- Home |

- Search Results |

- John le Carré on The Night Manager and other adaptations of his books

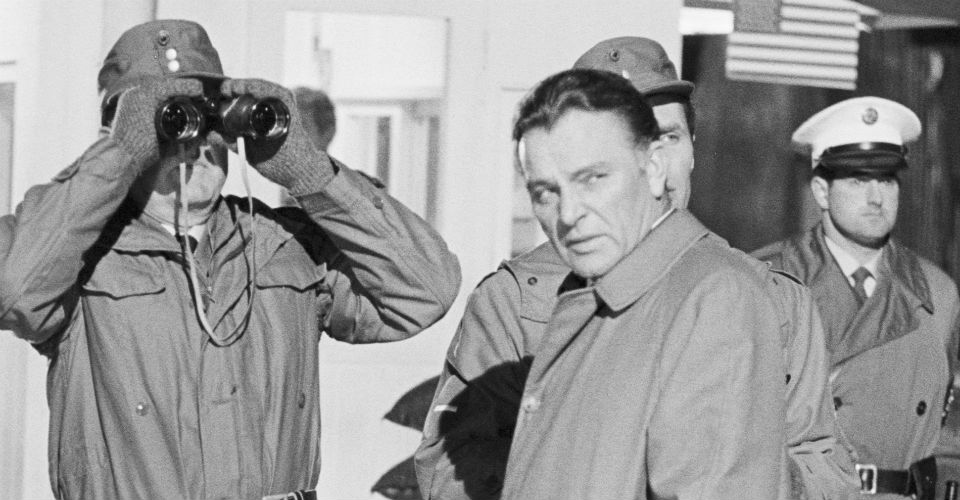

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold provided me with my first experience of the film trade, and in retrospect it was an unusually benign baptism of fire. The director and I got along fine. I enjoyed an amiable relationship with the screenwriter, who as a former instructor in the black arts at a British spy school during the Second World War turned out to know much more about espionage than I did. No great liberties were taken with my story – although I no longer see that as a criterion – and my only job was to provide the odd grace note to the screenplay while befriending Richard Burton and keeping a beady eye on his alcohol consumption

It was an old-style studio movie. Almost everyone in the unit was a full-time studio employee. Over the camp fires at night, old hands regaled me with steamy tales of Clark Gable and Dorothy Lamour. The director, Ritt, was an angry leftist who still bore the unhealed wounds of the Hollywood blacklist. The open hostility between director and star, with Richard Burton cast as the feckless lotus-eater and Ritt as the injured unforgiver, fed Burton’s sense of alienation and gave force to his performance.

And the journey from book to film was a glide: the story a single, if tangled, thread, with an avenging hero headed for his own destruction, and an innocent female victim waiting for hers. Ritt wanted the book as it stood, got it, and made it superbly. What more could a writer ask? Filmmaking was clearly a service industry. You write it, they film it, job done. Or so, in my innocence, I may have thought.

My second experience of the trade, which followed hot on the first, brought me smartly to earth. The book in question, my firstborn, was Call for the Dead, but the studio reckoned the title too spooky for a movie audience and rechristened it The Deadly Affair.

The book’s structure was always fishy, but I vaguely assumed the makers would fix that with a bit of help from me. In the event, the director, Sidney Lumet of Twelve Angry Men fame, expressed not the least desire to meet me, let alone discuss the film he proposed to make. James Mason was cast as George Smiley, but for contractual reasons had to be called Dobbs.

The nearest I came to the thrill of the shoot was eating cucumber sandwiches with Mason at the Ritz Hotel in Piccadilly. If there was a grand opening somewhere, I never got to hear of it. When the movie finally came to a cinema near me, I treated myself to a ticket one afternoon and watched it alone. It had a cast to dream of: James Mason, Maximilian Schell, Simone Signoret, Harry Andrews, Roy Kinnear – not to mention a beautiful young Scandinavian actress who to my astonishment stripped naked, which in the Swinging Sixties was a kind of necessary dare. The sight of her so impressed me that I left the cinema thinking of little else. When I came to my senses, I had an impression of an assembly of nicely shot cameos that didn’t quite add up. Had Lumet read my book? Maybe he had. And maybe that was the problem.

A novel that takes a dozen hours of patient reading is to be transformed into a film that takes a hundred minutes of impatient viewing

Since then some fifteen of my novels have found their way to the screen, either as feature film or television. But the transition remains as unpredictable to me, as frustrating and rewarding, as it ever was. I’ve seen fictional characters that I have spent loving years writing about turned overnight into cardboard. I’ve seen two-dimensional walk-on characters from the edge of one of my novels appear magically enlarged and remade. I have watched scenes from my novels where I sweated blood to crank up the tension, fall flat on their faces for sheer want of the most elementary stagecraft. I have seen some of my dullest, least achieved writing brought vividly to life by splendid direction and acting. In the beginning was the word. The writer lives or dies by it. To the filmmaker, in the beginning was the image. The creative battle has raged happily ever since the first movie flickered into life. What have I learned? That any author who goes into a script conference seeing himself as the guard dog of his novel is wasting his time. The reasons are so obvious they’re silly. A novel that takes a dozen hours of patient reading is to be transformed into a film that takes a hundred minutes of impatient viewing.

The most the novelist can ask is that somehow the arc of his story survives and the audience will leave the cinema having met some of the characters, and shared some of the emotions, that the reader experienced when he closed the book.

And that’s already a big ask. The novelist is an egomane who refuses to delegate his job to anyone. He invents his own characters, dresses them, voices them, invests them with appetites, weaknesses and mannerisms. He creates scenes for them, sets them in whatever location takes his fancy, by day or night, in whatever season of the year. He can decide to be one minute the omniscient voice of God, and the next step down into the story and be part of it.

As to budget: well, a ream of middleweight A4 copy paper these days comes in at six or seven pounds. After that, in my case, it’s the spiralling cost of rollerball refills. For the movie, start around the twenty million dollar mark and work upwards.

The makers showed [Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy] to an invited audience at BAFTA ... If anyone had put a bomb under the building, we’d have lost half the top brass of British Intelligence

Now look at the job of the luckless screenwriter who is adapting a novel of 450-odd pages. Studio executives are too highly paid to read books. Minions provide them with what they call coverage, which is movie jargon for précis. Five pages are enough, thank you, and no fancy words or long sentences.

But the screenwriter can’t make do with coverage. He is paid (highly as a rule) to wade through the entire book and, as the trade has it, pick the fly-shit out of the pepper. This achieved, he will be required by his producers to provide a treatment, setting out his intended march route, which when it comes to writing the actual screenplay he will almost certainly ignore. This may be because, after the first rush, he forgets what’s in the treatment. Or it may be because he discovers that, put to the test, the treatment is as much of a headache as the original novel.

But there’s also a darker reason why a screenwriter may take off on his own. Rather than adapt an intractable novel, he decides to impose on it a better one of his own invention, one he’s been nursing in his head for years but somehow never got around to putting on paper. I’ve watched that happen a few times, and it ends in tears.

So what movies from my work, if any, do I remember with pleasure, even pride? The good news is, bad movies get forgotten in a day; whereas bad books, if you happen to have written one or two, have a way of coming back to haunt you long after you thought you’d forgotten them; not least because there’s always some smart new critic out there who insists that your worst work is your best.

Pleasure? Pride? In the case of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, yes to the pride, no to the pleasure. My brief passage with the troubled, brilliantly talented Richard Burton left behind a sadness that was accentuated by his early death. The harshness of his relationship with Ritt, for all the creative usefulness it may have had, has not faded with time.

The movies I like best to remember – crass as it may seem – are those that were the happiest in the making. Not laughter all the way: not that kind of happiness at all. But movies where director, cast and crew came genuinely to relish what they were making; where the inevitable squabbles and rivalries gave way to a larger, shared purpose.

The first – and chief – of these remains for ever the BBC’s production of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, with Alec Guinness in the lead, which gathered a near-mystical groundswell as the seven-month shoot ran on. When it was done, the makers showed the whole piece to an invited audience at BAFTA – four episodes before lunch, three afterwards. If anyone had put a bomb under the building, we’d have lost half the top brass of British Intelligence. And they loved it. So did I. Even Alec – eternally hard to please where his own work was concerned – loved it.

And as a footnote: the feature film of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, with Gary Oldman as George Smiley, seemed to enthuse its makers in the same eerie way. It wasn’t until The Constant Gardener came along that I – and I believe its makers – felt the old buzz. I had always loved writing the book: from the first furtive soundings of disaffected employees of Big Pharma in London, to forages among the industry’s white chimneys of Basel, and finally to the tribal villages of Kenya, where young mothers who could barely read were being bamboozled into signing ‘consent forms’ that made guinea pigs of their own children.

The film’s producer, Simon Channing Williams, felt as passionately as did our Brazilian director, Fernando Meirelles, that the film had something important to say. With Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz to help them, they said it; and, having said it, set up a much-needed clinic in the slums of Kibera, and a much-needed school on the shores of Lake Turkana. Both thrive to this day. The script – now by adding to the original story, now by subtracting from it – took its own weird course, but somehow the arc survived and so did the passion. And along the way, Rachel Weisz won a well-deserved Oscar.

She won’t be your Mr Burr, she’ll be our Mrs Burr, shrewd, gutsy, dour, sparkling and heavily pregnant throughout the movie

Up till now, these two movies were pretty much the highpoints of my in-and-out relationship with the trade.

I had misgivings when I learned that The Night Manager was to become a six-hour movie for television, updated for our times.

I suppose that in an odd way I was shocked, not least because twenty years ago I had given up the movie rights for dead.

The star director Sydney Pollack (Tootsie, Out of Africa, etc) had fallen in love with my novel and persuaded the studio to buy it for him. Robert Towne of Chinatown fame was signed to write the screenplay and, in some mysterious fashion I still can’t get a hold of, failed to complete it. Large sums of money changed hands, leaving the movie rights stranded in Hollywood’s vaults; and me – since by common consent the novel was eminently filmable – in a state of grumpy mourning.

Now this.

The television part of it was fine by me. The long form has often suited my work better than feature, and television drama these days, whether from America or Scandinavia or, more rarely, from Britain, is scaling new heights.

But a novel I had written nearly a quarter of a century ago reset in present time? With none of Pine’s trip to northern Quebec in the story? None of Central America? My beloved Colombian drugs barons replaced by Middle Eastern warlords? No zillion-dollar luxury yacht for Richard Roper? A new ending to the story, yet to be discussed? What did that mean?

Oh, and by the way, if it’s all right by you, David, we’ll be turning your leading investigator into a woman. She won’t be your Mr Burr, she’ll be our Mrs Burr, shrewd, gutsy, dour, sparkling and heavily pregnant throughout the movie, which is fun because in life, as in the movie, she’ll be pregnant too.

To all of which, a lesser being such as myself might reasonably have responded: why not write your own bloody novel? With all those changes, what’s left of mine?

And the answer, surprisingly, is: a great deal is left, more than I dared hope.

Take Mrs Burr. All right, in the novel she was a man; a rough-cut, ponderous, no-nonsense fellow, but a man for all that, and a throwback to my own distant days in the secret world when female agent-runners were a rarity; or if they weren’t, I never met one. But did we really want this in 2015? One white male middle-aged man pitched against another white middle-aged man and using a third, younger, white middle-aged man as his weapon of choice?

Then there was the agony of Richard Roper’s yacht. I loved that yacht. In the novel, we spend a lot of time on it. It’s Roper’s headquarters. It keeps him offshore. It makes a wicked Flying Dutchman of him. I’d been a guest on a very rich man’s yacht, and I’d watched him run the world from it.

But luxury yachts, it seems, cost the earth to hire, and in movies – unless you’re going to sink them – they quickly become claustrophobic. Far better then, for the movie, to give Roper a billionaire’s island in the sun with a palatial Gatsby-style villa at its centre and a sprinkling of cottages for his underlings and protectors.

Well today, of course, I wish I’d written her into my novel instead of her ponderous husband

As to Mrs Burr: well today, of course, I wish I’d written her into my novel instead of her ponderous husband. But I hadn’t, and that was then. So all I could do, still guardedly, was welcome her to the family and hope to heaven that the writer, director and producers had the wit to conjure an enjoyable and believable character into life.

And they did. Enter Olivia Colman.

And as the script grew under David Farr’s capable hand – I had seen and admired his stage productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford – and as I listened from afar to the progress of the four-month shoot, and was even treated now and then to snippets of film, I began to feel the buzz, those little churnings of the stomach that give an early warning of the excitement to come. From snippets of footage – rushes – you learn one thing at most if you’re lucky: that you’ve got a director you can trust. Susanne Bier was instantly that director – not simply because she was known to be very good and had an Oscar to show for it, but because from the first clips she announced her meticulous style of storytelling, and you knew you could sit back and join her, rather than wait uneasily to trip her up.

Gradually the dramatic triangle begins to emerge – or is it a quadrangle? Hugh Laurie as Roper versus Tom Hiddlestone as Pine. And Jed, played by the peerless Elizabeth Debicki, as the prize. And the fourth member? Corkoran, the Iago of the piece, or better perhaps the Bosola, played by Tom Hollander, the devil with all the best lines.

By now I am simply part of the audience, because this isn’t the film of the book, it’s the film of the film, which is what we all pray for, and it seems to me that this time round we may really have got it: film doing its own job, opening up my novel in ways I didn’t think anyone had noticed – and maybe I hadn’t noticed them myself, which is what happened to me with the BBC’s version of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and happened again with The Constant Gardener.

Then a few days ago I finally get to see the whole movie, three hours in the evening, three the next morning. And what I like best of all is how Susanne Bier goes on chewing at the bone of the drama long after other directors would have given up; and how, in this back and forth interaction between film and book, a two-way process occurs, as I begin to spot in her film things she herself may not be aware of, just as she has spotted things in my novel that I may not have been aware of.

Does she realise, for instance, that in her film Richard Roper goes down winning? He does to my eye, anyway. Even thrashing around in the back of the police van on his way – is it to the gallows, or to the Reichenbach Falls? – he comes over as a fellow who, for all the awful things he’s done, has been hard done by in return.

Maybe that’s because Hugh Laurie’s Roper has been entertaining us for so long with his cool, his wit, his urbanity and his sheer wickedness that we don’t want to let him go. Or maybe it’s because we’ve taken to wondering by now whether Jonathan Pine isn’t enjoying himself a bit too much in his role of avenging angel. Whether Pine’s sins, put together, are not in their own way on a par with Roper’s?

Has Susanne Bier really thought that one out, I ask myself? Or is this just a case of two superb British actors of a certain class subconsciously giving out an aura of insuperability, of a complicity that extends beyond the rational into the homoerotic? Put another way, are Pine and Roper mutually aware of their purposes from the very start? At moments it almost seems so: as if Roper actually enjoys being a partner in his own destruction, just for the pleasure of pairing with someone as intelligent and ruthless as himself; almost as if he’s a little in love with his own executioner.

Did I really get all that into the novel? I’d like to think I did. But if I didn’t, my thanks to the movie for doing it for me.

John le Carré, 2016