- Home |

- Search Results |

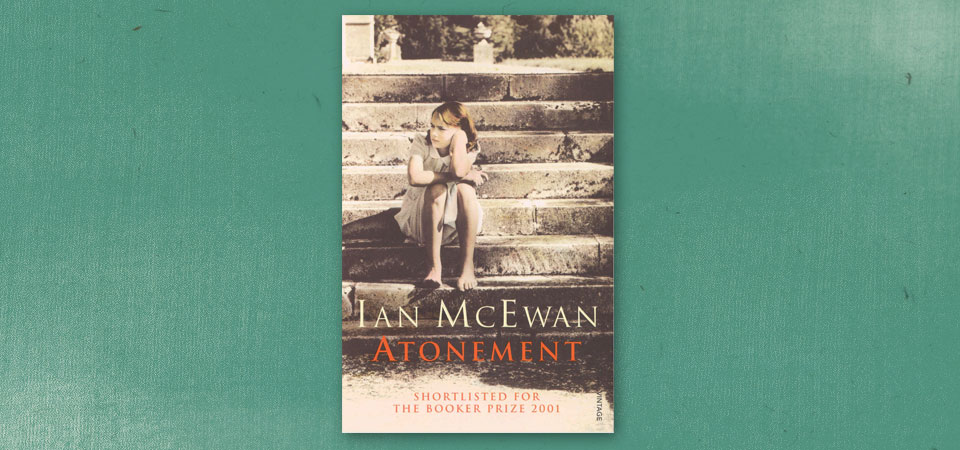

- Ian McEwan on Briony Tallis

Briony was fashioned out of the spare rib of her older sister, Cecilia. The younger Miss Tallis began life as a bit-player. The very first writing I did for Atonement was the present Chapter Two. I wrote out a couple of paragraphs in a notebook – a young woman comes into an elegant drawing room in search of a vase for the wild flowers she's just gathered. Outside, tending the rose beds, is the gardener, Robbie. Cecilia is torn – she wants to see him, she wants to ignore him. And if she ignores him, she wants him to know about it.

At this point I knew almost nothing about the novel I was about to start. I even thought it might be set a couple of centuries into the future. Abandoning that idea, I eventually fashioned a chapter – it is more or less, after scores of revisions, what stands now. And as it developed, I wondered how this complicated, unstated relationship might be made even more complex by the meddling interventions of a younger sister.

A dangerous imagination

I knew nothing about this younger girl until I gave her, in the very first sentence I wrote in my notes, a passion for writing plays to perform in front of her family, and out of that, a desire to become a writer. It's rare to have an entire character in front of you when you start a novel. Characters walk towards their creators, as if emerging from a mist – rather like Robbie does towards the end of Chapter 14. Briony just grew. As events thickened around her and she responded, she took on shape. This is a circular, recursive process. It soon became apparent that her imagination was the element that would disrupt and eventually ruin the love between Cecilia and Robbie.

'I never thought of her as a wicked person'

Despite the sentence that opens Chapter 13 ('Within the half hour Briony would commit her crime.'), I never thought of her, as some readers do, as a wicked person. When she wrongly accuses Robbie of raping Lola, she is guilty of a mistake rather than intentional mendacity. Her imagination has her in its grip. By the time she is 18 she is a hard-working, dedicated nurse, and her remorse for what she has done is just beginning. In old age, Briony recalls 'that busy, priggish, conceited little gir' as she watches the play she wrote decades before finally brought to the stage.

And what exactly is her atonement? She cannot undo what she has done. But she can, however, live the 'examined life'. Over her lifetime she has written many versions of the story that won't let her go. This was her 'fifty-nine year assignment'. The reader has possession only of the final version, the one that deliberately invents and distorts in order to re-unite the lovers that she once, as a foolish little girl, irrevocably forced apart.