- Home |

- Search Results |

- How Georges Simenon reinvented the detective novel with Maigret

How Georges Simenon reinvented the detective novel with Maigret

Hyper-prolific yet critically adored, the Belgian writer took crime novels into new terrority with his 75 books series – newly translated this week – winning devoted fans from Muriel Spark to Alfred Hitchcock in the process.

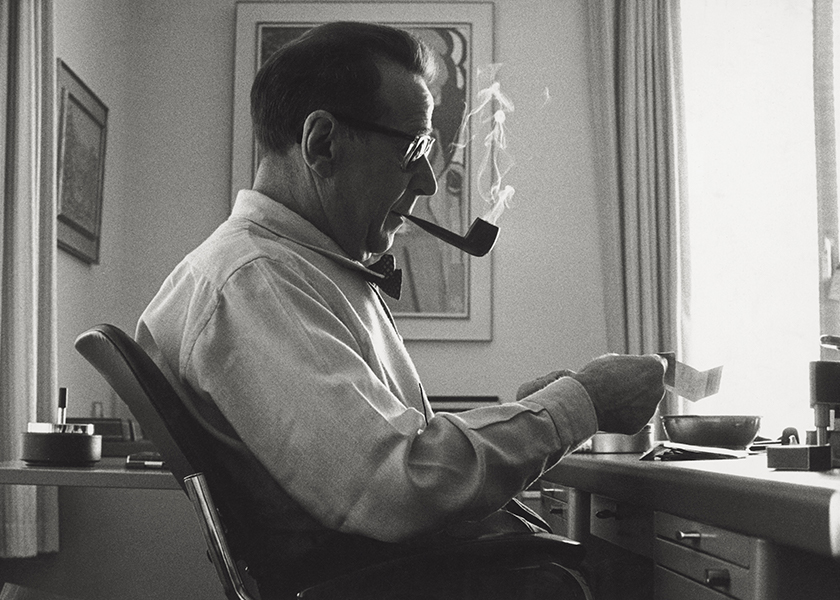

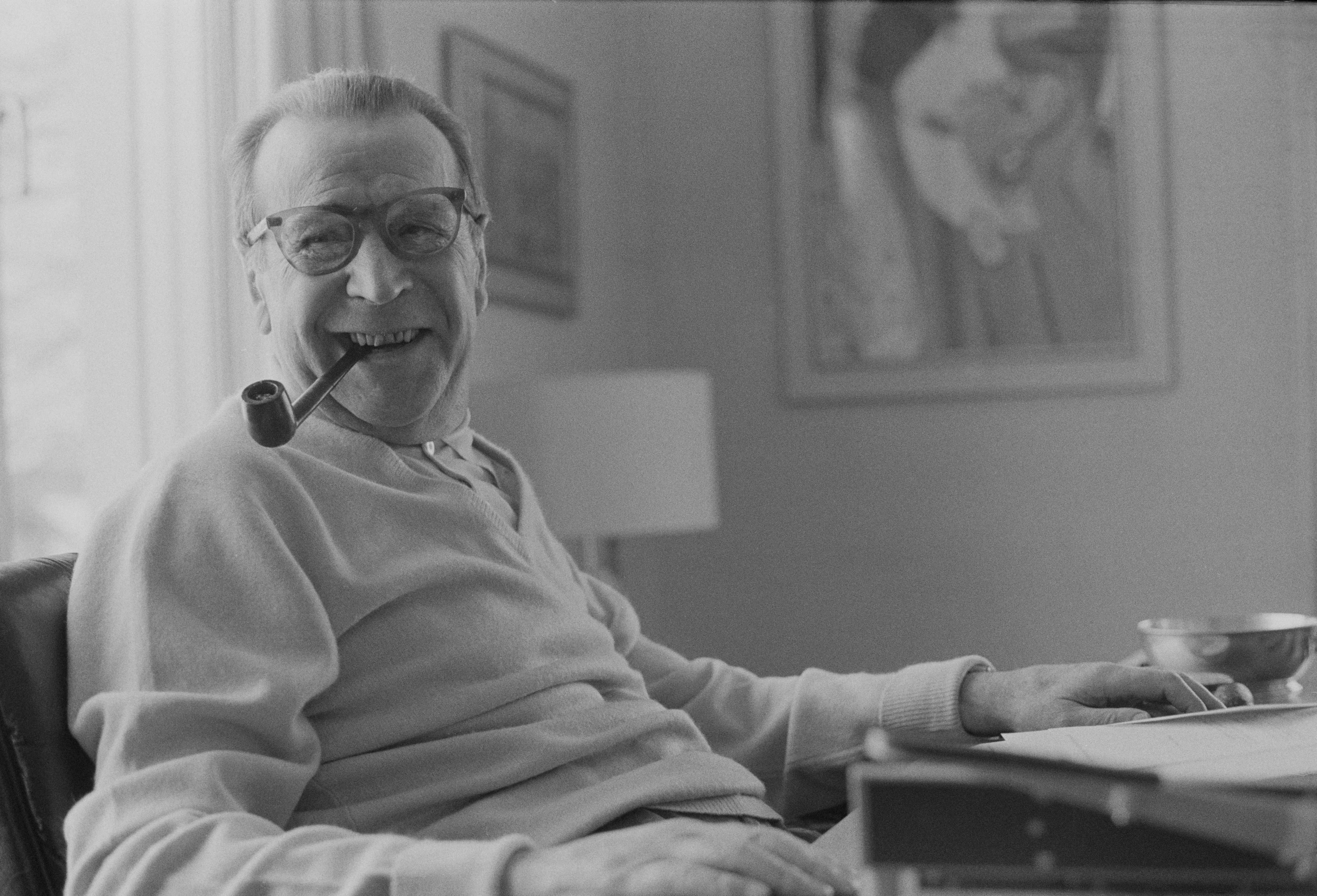

The Belgian novelist Georges Simenon is one of literature’s great paradoxes, a hyper-prolific fiction factory whose novels were nonetheless acclaimed by some of the twentieth century’s greatest writers. His productivity enabled fans to have a new novel to read every few months, yet they were not predictable; indeed, Simenon could be said to have reinvented the detective novel as we know it.

Though he also wrote more than 100 psychological novels he referred to as ‘romans durs’ (hard stories), Simenon is best known for his books featuring Detective Chief Inspector Jules Maigret, published between 1931 and 1973. Penguin has published new translations of all 75 Maigrets over the last six years, at a rate of one per month. (Previous translations were of mixed quality, sometimes even changing the endings.) This week the final novel, Maigret and Monsieur Charles, is released.

'It is the humanity of the Maigret novels that has made them last, and become so influential'

So Maigret will investigate a murder by speaking to as many people as possible (the books are heavily driven by dialogue), soaking up the local atmosphere with a beer or three, retiring to his home where Madame Maigret will unfailingly provide a delicious dinner, and he will ponder the case, imaginatively entering the mind of the suspect. Maigret, and Simenon, believed in the humanity of even the worst criminal, and preferred 'characters who were ordinary rather than exceptional.'

We do not, perhaps, read Maigret for the pleasure of fine writing or to linger over a page. Their addictive quality is certainly helped by their vast number, their relative brevity and the simplicity of their language (though the oft-repeated rumour that he used only 2,000 words in his writing is a myth). Nevertheless, it is the humanity of the Maigret novels that has made them last, and become so influential. Simenon received many fan letters not praising his plots or style but saying: “You are one who understands me” or “So many times I find myself in your novels.”

He was ahead of his time by writing crime as a product of human nature, and therefore often unremarkable. In the early novel The Two-Penny Bar, locals are more annoyed by a police roadblock put up after a killing than by the incident itself. In the late novel Maigret and the Killer, men playing cards in a bar don’t bother to investigate the noise of a murder outside.

That said, the Maigrets are still crime fiction, where tension is central. It was Simenon’s ambition to write “pure” novels which were “too tense for the reader to stop in the middle and take it up the next day.” (One of his techniques to ensure this is often to end chapters in the middle of a scene, so the reader wants to carry on.) Indeed, these are books which not only can be read in a sitting but which were written almost the same way.

'Alfred Hitchcock once telephoned him only to be told that Simenon was incommunicado'

Simenon’s productivity is legendary: he wrote one chapter a day, without interruption, and if he had to stop working on a book for more than 48 hours, for example through illness, he threw it away. He completed most of his novels in ten or eleven days, editing them only to 'cut, cut, cut' anything that he deemed too 'literary'. It’s reported that Alfred Hitchcock once telephoned him only to be told that Simenon was incommunicado as he had just begun a new novel. 'That’s all right,' said Hitchcock, 'I’ll wait.'

It wouldn’t be going too far to say that Simenon churned out his books – a French satirical newspaper said 'M. Simenon makes his living by killing someone every month and then discovering the murderer' – but he is critically adored too. André Gide was a lifelong fan (when asked which of Simenon’s many books to read first, he said, 'All of them') as were William Faulkner and Muriel Spark. Julian Barnes is such an admirer that he agreed to be the voice of Simenon in BBC Radio adaptations of several Maigret books, while Anita Brookner preferred Simenon’s non-Maigret thrillers, The Krull House best of all.

When Simenon wrote Maigret and Monsieur Charles, he didn’t know that it would be his last novel. But when he tried to begin his next book in September 1972, although he followed the same process as always by planning the characters on a manila folder in advance, he found that 'It would not work out.' The novelist’s flow had come to an end, and rather than mourn or force it, he announced his retirement from writing fiction. 'I was free at last.' He had ended his mature career as he began it 40 years earlier – with Jules Maigret.