- Home |

- Search Results |

- Where the Salt Path led next

Where the Salt Path led next

Made homeless in her fifties, Raynor Winn never meant anyone other than her husband to read her account of the long walk that followed. Five years later, she’s written two bestsellers – and started a new adventure on a farm in Cornwall. Alice Vincent visits the author and partner Moth to talk about The Wild Silence, starting again and what it really means to find a home.

Ten minutes after sunrise and the glow has reached the other side of the valley. Mist rises from the creek, frost bright in the orchard. Cider has been made here, near the River Fowey on Cornwall’s southern side, for eight centuries, and now Raynor Winn and her husband Moth are the custodians of these ancient apple trees. This is the view she writes to, first thing in the morning before he wakes up, with a cup of tea to hand.

Winn is an author now, but that wasn’t always the case. She hadn’t written a word until autumn 2016, when she sat down to capture the 630-mile coastal path walk she and Moth undertook a couple of years earlier. Both in their fifties, the endeavour wasn’t a late-onset gap year so much as a last resort: a bad investment and prolonged legal battle had left them homeless. They could sign up for a council house, or take a second-hand tent around the furthest reaches of the UK. They opted for the latter.

The couple’s situation was worsened by Moth’s brutal diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration, or CBD: an incurable degenerative and chronic disease. Still, they walked – and amazing things happened. Moth’s condition improved, drug-free. His memory, though, was fading. So Winn began another marathon, writing a story that became The Salt Path. As she explained in her second book, The Wild Silence: “I could write myself on to the Coast Path and in doing so put Moth right there next to me, so when he read it he wouldn’t just hear the wind, he’d feel it.”

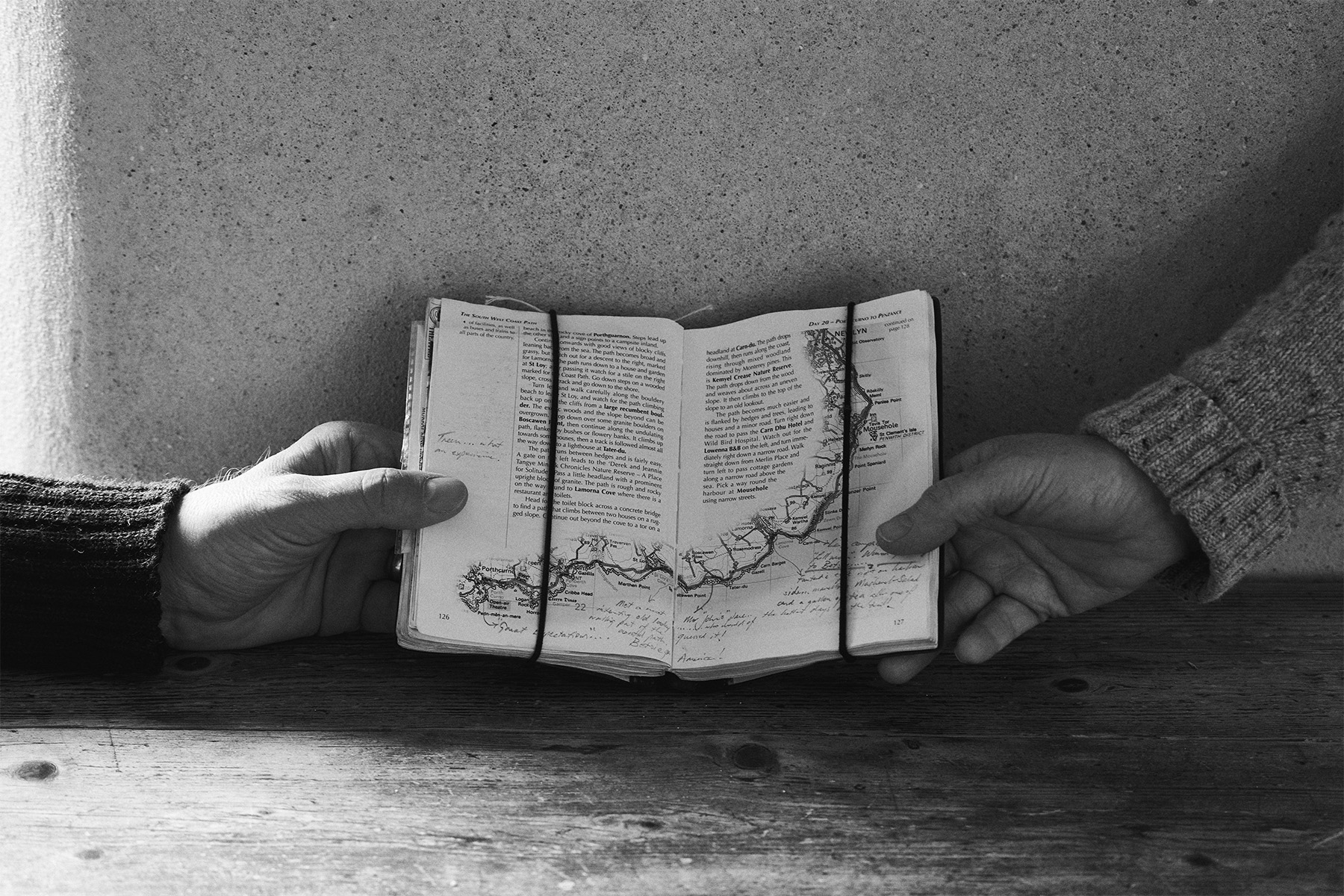

There was only ever meant to be one copy of The Salt Path: printed on fading ink, tied up with string. A birthday gift for Moth. Five years later and it and The Wild Silence, have sold nearly a million copies at home and abroad, with The Salt Path spending nearly two years in The Sunday Times bestsellers list.

I’m visiting Winn to talk to her about it. She still lives in Cornwall, a destination at the end of a couple of trains and a drive flanked by verges of primrose and wild garlic. Winn and Moth are outside their home as the car pulls up, arms and smiles wide, offering the kind of welcome borne of learning what it is to be lost. We chat in the sunshine, Monty, their runt-of-the-litter terrier, excited by our ankles.

Across from the house – handsome against the cresting hill – sits the cider barns. We are here, all of us, because of what The Salt Path brought Winn. Hundreds of readers’ letters and conversations at events and – unbelievably – the offer of a home. “A complete stranger gets in touch and says, ‘I've just read your book, and it felt like a 300-page CV. Do you want to come live on my farm?’” she recalls.

'We really just didn’t trust people. It was quite a barrier to get over'

The farm was, however, a borderline ruin. The owner worked in London and had struggled to restore it as he had intended. In The Wild Silence, Winn describes the house as “oozing like a sponge, sucking up water when it was raining and squeezing it back out when it stopped”. She deals with a “town of mice” in the attic in a feat of athletics and courage that wouldn’t go amiss in a horror film. The land was worse: overworked and lifeless, Winn writes of a silent dusk, devoid of birdsong. “When we came, it was so grim,” she says. Winn speaks softly and with thought. Both she and Moth – teenage sweethearts – carry the Staffordshire accents of their upbringing. “There’s so much agricultural waste,” she continues. "The hedgerows were just dead, there was hardly any wildlife.”

Even broke and without a permanent residence, the decision to take the farm wasn’t an easy one to make. The fall-out from losing their previous home had left deep scars. “We really just didn’t trust people,” she tells me. “It was quite a barrier to get over. But then we came here, and it was so remarkable. We kept coming back. One evening, a deer walked in front of the house and we thought, ‘We’ve just got to do it.’”

That was in late 2019. Barely 18 months later and the Georgian farmhouse is bright and beautiful, fires roaring away and late afternoon sunshine spilling in. The air is ripe with spring birdsong; the first swallows of the year appeared two weeks ago. Pheasants dart across the orchard. The trees are fruiting properly for the first time in years. The cider barns, air thick with apple-steeped wood, are in operation. Winn shows me around and my arms prickle with goosebumps. “There's a real sense of age in here,” she says. “You can really feel that generations, hundreds of years and people have walked in here.” Plans are afoot: for a new press, a place for volunteers to learn and stay on the farm. Winn and Moth have done it all, largely by themselves.

InThe Wild Silence, Winn explores her challenging childhood on a farm, her retreat to the coast path, the complex tug of grief from the death of her mother. “It’s quite a difficult emotion to put across, a connection to nature,” she tells me, sat on a picnic bench in the orchard, tucking her pale hair around neck and away from the wind. “I didn’t have an academic background to bring to it, so I was trying to find a more emotive way to explain it.”

Winn jokes that she wrote much of The Wild Silence on the M5, hurtling between the dozens of events she found herself speaking at in the midst of The Salt Path’s ballooning success. “I thought, I've got so much more to say than just a sequel,” she says. But the books dovetail closely; you could read them in either order. Together, they tell a story of human strength in adversity being supported, rather than challenged, by the extremities of the outdoors.

In originally writing The Salt Path just for Moth, Winn gave the book an irresistible intimacy. To read it is to feel the couple’s hunger, their weary bones, the relentless patter of daily needs that become acute when you’ve lost all else. “My memory is starting to go now so I do read The Salt Path, over and over,” Moth tells me. “It’s like looking at a photograph that you took years ago.” We’re walking up the hill that gives a panoramic view over the valley; the sun is setting, it’s time to take photographs.

Winn’s books have been categorised as nature writing, but while reading I couldn’t help but think of them as love stories. In both, she tenderly captures long-term love, from courtship through elopement and the trials of middle-age. Moth, she writes, is her “thin place… where it all became clear and there was no separation between worlds or time.”

“Yeah, I know what you mean,” says Moth, when I tell him this. “I do feel that when I read it, it touches me every time, it really does.” Homelessness, bestselling book, fortuitous farmhouse: the pair still cling to one another most of all. “I've got a Ray, and every day she gets me up in the morning. And she'll remind me that today is worth living for,” he says, grin spreading across his face.

It’s difficult to read either of Winn’s books without wondering about Moth’s condition; the good news is that the pair continue to put one foot in front of another. This spring, they will walk the length of the UK – from the top of Scotland back to their new home.

For now, once she’s spent the morning writing, Winn will join Moth in his work on the farm, gently restoring the soil to goodness, ushering in the wildlife. Otherworldly piles of sticks are dotted around the orchard – a rarely seen, centuries-old technique for drying out wood he’s brought back. They’ve become such sites of ecological interest that academics from nearby universities have been studying them.

It’s an existence, Winn says, that is similar to that on their farm in Wales, before any of this journey began: “After the madness of The Salt Path to suddenly go back into this way of living is something very soothing, very calm and very real, as well.”

I ask if it feels like home, and she pauses. “I think it possibly does, yeah.” She laughs quietly. “I don't quite feel the same about home now, I don't really associate it so much with house and walls as I did before.” Winn turns her head, looks over the apple trees, across to where the creek lines the valley. “I think it's more to do with what makes you feel like you. And I think you can take that with you no matter where you are.”

What did you think of this article? Email editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk and let us know.

Image: Stuart Simpson / Penguin