- Home |

- Search Results |

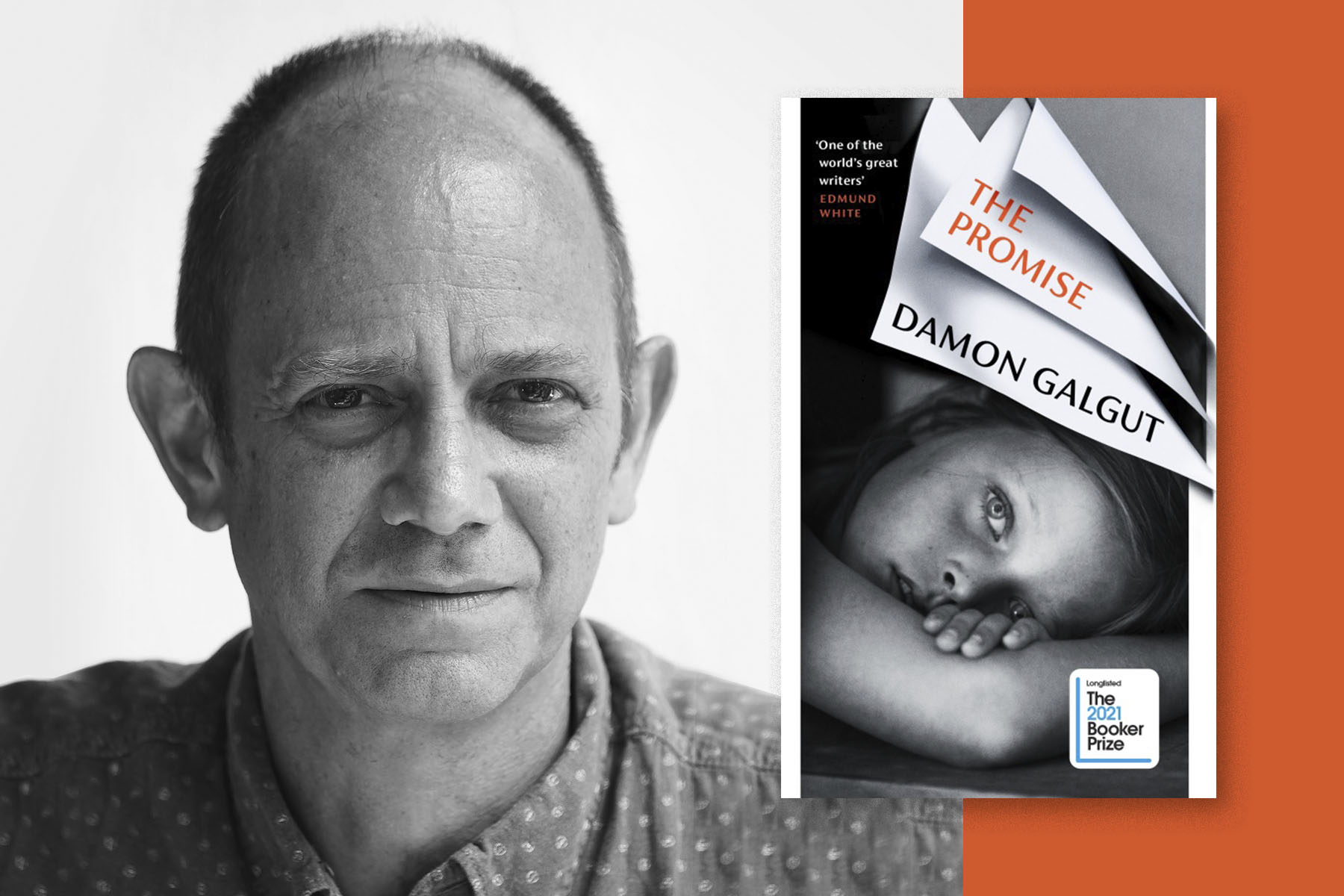

- Lightbulb moments: Damon Galgut on writing The Promise

This week, Damon Galgut won the 2021 Booker Prize for his novel The Promise.

It crowns a career already replete with accolades: many of the South African writer’s novels, reaching back to 2003’s The Good Doctor, have won or been shortlisted for a major literary prize.

Hailed by peers like Tessa Hadley, Colm Tóibín, and Edmund White (who called Galgut “one of the world’s great writers”), The Promise is a tale of family drama, depicting the downfall of a white South African whose promise to their black housekeeper – of her own property, her own land – remains unfulfilled.

Earlier this year, we asked Galgut to speak on the origins of The Promise, from the family dynamics to the “cinematic” inspiration behind the novel’s narrator – not to mention the importance of “ambushing” your audience.

What compelled you to tell this story now?

'I could move fluidly in and out of scenes in the same way a movie camera does'

It’s the burning question at the centre of South African life: who owns the land? Obviously that issue goes back to the day the first Europeans set foot here. But in truth I’m somewhat surprised that this aspect of the novel has overshadowed everything else, because for me it was more of a background theme, a recurring motif I could work through the four sections of the book. I was, I am, much more interested in the family and their internal dynamics. Soap opera over politics any day! Aesthetics over ideology!

The narrative voice inhabits the minds of almost all of the book’s characters at various points. Why did that feel crucial to telling this story?

It became crucial, but didn’t start out that way. In fact, I began with a much more formal, traditional approach, but that quickly became frustrating. Then by chance I put the book aside to do a couple of drafts of a film script, and that diversion changed the way I saw my novel. I realised that there was another way to deal with the narrative; that I could move fluidly in and out of scenes in the same way a movie camera does.

I carried over a few other conventions from cinema too, such as cutting from one character to another without a break, or moving away from the main action to some arbitrary event happening on the sidelines. The voice of the book also moves forward continuously, without a break, in the same way a film runs on to its end. All of this was liberating and exciting, and cause for great anxiety.

What was the hardest part of writing The Promise?

There was no section of the book more challenging than any other, since it’s not a plot-driven novel. You’re seeing the same family at different points in time over four decades, and a lot happens in the spaces between. What became the real challenge was how to hold a reader’s attention, given the segmented structure.

'I like books that require a bit of work from the reader, too'

It seemed to me that language was the answer. The experience of reading it had to be pleasurable on the simplest, most immediate level, which is to say through the use of words. So a kind of poetry was required. And in a more secondary way, the structure had to be continually surprising.

I read an interview with Tom Stoppard a long time ago which kept coming back to me during the writing, in which he spoke about ambushing the audience. I understood that to mean you have to continually wrong-foot your reader, by never going where it seems you might. Even on the level of a sentence, you should try to end up somewhere unpredictable. Of course, it has to be credible and authentic as well as surprising, and that ain’t so easy.

Your novel addresses the reader with implied knowledge of them. Was this to implicate them in the story?

I come from a background in theatre, and the breaking of the fourth wall is a device by now quite well established. It has the effect of breaking the agreement between audience and players that this is somehow ‘real’ and should be studied through glass. For some reason, the novel has always lagged in this department, or so it seems to me. The convention is that if you use a third-person voice, it should be steady in its tone and not rock the artificiality of the edifice. Well, why?

I started to play with the narrative voice and became delighted with the possibilities it opened up. I wanted to stretch its range, from calm scene-setting to direct accusation. Part of ambushing the audience! Because most readers expect to be lulled into a descriptive paralysis, it might be jarring for some, but I like books that require a bit of work from the reader, too. It helps to think of the narrator as a character in the book, who’s never named but always present.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.