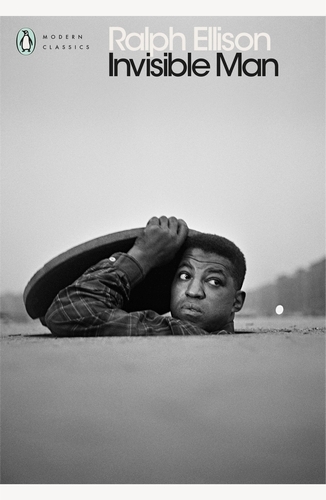

‘What did I do to be so black and blue?’ – Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Read an extract from Ralph Ellison's 20th century classic Invisible Man, a novel that explores the state of African American life at the cusp of the Civil Rights movement: a life of both conspicuousness and dehumanising invisibility.

Now I have one radio-phonograph; I plan to have five. There is a certain acoustical deadness in my hole, and when I have music I want to feel its vibration, not only with my ear but with my whole body. I’d like to hear five recordings of Louis Armstrong playing and singing ‘What Did I Do to Be so Black and Blue’ – all at the same time. Sometimes now I listen to Louis while I have my favorite dessert of vanilla ice cream and sloe gin. I pour the red liquid over the white mound, watching it glisten and the vapor rising as Louis bends that military instrument into a beam of lyrical sound. Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of being invisible. I think it must be because he’s unaware that he is invisible. And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his music. Once when I asked for a cigarette, some jokers gave me a reefer, which I lighted when I got home and sat listening to my phonograph. It was a strange evening. Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around. That’s what you hear vaguely in Louis’ music.

Once I saw a prizefighter boxing a yokel. The fighter was swift and amazingly scientific. His body was one violent flow of rapid rhythmic action. He hit the yokel a hundred times while the yokel held up his arms in stunned surprise. But suddenly the yokel, rolling about in the gale of boxing gloves, struck one blow and knocked science, speed and footwork as cold as a well-digger’s posterior. The smart money hit the canvas. The long shot got the nod. The yokel had simply stepped inside of his opponent’s sense of time. So under the spell of the reefer I discovered a new analytical way of listening to music. The unheard sounds came through, and each melodic line existed of itself, stood out clearly from all the rest, said its piece, and waited patiently for the other voices to speak. That night I found myself hearing not only in time, but in space as well. I not only entered the music but descended, like Dante, into its depths. And beneath the swiftness of the hot tempo there was a slower tempo and a cave and I entered it and looked around and heard an old woman singing a spiritual as full of Weltschmerz as flamenco, and beneath that lay a still lower level on which I saw a beautiful girl the color of ivory pleading in a voice like my mother’s as she stood before a group of slaveowners who bid for her naked body, and below that I found a lower level and a more rapid tempo and I heard someone shout:

‘Brothers and sisters, my text this morning is the “Blackness of Blackness.” ’

And a congregation of voices answered: ‘That blackness is most black, brother, most black . . .’

‘In the beginning . . .’

‘At the very start,’ they cried.

‘. . . there was blackness . . .’

‘Preach it . . .’

‘. . . and the sun . . .’

‘The sun, Lawd . . .’

‘. . . was bloody red . . .’

‘Red . . .’

‘Now black is . . .’ the preacher shouted.

‘Bloody . . .’

‘I said black is . . .’

‘Preach it, brother . . .’

‘. . . an’ black ain’t . . .’

‘Red, Lawd, red: He said it’s red!’

‘Amen, brother . . .’

‘Black will git you . . .’

‘Yes, it will . . .’

‘Yes, it will . . .’

‘. . . an’ black won’t . . .’

‘Naw, it won’t!’

‘It do . . .’

‘It do, Lawd . . .’

‘. . . an’ it don’t.’

‘Halleluiah . . .’

‘. . . It’ll put you, glory, glory, Oh my Lawd, in the WHALE'S BELLY.’

‘Preach it, dear brother . . .’

‘. . . an’ make you tempt . . .’

‘Good God a‐mighty!’

‘Old Aunt Nelly!’

‘Black will make you . . .’

‘Black . . .’

‘. . . or black will un‐make you.’

‘Ain’t it the truth, Lawd?’

And at that point a voice of trombone timbre screamed at me, ‘Gitout of here, you fool! Is you ready to commit treason?’

And I tore myself away, hearing the old singer of spirituals moaning, ‘Go curse your God, boy, and die.’

I stopped and questioned her, asked her what was wrong.

‘I dearly loved my master, son,’ she said.

‘You should have hated him,’ I said.

‘He gave me several sons,’ she said, ‘and because I loved my sons I learned to love their father though I hated him too.’

‘I too have become acquainted with ambivalence,’ I said. ‘That’s why I’m here.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Nothing, a word that doesn’t explain it. Why do you moan?’

‘I moan this way ’cause he’s dead,’ she said.

‘Then tell me, who is that laughing upstairs?’

‘Them’s my sons. They glad.’

‘Yes, I can understand that too,’ I said.

‘I laughs too, but I moans too. He promised to set us free but he never could bring hisself to do it. Still I loved him . . .’ ‘Loved him? You mean . . . ?’

‘Oh yes, but I loved something else even more.’ ‘What more?’

‘Freedom.’

‘Freedom,’ I said. ‘Maybe freedom lies in hating.’

‘Naw, son, it’s in loving. I loved him and give him the poison and he withered away like a frost‐bit apple. Them boys woulda tore him to pieces with they homemade knives.’

‘A mistake was made somewhere,’ I said, ‘I’m confused.’ And I wished to say other things, but the laughter upstairs became too loud and moan‐like for me and I tried to break out of it, but I couldn’t. Just as I was leaving I felt an urgent desire to ask her what freedom was and went back. She sat with her head in her hands, moaning softly; her leather‐brown face was filled with sadness.

‘Old woman, what is this freedom you love so well?’ I asked around a corner of my mind.

She looked surprised, then thoughtful, then baffled. ‘I done forgot, son. It’s all mixed up. First I think it’s one thing, then I think it’s another. It gits my head to spinning. I guess now it ain’t nothing but knowing how to say what I got up in my head. But it’s a hard job, son. Too much is done happen to me in too short a time. Hit’s like I have a fever. Ever’ time I starts to walk my head gits to swirling and I falls down. Or if it ain’t that, it’s the boys; they gits to laughing and wants to kill up the white folks. They’s bitter, that’s what they is . . .’

‘But what about freedom?’

‘Leave me ’lone, boy; my head aches!’

I left her, feeling dizzy myself. I didn’t get far.

Suddenly one of the sons, a big fellow six feet tall, appeared out of nowhere and struck me with his fist.

‘What’s the matter, man?’ I cried.

‘You made Ma cry!’

‘But how?’ I said, dodging a blow.

‘Askin’ her them questions, that’s how. Git outa here and stay, and next time you got questions like that, ask yourself!’

He held me in a grip like cold stone, his fingers fastening upon my windpipe until I thought I would suffocate before he finally allowed me to go. I stumbled about dazed, the music beating hysterically in my ears. It was dark. My head cleared and I wandered down a dark narrow passage, thinking I heard his footsteps hurrying behind me. I was sore, and into my being had come a profound craving for tranquility, for peace and quiet, a state I felt I could never achieve. For one thing, the trumpet was blaring and the rhythm was too hectic. A tom‐tom beating like heart‐thuds began drowning out the trumpet, filling my ears. I longed for water and I heard it rushing through the cold mains my fingers touched as I felt my way, but I couldn’t stop to search because of the footsteps behind me.

‘Hey, Ras,’ I called. ‘Is it you, Destroyer? Rinehart?’

No answer, only the rhythmic footsteps behind me. Once I tried crossing the road, but a speeding machine struck me, scraping the skin from my leg as it roared past.

Then somehow I came out of it, ascending hastily from this underworld of sound to hear Louis Armstrong innocently asking,

What did I do

To be so black

And blue?