- Home |

- Search Results |

- Remembering Shirley Hughes: children’s authors and illustrators choose their favourite illustrations

Remembering Shirley Hughes: children’s authors and illustrators choose their favourite illustrations

Shirley Hughes was a gentle giant of children's literature, breathing life into characters and stories that defined childhoods for generations. Here, five authors and illustrators reflect on her work.

With her first published illustrations appearing in 1952, Shirley Hughes' work has charmed three generations of children. No wonder, then, that when the sad news of her passing broke last week, social media was awash with her charming creations: of Alfie's yellow wellies, beds filled with teddy bears, autumn leaves and, of course, Dogger – the beloved toy who nearly leaves home by accident.

Enchanting but never twee, Hughes' drawings captured childhood like few others before or since. Combined with her ability to capture the big dramas of little lives, she was an author who fundamentally understood and respected the importance of being a child. More than 10 million copies of 200 books illustrated by Hughes sold throughout her career, and yet the imprint she left was arguably far beyond metrics: that of storytelling.

To celebrate her work, we invited children's illustrators and authors to choose their favourite Hughes illustration and tell us what it meant to them.

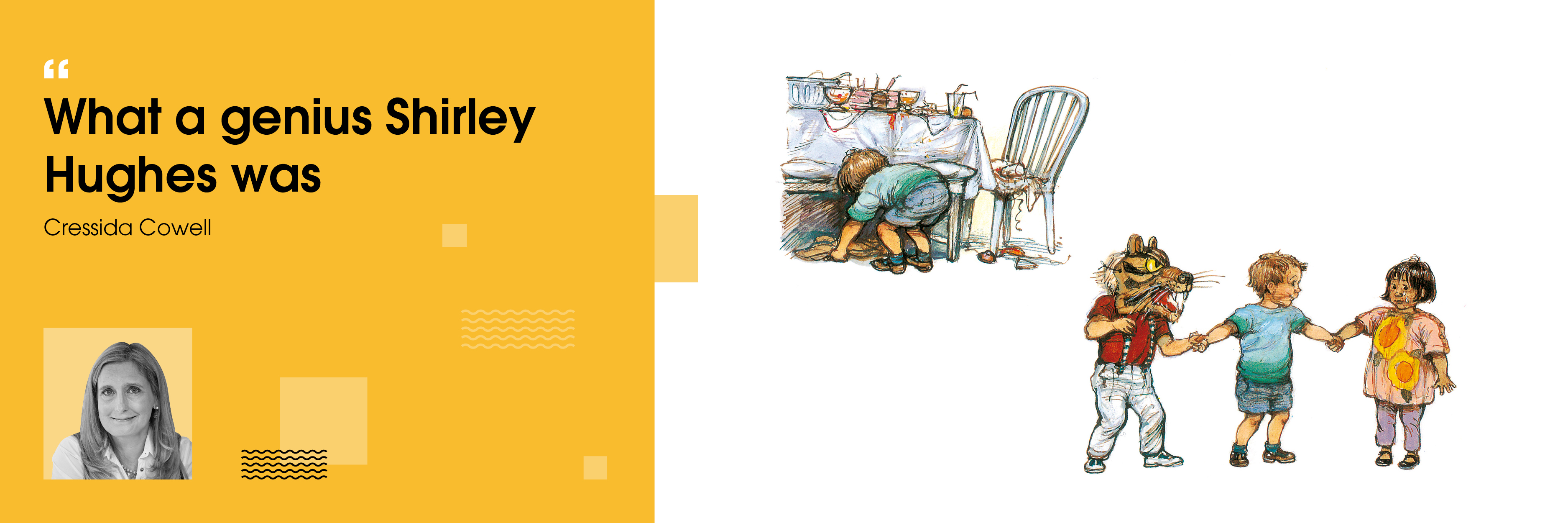

Shirley Hughes was a true legend in our field, and it is extraordinarily difficult to choose one favourite illustration out of so many. But the one I have picked is this double page spread from Alfie Gives a Hand.

These five illustrations are a masterclass in empathetic storytelling. In a series of vignettes, Hughes exquisitely portrays all the characters’ emotions and brings the story to a completely satisfying conclusion. Every parent will empathise with Bernard’s mother, exasperatedly trying to Keep It Together, as the birthday party and the birthday boy spiral out of control.

You can see from the way Alfie is holding his blanket how scared he is by her wildly over-excited (and probably hyped-up-with-sugar) son Bernard in his tiger mask, but Min is even more scared, so Alfie puts aside his beloved blanket in order to take Min’s hand. Through the course of the story we have been gently led to understand and remember what it felt like to be a child ourselves, when going to a birthday party on one’s own required the kind of courage that Bilbo Baggins had to find within himself to leave that hobbit hole, so Alfie’s act of bravery and kindness always made me tearful when I read this to my own children.

What a genius Shirley Hughes was, and how beautifully she encapsulated the essence of childhood! Generations of children have grown up with her warm, wise books, and she will continue to move and inspire generations to come.

Cressida Cowell MBE is the author of How to Train Your Dragon, among other books.

Shirley Hughes made me feel safe on every page. Her words and pictures are so comforting and sympathetic, whether you're reading them at seven or 27. I have never seen such a relatable image as when I first saw Alfie's bowl of cereal, splattered with milk and patterned with teddy bears. It was such a satisfying reflection of my everyday life that I thought this magical book-maker must know me personally. Her artwork is beautiful and full of a special sort of genius that speaks directly to the child who is just learning how to process their feelings for the first time. Shirley is a hero of mine, and I will always come back to her work for inspiration and comfort.

Magenta Fox is a children's book designer and illustrator of titles including Weirdo.

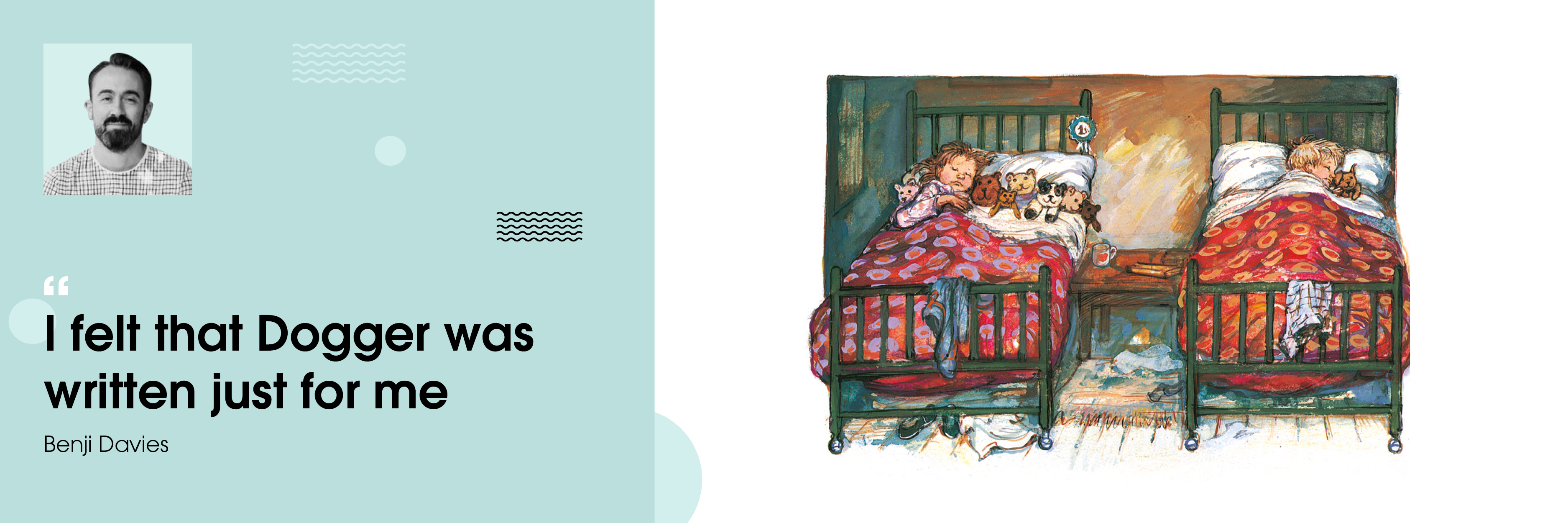

The thing I have always loved about Shirley Hughes' illustrations is the way they make you feel. I particularly love this moment at the end of Dogger, when Dave and his sister Bella are finally cosy in the beds and you know that all is well. It's not only the way Shirley draws and paints these scenes that exudes so much warmth, but the detail she choses and the gentle humour. The pride of the rosette hung on the bed frame, the casually strewn clothes and shoes. Dave’s small hand keeping contact with Dogger while he sleeps. And the smiles on the teddy bears tell us everything.

When I was small I too had a toy dog, like Dave, and I loved this book because I felt that Dogger was written just for me. Shirley’s influence on my own work is likely greater than I will ever know. Thank you, Shirley.

Benji Davies is an award-winning illustrator and author of The Storm Whale among other books.

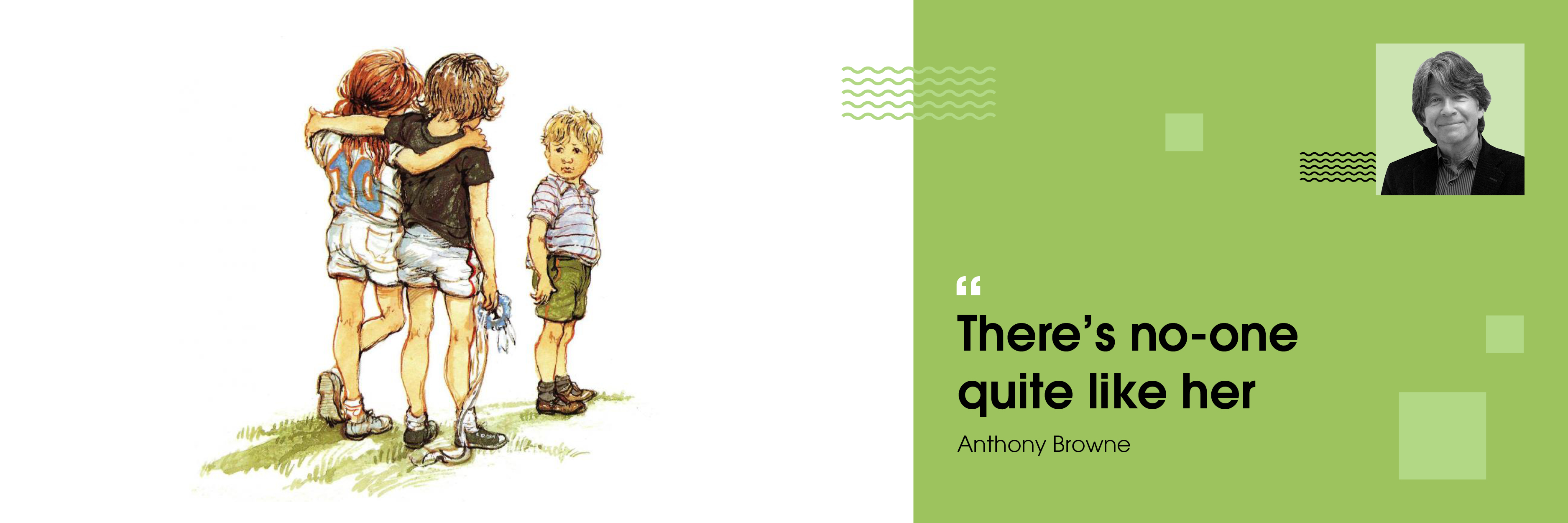

This beautiful, simple drawing from Dogger conveys much of Shirley’s genius. At the school summer fair, two girls try to cheer up Dave, who’s lost his beloved toy dog. We see the back of the leggy girls, hot and sweaty, having just won the three-legged race. They are relaxed and seemingly still entwined together after the race. One casually holds a rosette trailing on the ground, and we can easily imagine their proud but caring faces. Dave just stands there looking at them, showing us exactly how he feels.

The picture is probably not very different to the preliminary sketch that Shirley would have made before she painted the finished artwork. It’s loose and unpretentious, but the body language tells us so much, and the expression on Dave’s face conveys his wretched sadness, bewilderment and much more.

Shirley Hughes drew children’s emotions with compassion, empathy, and wonderful observation. There’s no-one quite like her.

Anthony Browne is the author and illustrator of prize-winning bestsellers such as Gorilla.

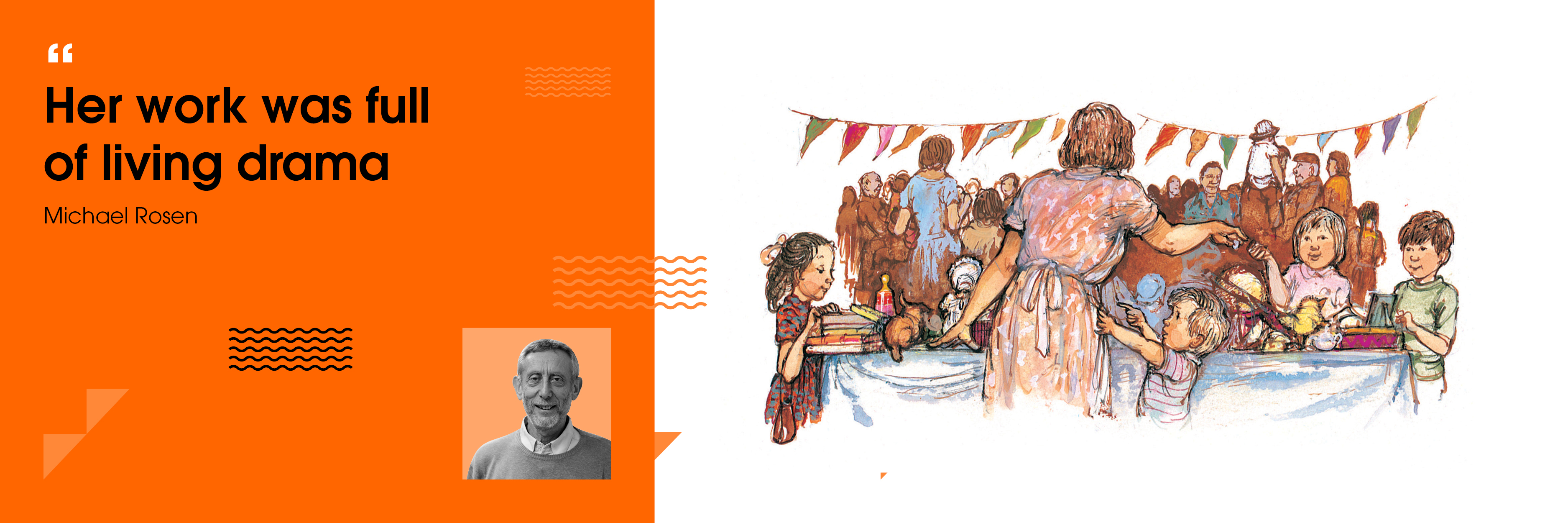

Children’s books are, by and large, reassuring – at least in their conclusions. The point about Shirley’s books is that on the way, they created moments of danger, loss, and, to borrow a frequent family word, “bother”. These are actually big moments, and by that I mean big for very young children, who in Shirley’s worldview are not made insignificant for being very young. Just take one cataclysmic moment from Dogger: Dave has lost his soft toy, and it turns up on a stall at the school summer fair. He tries to explain that it’s his – but no, he has to buy it. But he hasn’t got enough money to buy it. He rushes off to get more money, gets it, but when he comes back, someone else has bought Dogger.

For Dave in the book, and for a child hearing or reading the story and indeed for any empathetic adult, this is a moment of anguish. The work done by readers reading literature is done right here: we make connections between events, thoughts and emotions through metaphors and symbols. Dogger is Dogger, but what Shirley has shown Dogger to be for Dave, and what Shirley shows happens to Dogger, means a lot more. And being detached is a feeling that isn’t bounded by age, which explains why and how Shirley’s books are, as I say, so intergenerational.

Another way of putting this is to say that Shirley was very knowledgable about children and childhood, but clearly this knowledge wasn’t put into psychology textbooks. It’s in the psychodramas she plays out on the pages of her books. The point about her life drawing is not just that she was good at it, but also that the faces, gestures, body shapes and postures of the children she painted are each full of living drama. We might say that of course they feel very human or that they’re lively, or warm, but their ability to capture tiny but significant changes of mood – irritation, wonder, hopelessness, generosity, cunning – is quite remarkable.

Michael Rosen is a former Children's Laureate. This passage was extracted from a piece he wrote for The Observer.