- Home |

- Search Results |

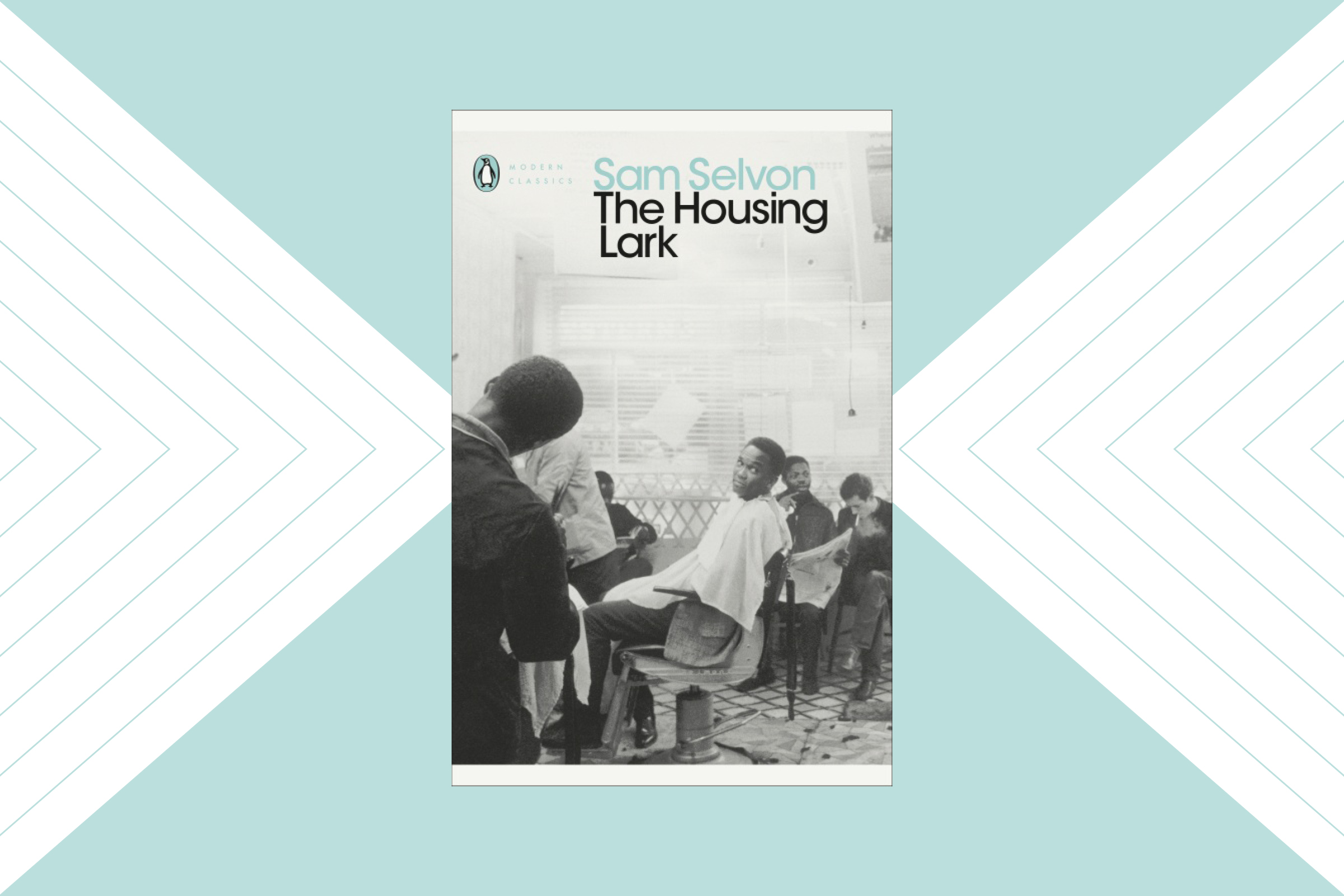

- The Housing Lark: Sam Selvon’s best – and funniest – underrated book

Although published 10 years after The Lonely Londoners, The Housing Lark seems to continue where Sam Selvon’s better-known masterpiece stopped. Originally published in 1964, there are similarities in theme, setting, and style, but Selvon shows far greater control, even restraint in The Housing Lark. This is undoubtedly the work of a more mature, more confident Selvon. So how has it been overlooked for so long by readers?

Selvon, a Trinidadian immigrant to Britain, has often been described as the originator of the template for the British immigrant fiction, especially focusing on characters from the Caribbean; in The Housing Lark he continues his exploration of these themes using a cohort of Caribbean characters living in Brixton. The novel’s launching conceit is simple, even predictable: a search for a home in 1960s London where most landlords won’t rent to Black lodgers.

Led by Bat, short for Barttleby, who is something of a leader in the group, the men and a few women decide to pool together money to buy their own house. However, the plot begins to thicken when Bat proves both corrupt and greedy – to him, and to most of the other men, the idea is just a lark. If, the narrator explains, the plan had been conceived in the winter, when there is less distraction and temptation, it might have worked, but in London’s hedonistic summer, it doesn’t stand a chance. The men want their money back, only Bat has already blown all of it.

The glue that holds everything together is Selvon’s sense of humour

Jean, a hustler, decides to change her ways because of her feelings for Harry. Teena, in the novel’s final and climactic scene, takes centre stage and saves the house buying dream, which is in serious threat of derailing. In her entreaties to the men to get serious about life, we come closest to hearing the voice of Selvon intruding, injecting a certain heaviness against the book’s generally comedic tone.

But the glue that holds everything together is Selvon’s sense of humour. Almost every single scene, or ballad, is loaded with comedy. The Hampton Garden scene, central and significant in so many ways – one of which is the bringing together of the whole Caribbean community in one place – is also noticeable because of its carnivalesque humor. By simply introducing the Caribbean community into this very English, very prim and proper setting, Selvon turns everything upside down and illustrates perfectly the idea of belonging, of outsider versus insider. As they take a tour of the royal palace they argue loudly, giving their own distorted version of history, afterwards they camp by the Thames, with their pots and rum bottles. “And this time the boys sprawl on the grass, shirt out, socks and shoes off, belts slackened, scratching and yawning and spitting and hawking and breaking wind, and now and then this bacchanal laughter ringing out: some women washing their pots and pans in the river, and the children dashing about like blue-arse flies and you hearing the elders shout: ‘willemeena! come away from there!’ or ‘albert! if you fall in that river today i leave you to drown!’”

Arguably the work of a great writer in his prime.

Helon Habila is an author. His latest book, Travellers, is out now.