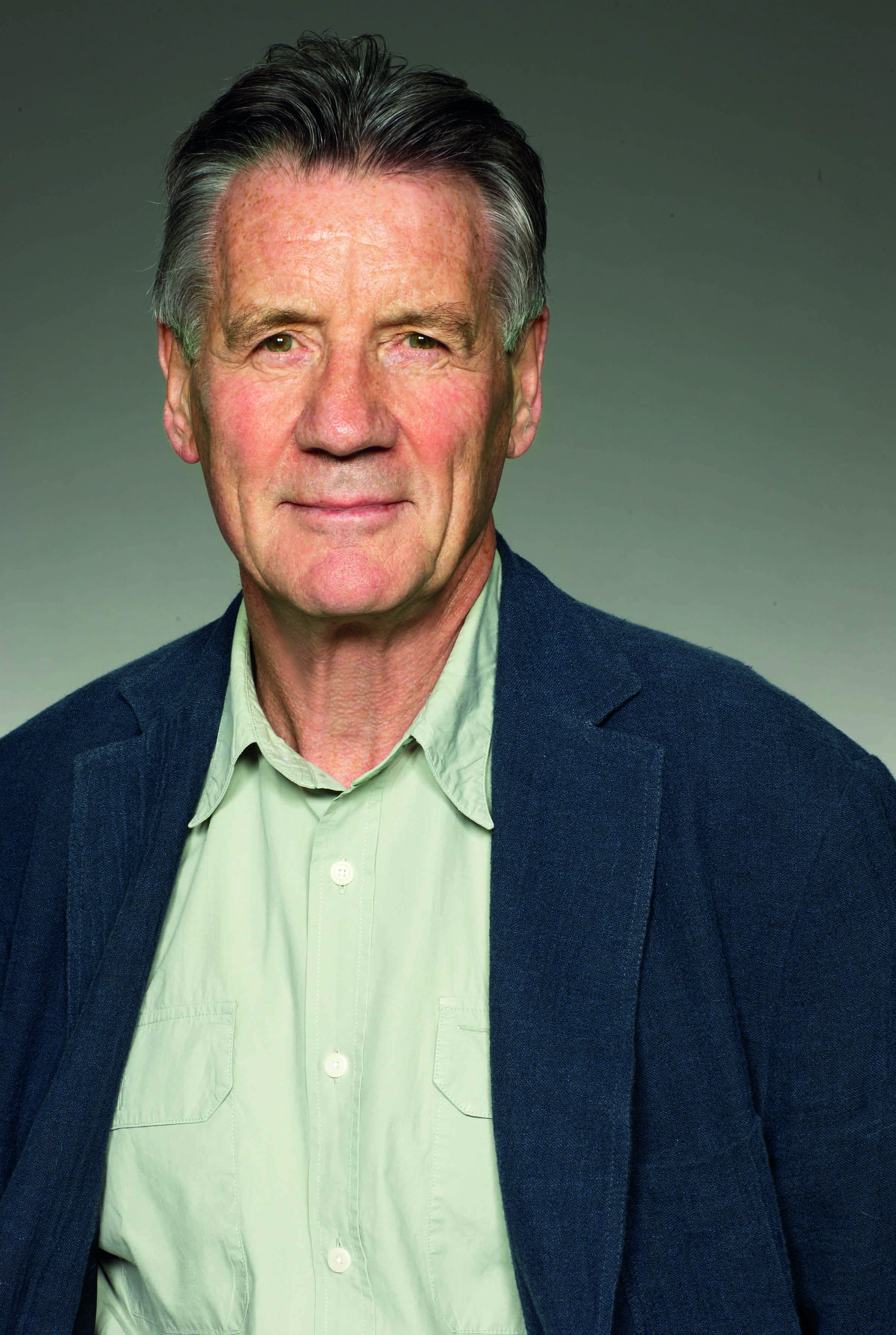

- Michael Palin on HMS Erebus: ‘a story of life, death and resurrection’

Michael Palin on HMS Erebus: ‘a story of life, death and resurrection’

In 1848, HMS Erebus disappeared in the Arctic, its fate a mystery. In 2014, it was found. Michael Palin brings the remarkable ship back to life, following its epic voyages of discovery to ultimate catastrophe. He talks to Anna James.

“I do think some people will say, Michael Palin’s written a book about a ship in the middle of the nineteenth century? Why?! What’s happened to him, does he not do comedy anymore? – but I just sniffed out a good story.”

The ship in question is the HMS Erebus, built in Wales in 1826. Palin’s new book follows its birth, life and death over two epic journeys - to the far south, and then the far north.

The Erebus’ first journey was a resounding success, bringing back huge amounts of new information about the Antarctic, and making the careers of several of the men on board. Its second journey was an attempt to navigate the Northern Passage, where the ship and its crew were lost: “The two together are tragedy and comedy, the two masks, success and heroic failure”, says Palin.

Palin first encountered the Erebus after being asked to give a talk at the Athenaeum Club about a former member. He chose Joseph Hooker, who became known as a “botanical pirate” after bringing rubber seeds from Brazil to Kew Gardens, where they were germinated and sent across the British colonies, effectively ending Brazil’s rubber trade. During his research, Palin realised that before that, aged 23, Hooker was on one of the first expeditions to the Antarctic, on board a ship named the HMS Erebus. “I was drawn to it for all sorts of reasons. It seemed to me a very good dramatic tale – even the fact that the ship was named after the darkest part of hell, and it did go to the darkest parts of hell, really, in terms of human survival.”

After Palin gave his talk in February 2013, fate seemed to intervene: “In 2014, after the Monty Python farewell shows at the O2, I suddenly had a bit of a gap because a travel programme I was going to do fell through, and then, within three weeks of finishing at the O2, the Prime Minister of Canada announced that they had discovered the wreck of the Erebus. From the moment they discovered the wreck, I thought, ‘there’s a story of life, death and resurrection – I’ve got to tell it.’ This is a book for those with open minds and a sense of curiosity, which is the way I approached it.”

There are still a lot of unanswered questions about the final fate of the ship, but Palin never seriously considered writing the book as anything other than non-fiction.

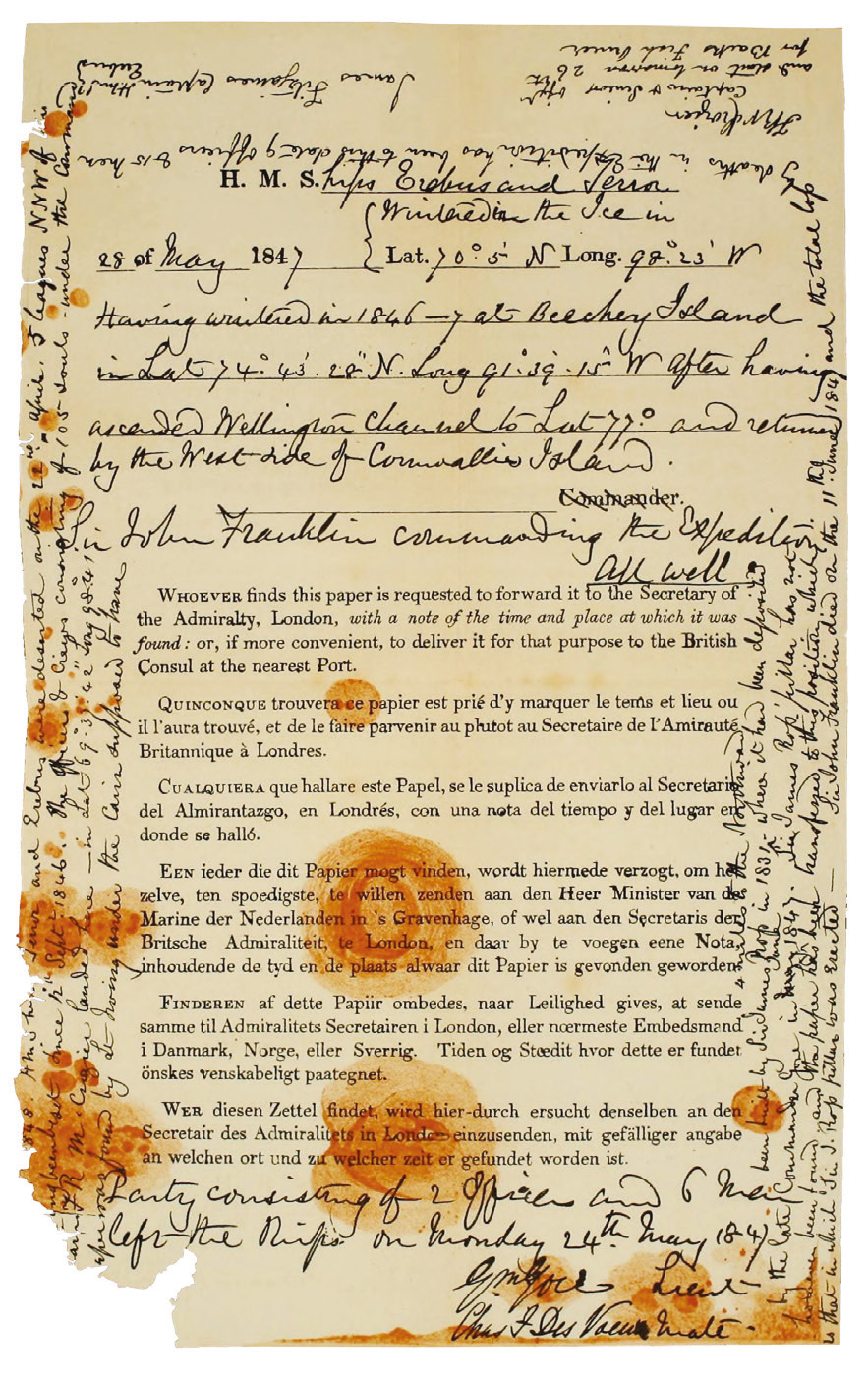

“There’s the temptation to write in a little bit of fantasy, what might have happened, etc. But what attracted me, really, was the truth of the story itself. It’s such an extraordinary story, so getting the facts right was very, very important to me.” It was key for Palin to try and construct as accurate a portrait as possible, through contemporary accounts, ships’ logs, letters from the crew members, as well as secondary sources from historians and specialists. Some of the crew members from the original voyage had published their own accounts - including James Clark Ross, the captain, and Robert McCormick, the assistant-surgeon and naturalist - which formed the foundation of Palin’s reconstruction of the voyage.

The ship was named after the darkest part of hell, and it did go to the darkest parts of hell, really, in terms of human survival...

These voices and personalities are the backbone of Palin’s book, giving the tale character, warmth and a level of human interest that makes Erebus something more than just naval history. Palin brings in as much of their original language as possible – in particular McCormick’s eccentric mix of awe and bloodlust for the natural world. “Today I knocked down an old penguin with my geological hammer,” reads one entry from his diary.

But some of the most human and moving moments come from snippets of letters from the less well-educated crew members, says Palin. “Those little glimpses of how people really felt, the raw stuff, someone telling their wife they might not see them again. I wish I’d had more of those, but it’s very, very hard to find crew documents.” One such letter even reveals that the crew carved a makeshift pub out of the ice, deep in the Antarctic, to celebrate New Year together, far from home.

I think there were remains of about 40 members of the 129 who were lost, and they did find that four of them didn’t have the Y chromosome. That caused quite a stir in the academic world for a few months.

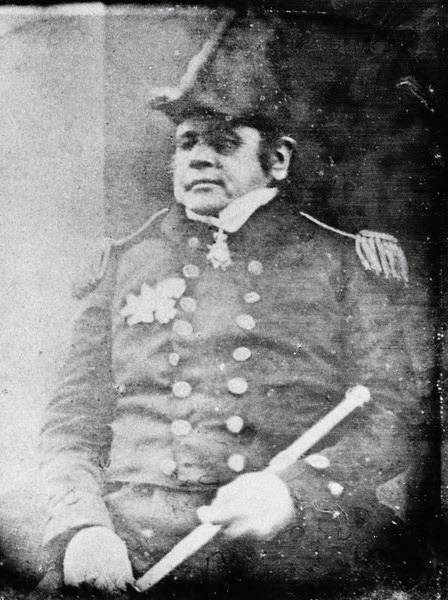

While the initial voyage returned to Britain safely, the book was always fated to end with the tragedy of the ship’s last expedition, led by Sir John Franklin. It left England in May 1845 and was last seen in July of the same year. Information was gradually pieced together as explorers, scientists and native Inuit people found evidence of the ship being stuck in ice, and the crew dwindling in brutal conditions. A particularly unlikely discovery was that some of the remains seemed to be female.

“I think there were remains of about 40 members of the 129 who were lost, and they did find that four of them didn’t have the Y chromosome. That caused quite a stir in the academic world for a few months. Some said it’s because the DNA had degraded, and it doesn’t mean much, but there were women who went to sea, including a woman who fought at the Battle of Trafalgar. It’s been generally dismissed, but they’ve kept the door open, and look at the way Erebus got written, just out of a little bit of information about Hooker. I hope there are lots of things in the book that make people think: ‘I’d like to know a bit more about that.’ I really want readers to be like myself; the more research I did, the more I realised it was a great story.”

The Erebus is now the property of Canada, where the wreck is still being explored. “It’s not too far down, but there’s a very short window every year - they have to work over a six week period - and some years it’s iced over completely, so you can’t get down”, explains Palin. “There are no plans to raise it, because it’s quite well-preserved by the cold water. Now they’re just seeing what they can find, so something’s going to happen each year. I can’t wait to see what they find next.”

Erebus: The Story of a Ship is published on 20th September 2018.