- Home |

- Search Results |

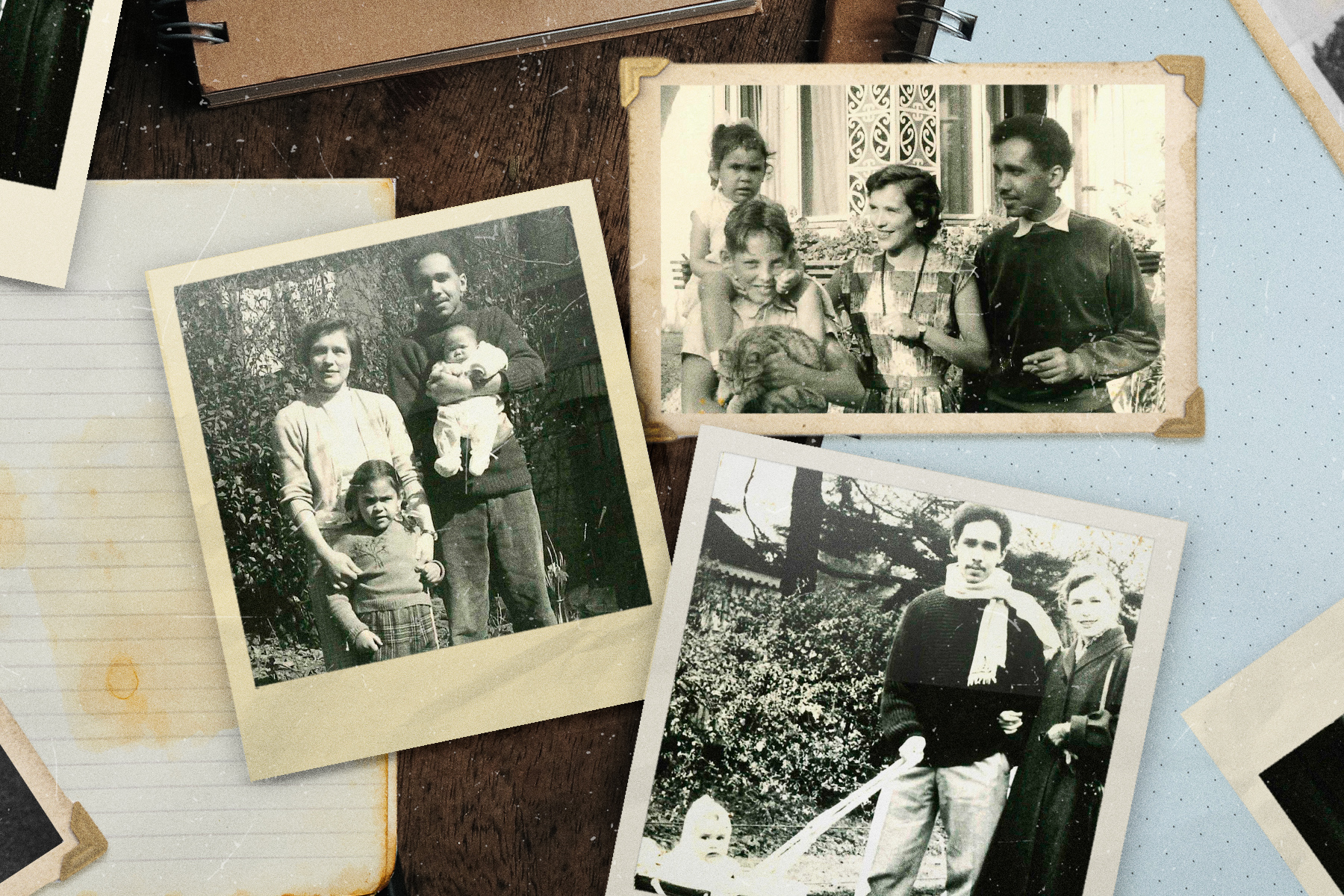

- ‘The Murderer only took him six weeks’: Roy Heath’s sons remember their father

Roy Heath’s haunting portrait of mental illness, The Murderer, won the Guardian Fiction Prize when it was published in 1978. As the novel Colm Tóibín calls "a masterpiece" is republished, the late Guyanese author’s sons remember what it was to be raised by him.

Rohan: One of the abiding memories of my childhood is that of my father lying in bed, fervently writing, sometimes for days or weeks on end. When occasionally he did emerge from the bedroom, it was usually in his pyjamas and to eat with us. The only other things that might coax him away from his writing were a game of chess or to play the piano, both of which he excelled at. Sometimes, if I was lucky, he might also take me to play cricket in the local park, his pyjamas still peeping out from beneath the hem of his trousers as he bowled me out.

Roy Jr: We didn't see much of dad on the weekend because he was upstairs in his bedroom writing, reading and listening to classical music. He wrote longhand in exercise books in an attractive script, and you could tell at what stage of a novel he was by the sounds coming through the bedroom door. After a few months the music would be replaced by the thunderous clacking and pinging of his Olympia typewriter – I remember I would look up the stairs and there would be a secret rush of euphoria, because the hard work was done, and a new novel was on its way! Years later, friends told me they thought my dad was incredibly lazy because whenever they visited, he was always in bed.

Rohan: It was during one of these intense writing stints that he wrote the novel for which he became best known, The Murderer. It took him only six weeks.

The first novel that my father had published was A Man Come Home, in 1974. Proudly presenting my mother with a finished copy of the book, he encouraged her to read it and tell him what she thought of it. A couple of weeks later, she reported back to him: she had found it somewhat boring. Instead of taking offence, my father asked her therefore what kind of novel she might enjoy reading. "How about a murder story?" she replied. And so The Murderer was born.

Dad liked to drink with the Guyanese artist Aubrey Williams and other intellectuals at The North Star pub in Swiss Cottage, but probably his closest friend was Uncle Lloyd, who lived in Wood Green and was a fellow Georgetonian, from Guyana’s capital. Lloyd had storytelling superpowers, and everyone would lean in to listen and end up rolling around on his living room floor at his absurd – if true – tales from back home.

Everything Dad experienced and everyone he met found their way into his writing. One of us three kids might tell a story about a happening in a friend's house and it would suddenly appear in his next novel, leaving us with that fleeting feeling of “Hey, that's my story!” During the long summer holidays Dad would disappear off to Guyana to visit his mother, do research and to refresh his memories of Guyanese life. On returning he would bring back treasures – a set of Arawak arrows or 200-year-old Portuguese bottles scooped out from the mud at the bottom of a canal.

'My father’s novels served as a portal to the country of his birth and the inner workings of his mind'

Rohan: For my father, writing served as a connection to the Guyana of his youth. He used it to bask in his past; to embody what – as an émigré – he had left behind. His pen was the conduit through which he channelled memory, serving it up to the reader as both comedy and tragedy.

When, in his later years, he revisited post-independence Guyana, he complained to me that it was a country much changed. Now, many years after his death, I would argue that his stories serve not just as a chronicle of his personal memories, but also as one of that specific time and place that was British Guiana of the 1930s to the 1950s.

For me, my father’s novels served as a portal both through which to access the country of his birth and to glimpse the inner workings of his mind – he was a very private man, so these insights were valuable gifts to me. Through them, I was able to step into a humid world of tropical myth, hilarity and murder. Into a world populated by characters so vividly drawn, yet at the same time so understated, that as a reader it was impossible not to believe that they actually existed. And all this from the comfort of our small, North London semi.

Roy Jr: Of all his books, The Murderer and the comedic Kwaku are my favourites, because it is through them I can hear his voice and wit most clearly again.

Rohan: Even now after all these years, as I re-read The Murderer, I am struck by the brevity of its prose; every sentence counts, not a word is wasted. Galton Flood, the protagonist, was a character brought to life and immortalised by the swirl of my father’s hand, the same hand that so often checkmated me or hit a six in cricket.

When, as an adult, I finally visited Guyana, it was a country that I immediately recognised and with which I felt intimately familiar with. A country that resonated in me. And for that I am deeply grateful.

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Penguin