- Home |

- Search Results |

- Ben Macintyre on Agent Sonya, the Cold War’s most remarkable female spy

Ben Macintyre is no stranger to spies. The bestselling author and historian has won acclaim from John le Carré for his gripping real stories of espionage and intelligence during the Second World War and Cold War. But even he admits the subject of his latest book is somewhat stranger than fiction. “If you stuck her in a novel, people would be like, ‘Nahh, come on that’s much too far-fetched’” he tells me down the phone.

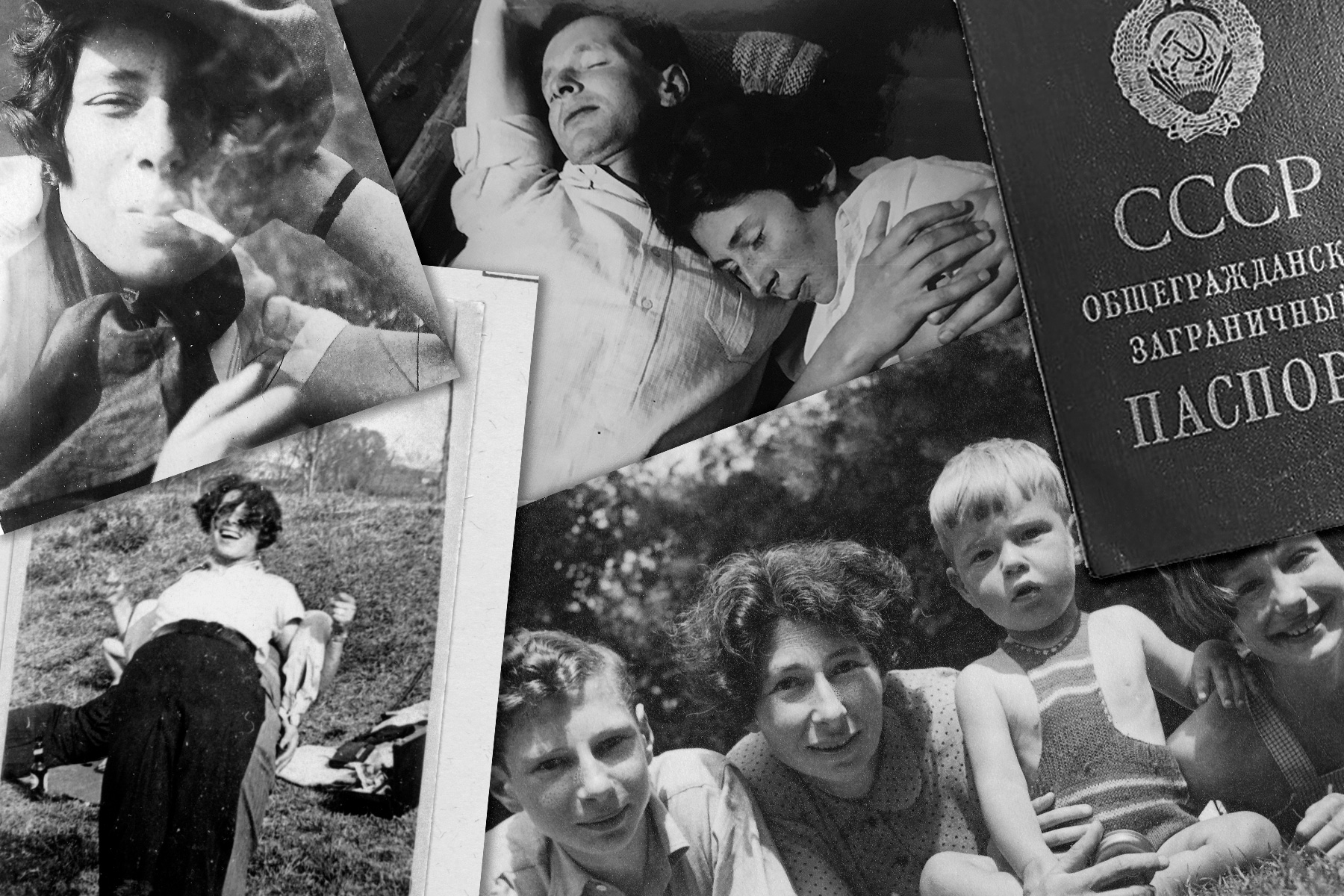

The “rare bird” in question is Ursula Kuczynski – codename Agent Sonya - a German Jew and communist who recruited German spies for America while actually working as a colonel in Russia’s Red Army – all the while raising three children and baking cakes in a sleepy Cotswolds village in the Thirties and Forties. Her neighbours knew her as a master of scones, wholly unaware that in the back garden stood an illegal radio transmitter that communicated directly with Moscow. Her career highlight? The creation of the Soviet atmonic bomb.

In Agent Sonya: Lover, Mother, Soldier, Spy, Macintyre tells Kuczynski’s incredible story across the course of her life, spanning decades and countries in which some of the most momentous events of the 20th century took place. The book, like his 2017 publication SAS: Rogue Heroes, has been picked up for a television adaptation. All the more remarkable, then, is that Macintyre only discovered Kuczynski’s existence by accident.

'Loyalty, love, betrayal, romance and adventure - you get to invade territory that is normally occupied by novelists'

“When I set off on this journey I had no idea what I would find,” he says, explaining that he was researching The Hampstead Spies (“a group of anti-Nazi Germans living in Britain recruited by American Intelligence”) when he found their lynchpin: Kuczynski. “I found this whole other, much bigger story that I didn’t know anything about.” The result started in and ended in East Germany, but took in swinging Shanghai – “simultaneously glamorous and seedy, shiny and grotty,” as Macintyre details in the book – picturesque Austria and sleepy, wartime England in between. There was also plenty of action beyond morse code and leaked documents: Kuczynski’s three children each had a different, equally dashing father. As she said herself of her marital commitments: “I was not a nun”.

“Loyalty, love, betrayal, romance and adventure - you get to invade territory that is normally occupied by novelists,” says Macintyre. “The lovely thing about writing these non-fction narrative stories is that it seems so outlandish and yet it’s all true. It’s all in the records. I make nothing up, I don’t have to.”

Kuczynski died 20 years ago, long before MacIntyre encountered her in his research. But he was nevertheless blessed, as he explained in his Penguin Podcast interview, with an abundance of material about her. “One of the great ironies and pleasures of writing about espionage is that, while it is deeply secretive at the time… in my experience spies are some of the most indiscreet people you’ll ever meet, particularly when they’re in retirement.”

The Kuczynski family was not only extensively tracked by MI5 – to the tune of 71 separate files, although that she was able to operate for so long undetected, escaping to East Germany in 1950 and never returning, is the matter of another story – but by Kuczynski herself. “The way she writes about herself is very vivid and immediate and revealing, and emotional in some ways,” says MacIntyre of her diaries. “She was able to look inside and describe her feelings, and that’s not just rare in [research] it’s hen’s teeth – it doesn’t happen very often.” Another gift was the manuscripts for the autobiographical novels Kuczynski wrote in her final years; while heavily propagandist versions were published in East Germany, the Stasi kept the originals on record. As Macintyre says: “It’s wonderful to find a manuscript that tells you what the officials didn’t want you to know.

But most illuminating were Kuczynski’s children, particularly her eldest son Michael, who “had an amazing memory” and would make factual comments on MacIntyre’s manuscript. Being let into the family – who are based in Germany - was a challenge that paid off unexpectedly, Macintyre says. “They were, understandably, extremely suspicious of me. But after a while they became extremely helpful and by the end of our time they said, ‘Here is our archive, help yourself. This is all yours.”

Michael ‘Maik’ Hamburger, Kuczynski’s son with her first husband, never lived to read the finished book – he died in January at the age of 91. But he left Macintyre with a meaningful encouragement: “He said, ‘I know my mother better than I did before’, the author says. “And that was an amazing tribute, really, I felt rather moved by that – I was able to uncover more than he knew”.

It’s fitting that Kuczynski’s children held the key to her biography, because they were a crucial part of her success as a spy, too. Macintyre describes her motherhood as “her strongest defence as an intelligence agent. She was virtually invisible to the security services: they were all men and they simply couldn’t believe that a woman in an apron could also be a kind of top-level colonel in the Red Army. It just didn’t compute.”

In fact, it took another woman – MI5’s Milicent Bagot – to smell a rat. Bagot was the only person from British intelligence to be suspicious of the “rather large wireless set and… special pole erected for use for the aerial” emerging from the Kuczynski’s house. Nevertheless, Kuczynski – a woman who reached the highest position of authority in any intelligence service – went un-investigated.

'She went to her grave wondering if she’d been a good spy and a bad mother'

Still, that double-life took its toll. “Throughout her life, the struggle between what she saw as an ideological duty and her responsibilities as a mother, a wife, a homemaker, were constantly in tension,” says Macintyre. “In a way she went to her grave wondering if she’d been a good spy and a bad mother.”

It’s this level of complexity – plus the fact that over the course of her life Kuczynski went from “ferocious anti-Nazi campaigner to spying on the West” - that will make the spy a killer role when the small screen version (attached to “quite a famous director”) airs. Macintyre admits he’d love Phoebe Waller-Bridge to play her: “They look not unalike, and Ursula has that slight awkwardness that [Waller-Bridge] lent to Fleabag,” he muses. “I think she’d be brilliant.”