- Home |

- Search Results |

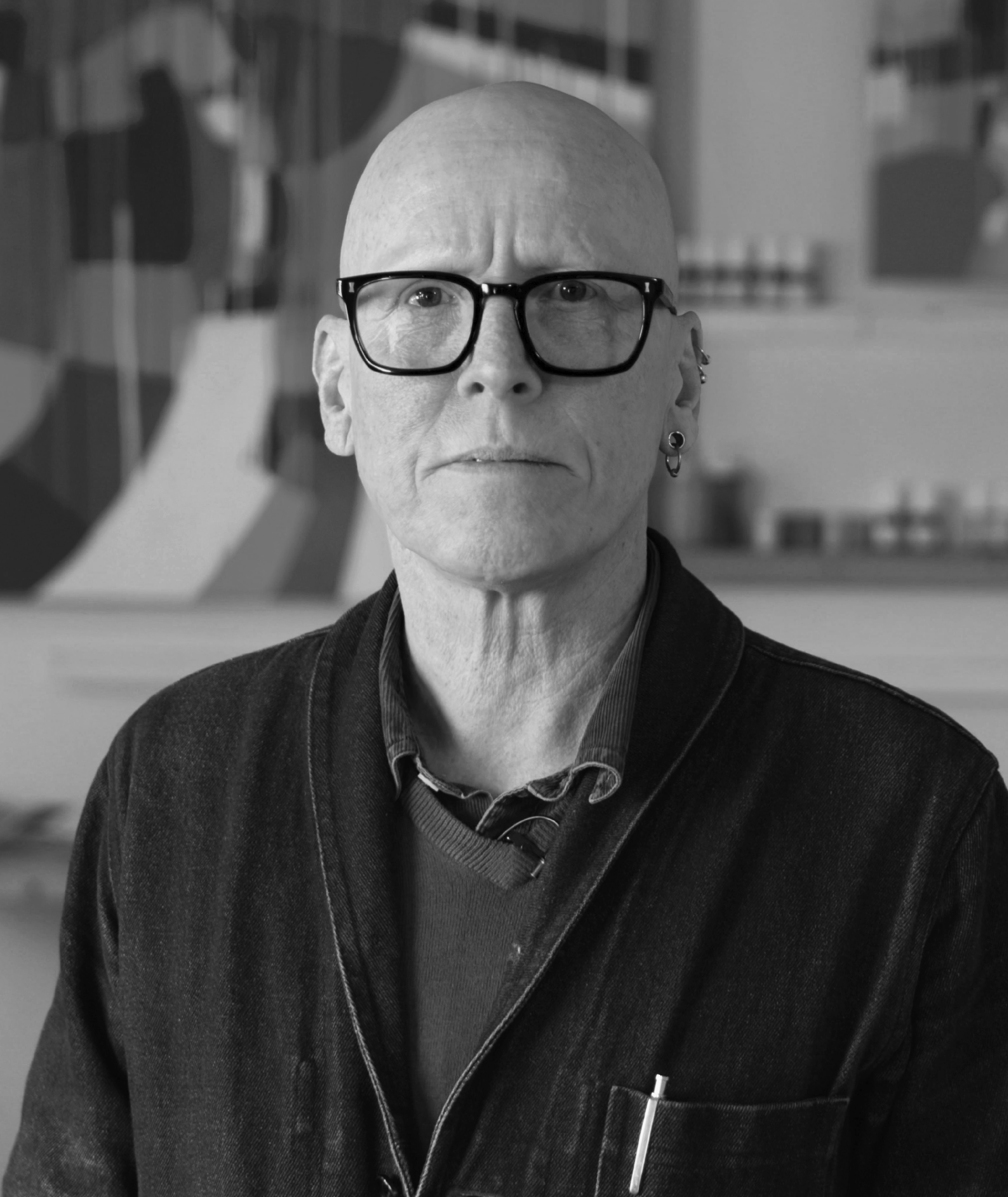

- Stanley Donwood: ‘I don’t know why people think I’m a paranoid recluse’

Stanley Donwood’s studio is nestled in the corner of a quiet mews, but he is nevertheless taking precautions for our interview, scrawling ‘BAD THINGS. PLEASE DON’T COME IN DANGER DANGER' on a piece of A4 that he tapes to the door.

'Bad things' have been a career-long fascination for the artist – best known for his collaborations with Radiohead and, more recently, nature writer Robert Macfarlane – and his latest book, Bad Island, is full of them. There are dinosaurs and unicorns, hounds and rats, factories and office blocks in flames, all meticulously carved into lino by Donwood over the course of two years and printed one per page. Through them, the reader sees, then lands upon, the island. What unfolds there looks like millennia of civilisation and destruction, which can be flicked through in a matter of minutes (there are no words) and returned to over the course of a lifetime. It's a depiction of the world that manages to be both terrifying and hopeful at once.

His makeshift 'do not disturb' sign hints at another side of the somewhat enigmatic artist who says he is often mistaken as a 'paranoid recluse'. In person, he is sprightly and wry, so enthusiastic to shake hands he doesn’t know which of our team to start with first. He is the kind of person who has been frantically heating up the stone-floored studio for an hour before we turn up.

Making Bad Island, he admits, was more exhausting than he anticipated. ‘When I got to about linocut number eight, I thought, “what?! I’ve got to do 10 times this many?”’ We talk standing next to all 80 of them, neatly lined up on boards and ready to be exhibited in East London later this month. A few rejects, which have figures on them, lie limply in a stack nearby. They’re the product of a realisation Donwood had half-way through the project, that he ‘didn’t want to make people the bad thing’.

Much of the work that Donwood has become known for – namely, the record covers for Radiohead, which he has been making since 1995, when their second album The Bends came out – has been the result of what he describes as failure. He has endless stories about the many false starts and 'accidents' that form part of his process. There was the paint-spewing dalek he wanted to use to create the artwork for the band’s latest album, A Moon Shaped Pool. When that didn’t work, he took all his equipment to the South of France where the band were recording and still struggled to come up with anything. It was such a ‘total disaster’, he considered having to get another job.

Before that, there was ‘eight months of horribleness’ inspired by an ambition to emulate Gerhard Richter, the famously proficient German portraitist, for The King of Limbs. Donwood says his attempts ‘ended up looking like dirty protests’. Some fans may know about the now-infamous ‘topiary cocks’ he wanted to make for the cover of Hail to the Thief (‘it turned out this wasn’t really an appropriate direction for Radiohead at that time’).

In previous studios, evidence of the above – and more successful expressions of Radiohead's visual identities – would have been scattered everywhere. But this one is relatively new and tidy (he only moved in last summer) and is mostly dedicated to Donwood’s current project: large, brightly coloured acrylic paintings that depict the landscapes of ancient hill-carvings around the UK. A representation of Eastbourne hill-carving, The Long Man of Wilmington, glints in gold leaf above my head. Donwood says he’ll spend our interview 'trying to figure out what [he’s] got to do with it.'

'I was, frankly, frightened of Stanley before I first met him....'

Bad Island isn’t Donwood’s first foray into storytelling. To dig around on his website is to find unexpected narrative projects including a poetic tribute to the suburban flotsam of East Croydon and a recipe for "Tear Wine" (eight pints of tears, sugar, general purpose yeast). Previous collections have been printed on hemp.

He admits that his artistic proficiency at school held certain benefits – his teacher let him bunk off games to paint, and 'it was an extremely good way of avoiding being beaten up. If you can draw stuff, the hard kids were really impressed' – but he nevertheless was torn between 'pictures or writing', like many, he says, of his university mates.

Among them was Thom Yorke, Radiohead’s frontman, with whom he would later conjure up his pen-name. Donwood’s real name is Dan Rickwood, and he has other guises besides. 'I like having different pseudonyms,' he says, which recently caused a bother when he attempted to pick up a box of Bad Islands from the post office which were addressed to the artist, rather than the man (they refused to accept his Wikipedia page as identification; there was a polite skirmish).

Donwood says that shifting from Dan to Stan helped him make sense of his work with Radiohead in the mid-Nineties, when he first started creating record covers as the band wrote and rehearsed their music, leaving his first baby at home. 'I felt like I was a split personality anyway, because I’d be changing nappies and doing the washing up and then hanging around recording studios and making artwork. It was very schizophrenic, I suppose.'

He’s been collaborating with Radiohead and Yorke, on the frontman’s solo projects, ever since. This suggests a kind of tacit exclusivity, although Donwood says it’s more that other musicians haven’t asked, aside from, in the Nineties, 'a well-known band' who were 'very interested in very serious drugs. Not very interested in artwork.' Preferring to work with a band that were, he 'chose poverty instead'.

Poverty, and the opportunity to define Radiohead’s public image over the years. The icy peaks of Kid A – inspired by footage of the wars in former Yugoslavia – and the bright colours of Hail to The Thief – road signs in Los Angeles – have become totemic, emblazoned on T-shirts and gig posters.

It was while he was creating a one-off newspaper to mark the release of The King of Limbs in 2011, that Donwood approached nature writer Robert MacFarlane. He was after a piece about trees, and it marked the beginning of a career-defining collaboration for both of them. 'I was frankly frightened of Stanley before I first met him,' MacFarlane tells me. 'I don’t know why, but I assumed that he'd be brooding, moody, prickly, hard to get on with. In fact, he's one of the gentlest and funniest people I know.'

At some point, Donwood earned a reputation as a recluse. Perhaps it's the visceral pessimism of his work (something he admits is 'quite glum', on the whole), or his slightly punky aesthetic – Donwood is bald, his ears are studded with hoops. He’s aware of the misconception, tickled by it, even. ‘First time I ever got interviewed, the guy was like, “oh I’m really surprised, I thought you were going to be a paranoid recluse”’, he laughs. Donwood named his next exhibition in honour of the assumption: 'The Dept of Reclusive Paranoia'.

'Robert MacFarlane and I cycled to Dorset and camped in a hedge for the night'

Instead, Donwood and MacFarlane embarked on Famous Five-style adventures that inspired their creative endeavours. Along with author Dan Richards, the three men 'cycled down to Dorset and stayed in this holloway. We trespassed and camped in a hedge for the night. And then decided, on a kind of whim, to make a book about it.' The result was published in 2013, as MacFarlane and Richards’ non-fiction book Holloway, which Donwood illustrated.

Six years later, Donwood’s landscape The Nether, something he describes as ‘a troublesome, troublesome painting’, featured on the cover of MacFarlane’s best-selling Underland. Then, in 2019, Ness emerged, a strange and eerie story created by MacFarlane and Donwood and the product of three years of conversations, ‘often had while swimming in the cold, inhospitable waters of East Anglia’. A third Donwood-MacFarlane book, Cider, is in the works, attributed to what MacFarlane calls ‘an important creative solvent for our working relationship’.

He gets up from the chair, which has intricately carved sides and was, Donwood said, rescued from a barn, to show me some of his ideas. With every turn of a sketchbook page, we flip through a moment in music history. One is covered in blue biro scrawlings about social media. ‘When we turned off all the Radiohead internet stuff [in 2016, the band deleted its entire online prescence ahead of the release of A Moon Shaped Pool]', he explains, ‘this was basically the pub conversation trying to do that.’

In the introduction to Donwood’s memoir, There Will Be No Quiet, Thom Yorke recalls the artist’s house as being 'just books', and Donwood says he had thousands piled up on the floor, on every subject from fungi to 'a whole load of really quite nasty skinhead books from the Seventies'. A man who doesn’t drive, he says he managed to read them all thanks to relying on public transport. He’s recently significantly culled the collection ('I’ve basically quit books now. There were too many'). But one, a book of medieval art which looks like it was published at least 30 years ago, has survived.

'It’s my cribsheet,' Donwood says. 'This is the inspiration for all of my woodcuts.' By chance, he had it with him when Cornwall flooded in 2004 and inspired Yorke to write his solo record, The Eraser. 'I just like the way it’s so crudely done,' Donwood explains. The cover of The Eraser is a deceptively primitive but nevertheless recognisable image of the London skyline being swallowed by turbulent, licking waves and heavy skies. A rat survives on a piece of driftwood. Aside from the black-clad sorcerer, the image could have been lifted straight from Bad Island.

Donwood is carving at the table now, with the same little chisel he’s used for all of his linocuts. He’s working on a sketch for a bigger project, which will depict Paris being 'destroyed by fire and flood in a quasi-medieval style'. It looks like satisfying work, easing out buff-coloured lino, skein by skein, to make a picture. Then he gets up, walks back a few paces to take in the painting he’s been considering all morning once more. 'Oh I think it’s not so bad after all!' he enthuses. Maybe sometimes, all the bad things need is time.