- Home |

- Search Results |

- These forgotten childhood books paint a vanishing picture of the UK

When I lived in an urban space, I would romanticise rural areas. Verdant fields and neat, rectangular hedgerows have long been synonymous with our cultural idea of a bucolic idyll, and I would gaze at such areas lovingly, as many still do. But moving to the countryside has allowed me to cultivate a more intimate relationship with the land, and sadly all is not well in paradise.

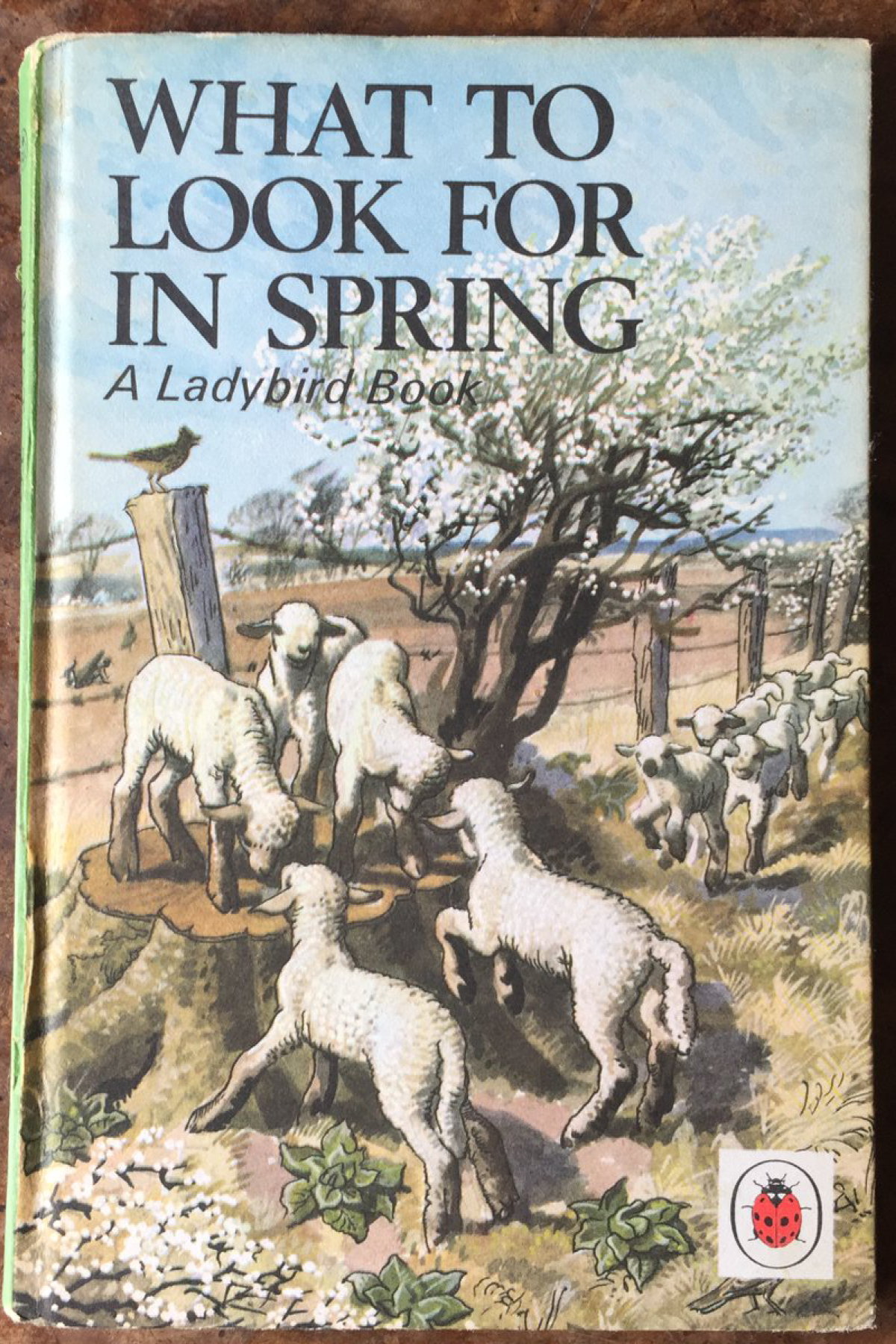

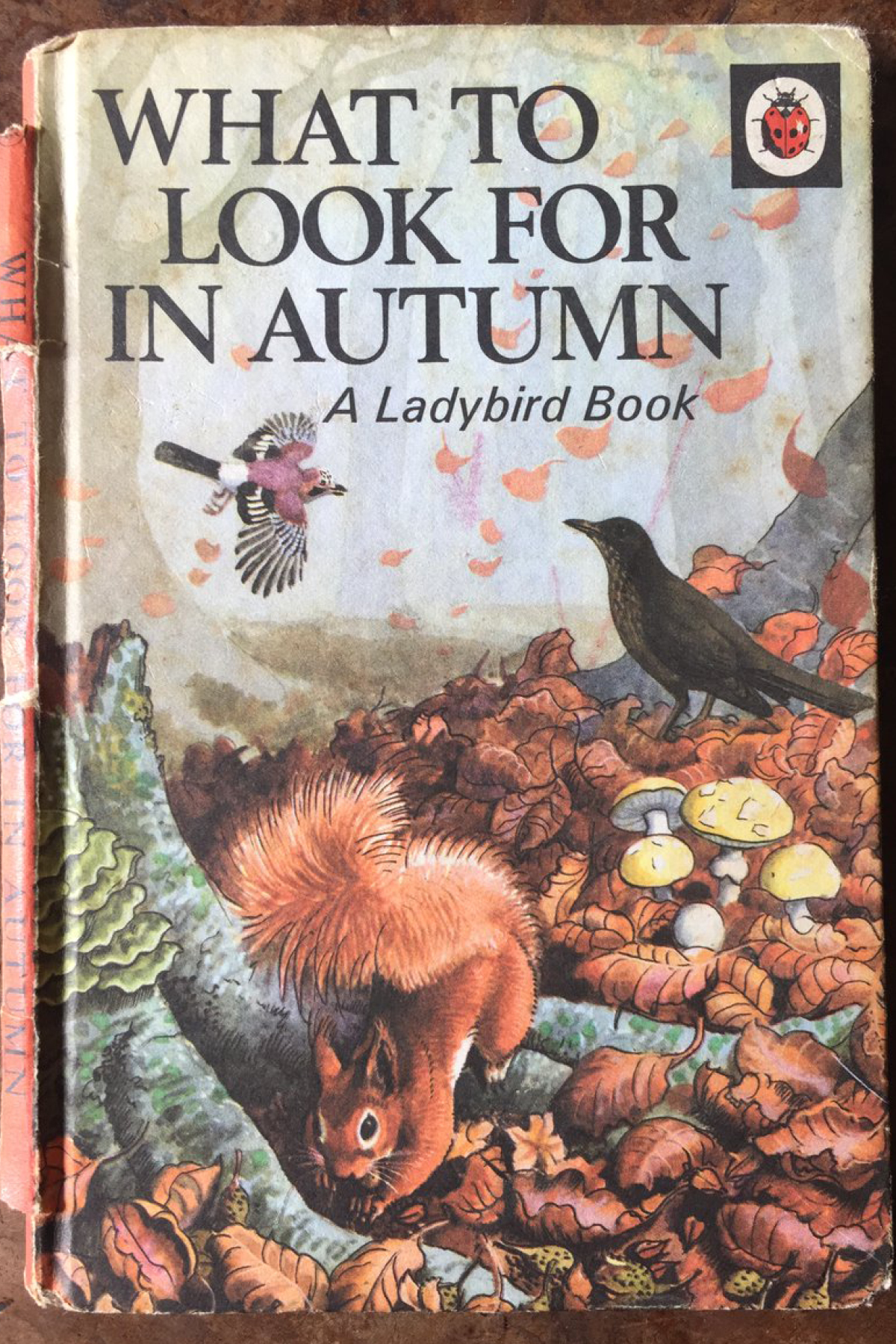

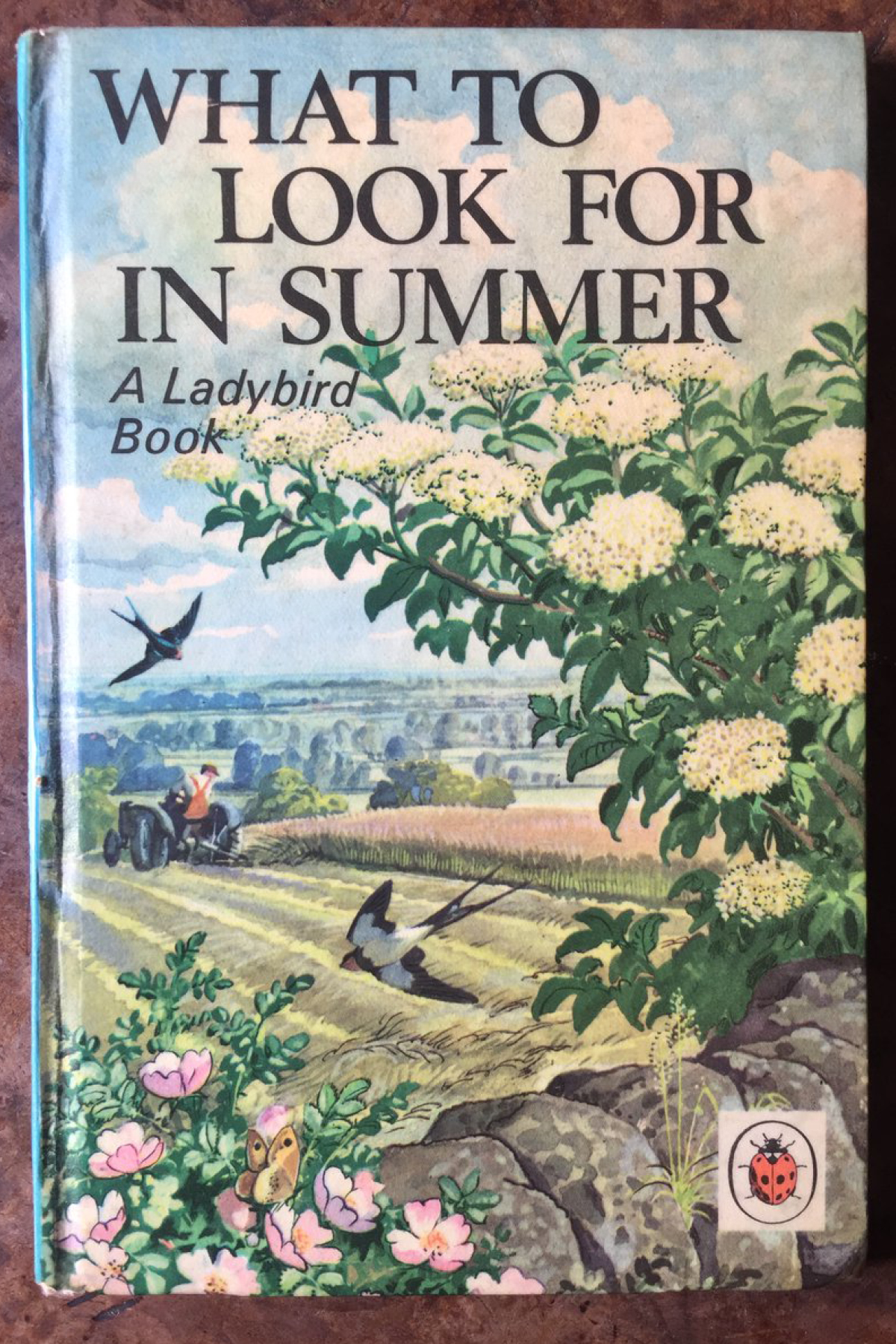

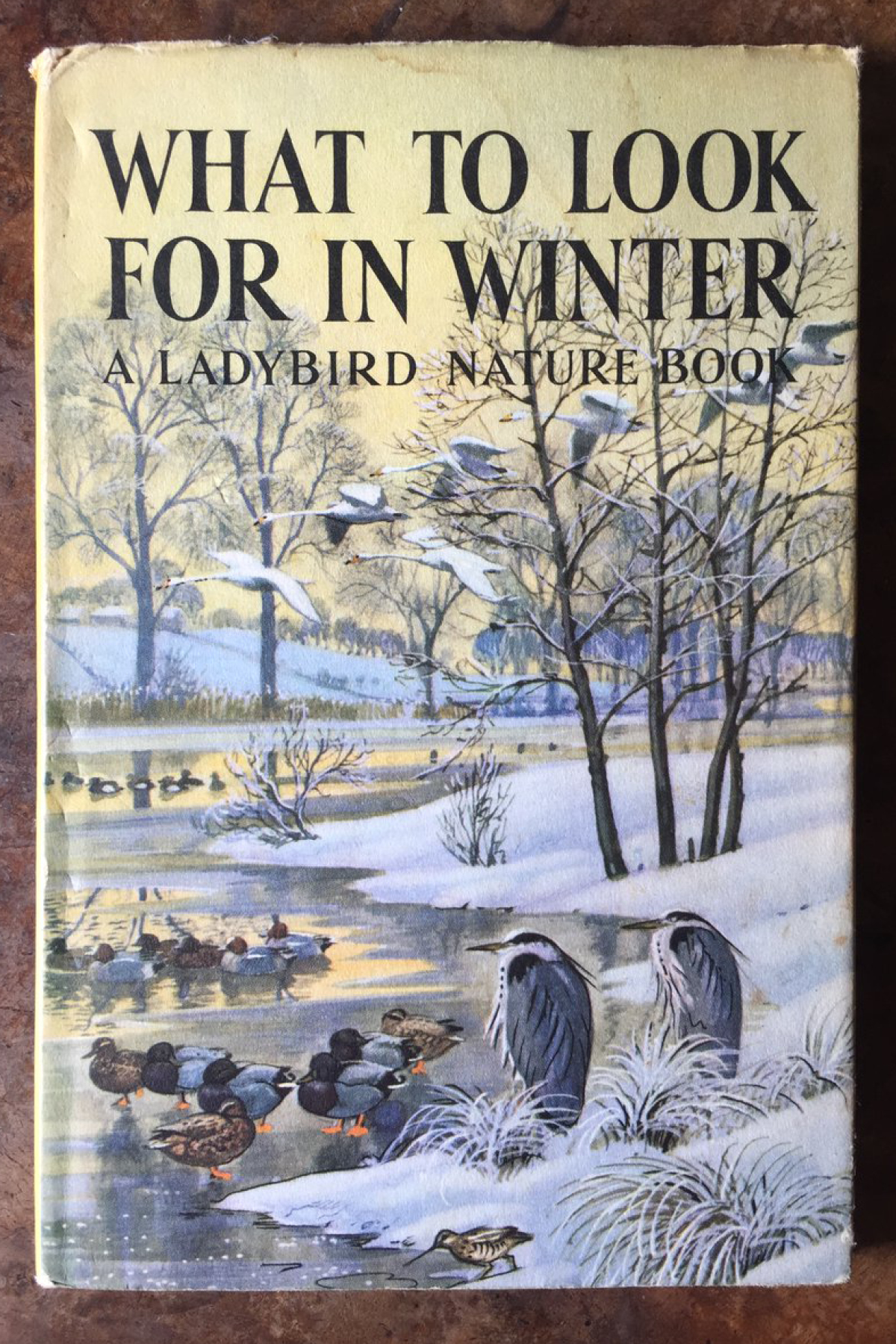

A gift from my mum made it all too salient. When she was a child, she had the What to Look for series of Ladybird Books, written by Elliot Lovegood Grant Watson and delightfully illustrated by Charles Tunnicliffe. Published around 1960, each book is dedicated to a season: Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter, and encourages children to immerse themselves in the natural delights of the changing year. Being interested in nature, I often flicked through the books as I was growing up, and eventually mum decided I should have them instead. They are worn now, the spines peeling and covers soiled, but I have a penchant for old books and find their imperfections charming. And no amount of wear and tear can detract from Tunnicliffe’s beautiful illustrations.

Since the 1970s over 40 million birds have disappeared from our landscape

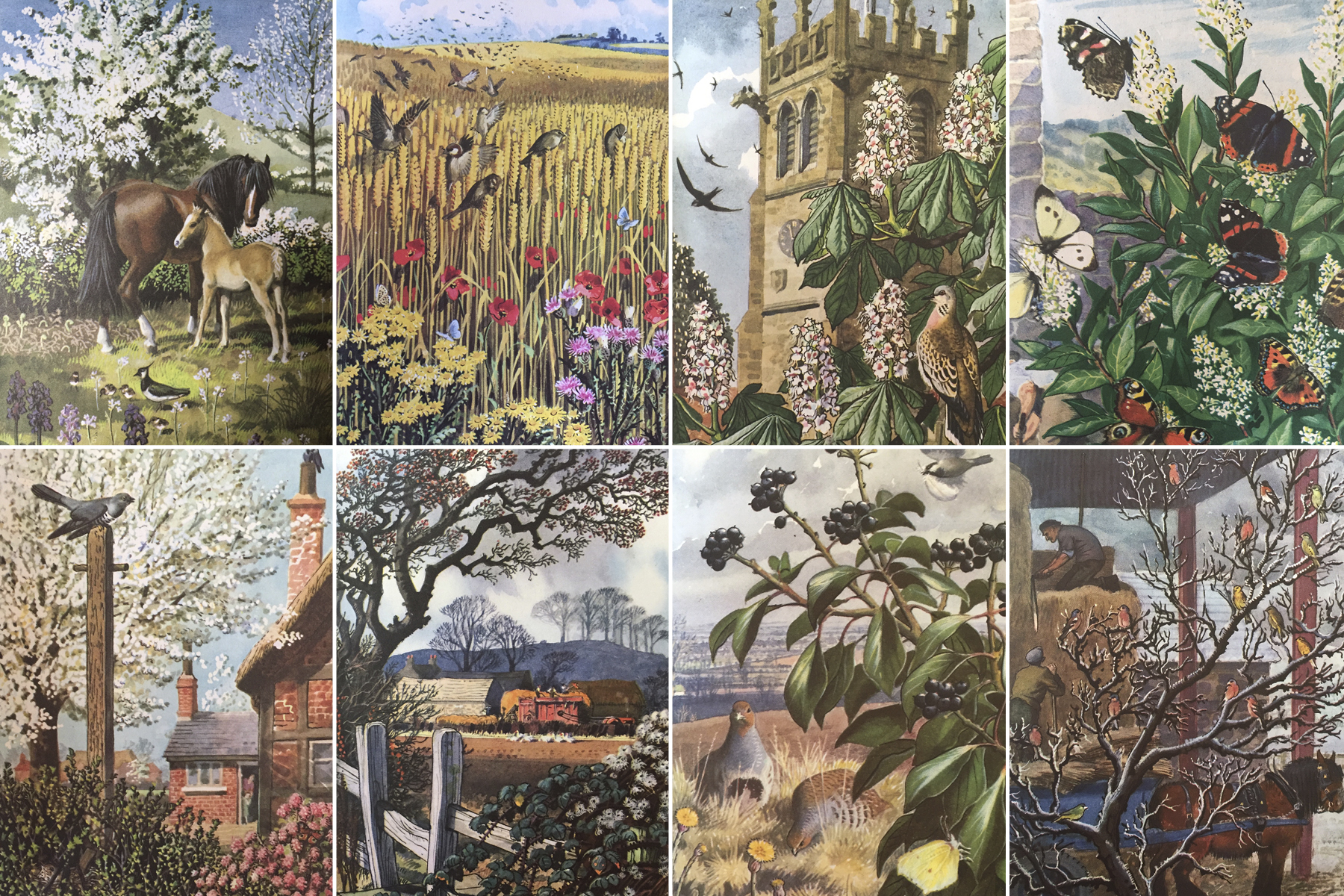

Recently, a misty morning found me flicking through my copy of What to Look for in Autumn, but one illustration made me sit up. There was a rooftop covered in hirundines: swallows, house and sand martins. Beyond them were telegraph wires equally laden with these birds. The words of an elderly neighbour came to mind: “Couldn’t see the wires for the swallows” he’d told me when speaking about days gone by, and in an instant I realised that I wasn’t looking at some fanciful event - this is what Tunnicliffe had actually seen. I flicked further. There were huge flocks of lapwings and swarms of eels. I pulled out the other books in the series. The illustrations showed kaleidoscopic butterflies, flocks of house sparrows hundreds strong within wildflower-edged fields, swifts, grey Partridges, a turtle dove, spotted flycatcher, wood warbler and there, in all his heraldic glory, was a cuckoo, proudly perched on a post in a blossom-filled garden.

I thought back to the last time I’d heard a cuckoo, let alone seen one. It was years ago, yet I used to hear them every May. Further on in Spring I read: ‘By this time the nightingale should be singing’. I only know of one place to hear Nightingales now, and it’s a long way from where I live, but another elderly neighbour told me they used to sing from all the hedgerows when she was a child.

Each page is a poignant window into the past. But I know it’s not been going well for nature. Every year I notice the dawn chorus getting quieter. The official figures are heartbreaking; since the 1970s over 40 million birds have disappeared from our landscape. An average of 835 wrens vanish every single day. And of the 8431 species assessed in the 2019 State of Nature Report, 133 are now extinct. Something is going terribly wrong. Tunnicliffe’s illustrations portray such bioabundance, yet sixty years later the species he depicted in huge numbers are dying out.

Although the reasons are manifold, the bulk of the problem began, and continues, with the industrialisation of farming. Before this, when Watson and Tunnicliffe were growing up, our landscape largely consisted of small, mixed farms where hedgelaying and haymaking abounded. This meant plenty of flowers for insects and food and cover for animals and birds. But nowadays many farms have become huge monocultures doused in chemicals. Haymaking has been replaced with silage (since the 1930s we have lost 97% of our wildflower meadows) and hedges have been ripped up, divided and mistreated, none of which leaves much space for wildlife.

Understandably our country has to produce food, but in a country of self-confessed wildlife lovers, food production at the expense of wildlife seems hideously skewed. We’re taught that big green fields and neat hedgerows look pretty, but the reality is that they are atrocious for wildlife, which needs a variety of habitats to survive; particularly those habitats which are commonly perceived of as messy; such as wetlands, scrubland and areas filled with ‘weeds’.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome means that each generation thinks the amount of nature it grew up with is normal, but as time creeps on our baseline is getting desperately low. The UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world. If Watson and Tunnicliffe were alive today, they’d be horrified by the scarcity of many species, but our children will grow up thinking this is the norm. And if we carry on along this trajectory, their children will think that many of our most beloved species never existed at all. If we don’t let nature come back in all its rambling, chaotic brilliance, the What to Look for series of Ladybird Books will one day look like no more than made up fairytales.

Images: Kerrie Gardner