- Home |

- Search Results |

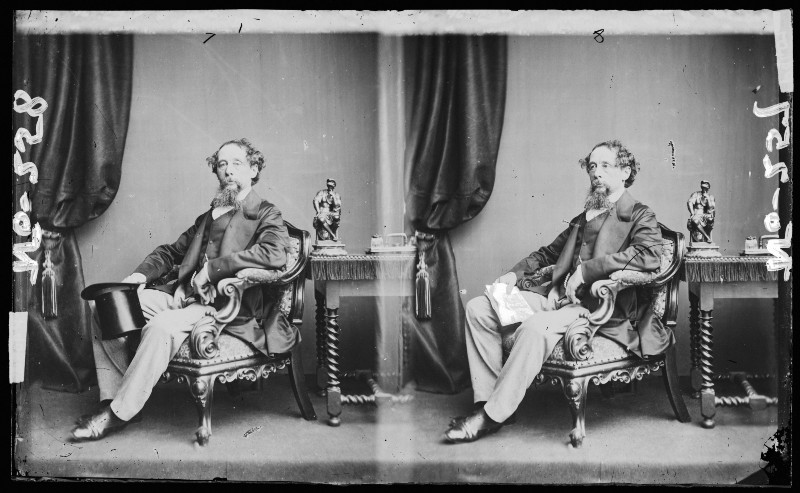

- An overlooked Charles Dickens novel shows the writer at his madcap best

Charles Dickens wrote an immense amount very quickly, often with unrealistic deadlines. It is one of the many pleasures of his early novels that you can so often see this chaos preserved in the text. The Pickwick Papers remains perhaps the greatest ‘variety show’ novel ever written – deliberately set up as a series of improvised and chaotic escapades, with an exuberant sense that neither the reader nor the writer has any idea what is going to happen next. His next novel, Oliver Twist, is carefully plotted, but again has traces of its origins as a serial preserved in its pages, with occasional outrageously boring or contrived bits of filler still slapped in to hit a deadline. Perhaps the novel that best reflects Dickens’ crazy productivity and over-commitment is The Old Curiosity Shop.

It preserves at least three train-wrecks. The book kicked off as a short story in Master Humphrey’s Clock, but then broke free of this limitation, forcing Dickens to drop its opening pages. It then remained narrated by ‘I’ (Master Humphrey), whose dullness immobilises the story and is simply dumped at the end of chapter three for a third-person narrative. Dickens then seemed, having settled upon calling it The Old Curiosity Shop (in itself, of course, a wonderful title), to have gotten bored with the shop and spontaneously packed his characters off on an immense chase across England, with the shop losing its central role and any right to being the novel’s title.

Yet, this mayhem is what makes the novel so enjoyable. The plot itself is chaotic and in the end banal (oh no – a long lost relation!), but once any hope for narrative coherence is thrown out the window, the reader can relax and simply fall in love with the sheer page-by-page perversity and strangeness of the book. Little Nell is often laughed at as an antiseptic bore, but her dullness is another decision of genius, as she is the still point around which some of the most fabulous grotesques in all literature turn. As in Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens seems to tap some deep well of perversity to come up with such horrors as Nell’s grandfather (surely one of the greatest descriptions in all fiction of a man whose brain has been eaten by gambling), Sampson and Sally Brass and, of course, the horrifying Quilp.

It is one of the many pleasures of Dickens' early novels that you can see chaos preserved in the text

Quilp ultimately takes over the entire novel. Unlike some of the other characters in the chase, he knows that Little Nell has no secret fortune; he pursues her and her grandfather across the country purely out of malice. He revels in his own awfulness, and by the time of the fantastic chapters in the waxworks – between his terrifying treatment of his wife, the great scene where he screams at a chained-up guard-dog and (perhaps the summit of Dickens breaking free from all realist constraint) the scenes in his revolting Thameside lair (particularly the one where he happily sits drinking boiling alcohol) – he has already become a demon rather than a human.

The narrative itself is filled with the most extraordinary, exuberant descriptions of life on the road in England at the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign. The sections at the racetrack, the schoolroom, the factory (an early intimation of Hard Times), the Punch-and-Judy show, the waxworks, plus pubs as funny and terrible as those in Pickwick Papers – what more could anybody want from a novel? And I have run out of space for Dick Swiveller, one of Dickens’ greatest written confections, burbling away in an inventive, bizarre and hilarious language that can only exist on the page.

At the time, The Old Curiosity Shop turned Dickens from being merely a sensation to being a sensation with no rival. So much of what he later wrote remains deeply etched in the popular imagination, but it is this novel – freewheeling, preposterous, fiendish, hilarious – that best demonstrates and preserves just why Dickens was loved so much.

A description survives of Dickens in this period working frantically away in his Covent Garden offices with different projects on different desks. He employed a boy to come in at regular intervals with a bucket of cold water. Dickens would plunge his head in the water, stand upright, give himself a shake and then keep on writing.