- Home |

- Search Results |

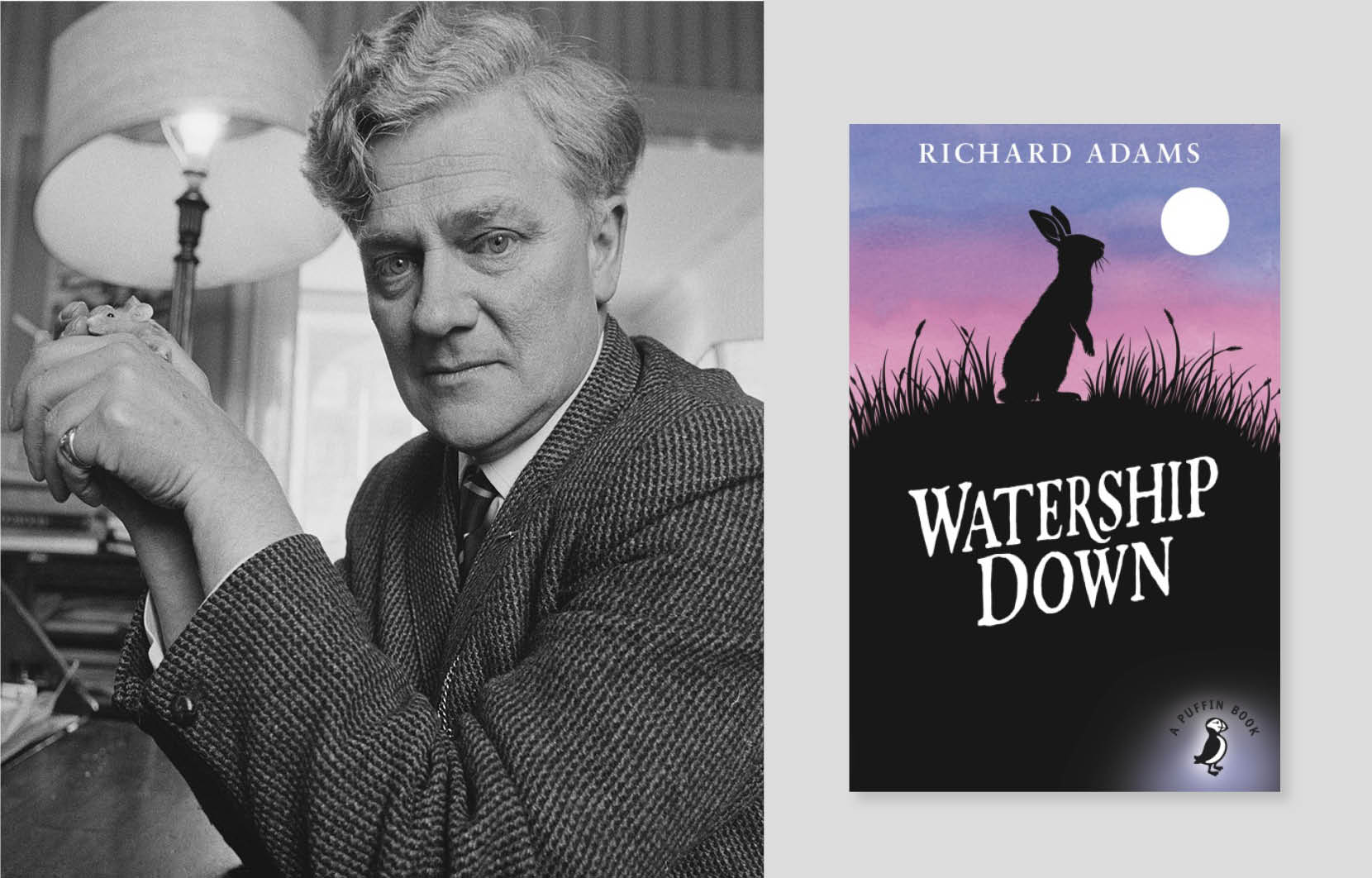

- Richard Adams at 100: the story behind Watership Down

Depending on when your childhood was, the words ‘Watership Down’ may well conjure something fairly vivid.

If you were a child of the Seventies, perhaps you were among the millions who devoured the book. Or maybe you were taken to the cinema to see the infamous 1978 film adaptation, which terrified an entire generation so thoroughly that for the next one, millennials, 'Watership Down' became synonymous with peril. Over the past decade, the image of Watership Down’s cartoon rabbits have been revived for a new generation in meme culture. Nearly 50 years have passed, and Richard Adams' cautionary tale remains starkly relevant. It’s quite amazing to think it was almost never published at all.

Adams, who would have been 100 this week, was a civil servant for most of his life, working in housing, local government and eventually in the Department of the Environment and hailing from Berkshire. He wasn’t, in short, a career writer, saying he ‘never thought of myself as a writer until I became one.’ That was in 1972, when he was in his Fifties, and Watership Down was published and changed everything in children’s fiction.

For the uninitiated, or those still scarred by the film, the book’s plot is relatively straightforward: a rabbit named Fiver has a vision that suggests the future of his warren is unsafe. He leads a group of rabbits away from the apparent safety of their warren to find a new one. Along the way, they encounter the barbarism of man and beast, but ultimately achieve safety, led all the while by Fiver’s ephiphanies.

'I simply wrote down a story I told to my little girls'

Adams, who died in 2016 aged 96, maintained that his story was ‘just about rabbits’, but its winding narrative, elaborately named characters (Hyzenthlay, anyone?) and intricate social structures within the story (one supposed haven transpires to be a police state, and class and sexual politics are folded in as well) have led many to unravel Watership Down as allegory. Part of the reason why Watership Down has endured is because the story it tells has gained new resonance with each passing decade.

And yet, to the frustration of many, Adams maintained that ‘it’s only a made-up story, it’s in no sense an allegory or parable or any kind of political myth. I simply wrote down a story I told to my little girls.’

Yes, despotic baddie General Woundwart’s origins really are that prosaic: Watership Down started on long car journeys as a means of entertaining Adams’ two daughters. The eldest, who was eight at the time, requested: ‘a completely new story, one that we have never heard before and without any delay. Please start now!'. And so Adams responded: ‘I just began off the top of my head: “Once upon a time there were two rabbits, called eh, let me see, Hazel and Fiver, and I'm going to tell you about some of their adventures.”’

It was Adams’ daughters, and their relentless persistence, that encouraged him to get the story down on the page about 18 months later. Seven publishers rejected the finished manuscript; the disappointment became so unbearable that Adams resorted to sending his wife to collect the returned copy. But once it was published, the reviews glowed. Copies sold beyond the original print run of 2,500 by many multiples, making it a near-instant bestseller. Watership Down was similarly popular in the US, where it became Penguin’s all-time best seller, with 50 million copies in print across 18 languages.

More, though, the book transformed Adams, turning him into what he called ‘the person who told those stories.’

And he has remained so. Adams went on to write a further 19 books, among them Plague Dogs and, sequel to his first, Tales from Watership Down. He approved wholeheartedly of Martin Rosen’s 1978 adaptation, but others followed too. A television version crested the millennium on CITV, and, just days before Christmas 2018, a star-studded version descended on the BBC and Netflix.

'Pre-empting the rise of Extinction Rebellion, that latest version felt particularly pertinent'

Pre-empting the rise of Extinction Rebellion and against a backdrop of the rise of right-wing politics the world over, that latest version felt particularly pertinent. Adams may only have wanted to tell a story about rabbits, but it is one that continues to play against the issues of the day. Much of the peril from his book is about the innate brutality of how humankind interacts with nature – it’s the horror of the ensnared Bigwig that has made the 1978 film so grimly memorable. That, said director Rosen, was intentional: ‘That’s part of nature – nature is very tough,’ he told The Independent. ‘Richard [Adams] was very strong on that element. I felt it was absolutely critical.’

And his daughters agreed. 'Daddy didn’t like the way people babied, and pandered to and ‘icky-ised’ children, lying to them about death and so on,' one of them, Juliet, told The Guardian. 'We’re destroying the environment and endangering all the animals – I think it would be strange to ignore that.'