- Home |

- Search Results |

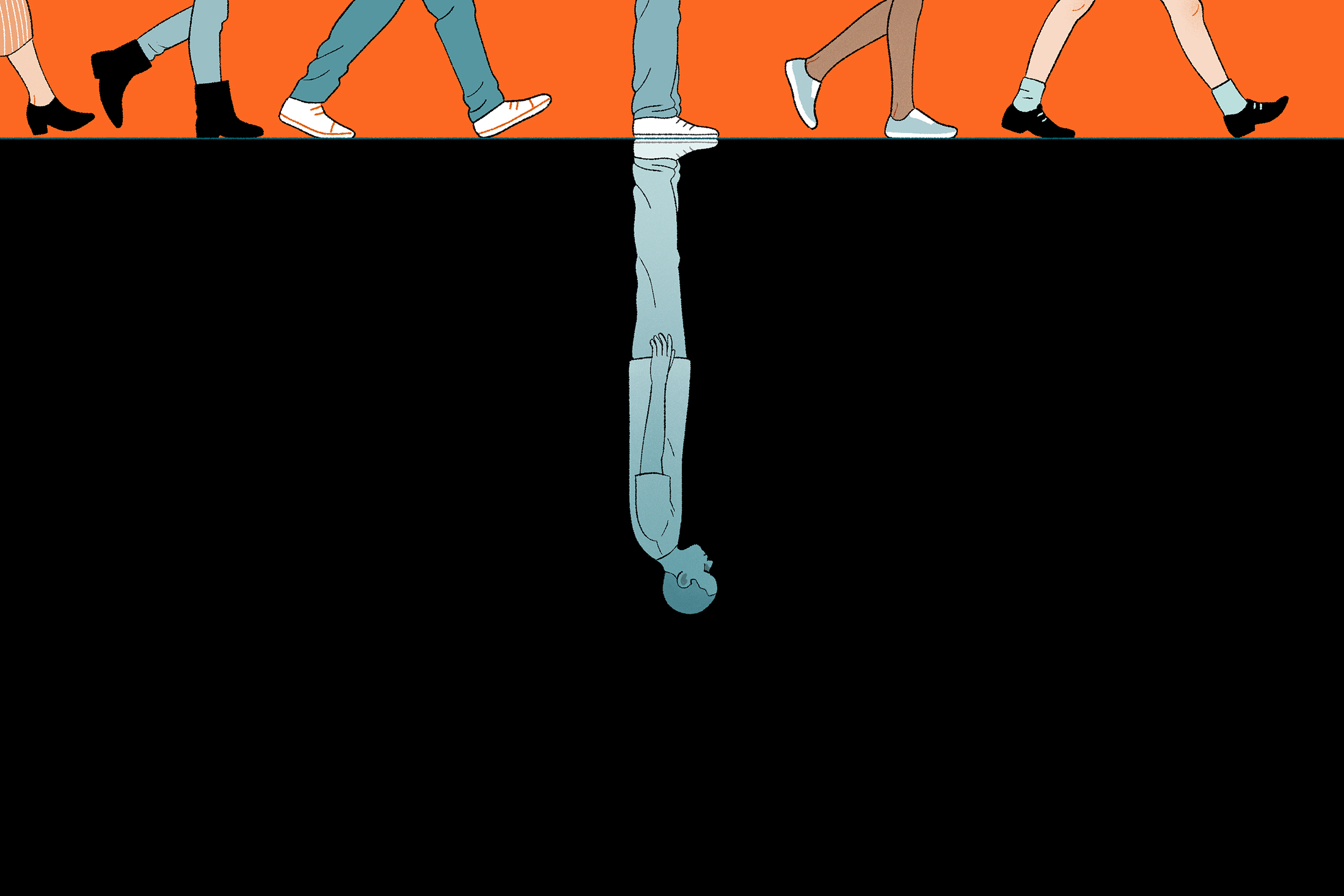

- Suicide is not inevitable: we can reduce it to zero

Suicide is not inevitable: we can reduce it to zero

In the first of Penguin’s Small Idea, Big Impact essay series, Cheer The F**k Up: How To Save Your Best Friend author Jack Rooke writes, on World Suicide Prevention Day, about the Zero Suicide model and training that could radically tackle the UK's mental health crisis.

My friend Olly and I met in uni in 2012, while studying Multimedia Journalism in London.

We were opposites. I was, as he described, a “fat gay”, and he was, as I described, a “lad’s lad.” We bonded over our love of hip-hop, Kilburn pubs and CALM (the Campaign Against Living Miserably), one of the UK’s most important mental health and suicide prevention charities. Once, when I was pretending to present a harrowing documentary about our campus library vending machine (“The sights this seven-foot box has seen students at breaking point, palpable despair, desperate for that next hit of Walkers MAX Paprika crisps and a sugar-free Red Bull”), Olly good-naturedly mocked: “You could be a fat, gay Stacey Dooley!”

Early on in our friendship we established we’d both struggled with various mental health issues, mine being caused mainly by losing my dad suddenly as a teenager and coping with the subsequent grief and depression. Olly’s issues were an illness, a set of misdiagnosed conditions; initially bi-polar, then borderline personality disorder, during which he faced the rigmarole of switching medications and being under observation. He was constantly trying to find the right balance. Throughout our short friendship, I knew Olly had experienced suicidal ideation – hence we both actively tried to fundraise for CALM, where I’ve been an ambassador since 2013.

And then in 2015, aged 27, Olly sadly took his own life.

In the immediate aftermath, I felt a combination of devastation and numbness; I was shocked and yet completely unsurprised. I’d always slightly worried about him. I’d heard that phone call with the worst news in my head before.

The following years I threw myself into trying to raise awareness of suicide prevention and CALM. I tried to fill the fat gay Stacey Dooley slippers Olly joked I should.

I presented a BBC Three documentary series about male mental health and suicide, which came out in May 2017. The day it first broadcast was the day I discovered the ‘other’ message inbox on my personal Facebook account. There were four or five messages from men who’d watched the show and wanted to share their stories of mental illness and suicide. As the show went on iPlayer and the Facebook trailer got more views, more shares and more people watched the show, I began to be bombarded on every platform with tweets, Instagram DMs, Facebook friend add requests from strangers. Some were just people saying they loved the show; some were wanting to share stories of their depression and suicide attempts; some were grieving a suicide; and some were parents desperately worried about their kids.

But the hardest to read were the many messages from younger people experiencing severe suicidal ideation, detailing how they were planning to attempt to take their life or telling me they’d bought certain methods online. It hit home just how dire our mental health crisis is in the UK.

In the immediate aftermath, I was shocked and yet completely unsurprised. I’d heard that phone call with the worst news in my head before.

The Facebook trailer for the show reached 5 million shares, so I swiftly took a hiatus from a social media platform I only really kept for photos of new babies and shit weddings I wasn’t invited to.

Over on Instagram I received a sweet message from a guy called Liam, a young chubby queer lad from Huddersfield who said that he’d been really struggling with depression and he’d loved watching another bigger gay man on TV who wasn’t just being taken the piss out of. I clicked on his profile, saw he made funny videos of himself in drag and so, naturally, I followed him back.

Six months later, after trying to distance myself from being fat gay mental health Stacey, I saw on Liam’s Instagram that his sister had taken control of his account. Liam had taken his own life, aged 22.

Now, there’s a feeling sometimes when you’ve been affected by suicide, that suicide in itself is inevitable. That it doesn’t matter how many celebrities ‘bravely’ open up, or how many documentaries/Lloyds Bank adverts/awareness campaigns try to shine a light on the issue – suicide is and always will be the end point for some.

The ‘zero suicide’ approach recognises there is no place for blame, but that healthcare facilitators must think always to the future.

Last year’s ONS stats saw a rise yet again in numbers of people taking their own life, and this is expected to rise in 2020 considering the immense pressure Covid-19’s lockdown measures have had on isolated, unemployed and vulnerable people. And let’s face it: you can’t exactly be a physical shoulder to cry on for your mates if that shoulder has a two-metre imposed distance around it.

While I was finishing writing my book Cheer The F**k Up: How To Save Your Best Friend, I discovered the 'zero suicide' model.

It’s a strategy of healthcare that originated in the US after frustration about existing approaches to suicide prevention. It’s now being adopted across the world, with the key belief that suicide deaths are always preventable. The idea of ‘zero suicide’ provokes a debate about how much more we may be able to do to avoid such tragedies and acknowledges that it’s hard to look back and see if something was missed. The approach recognises there is no place for blame, but that healthcare facilitators must think always to the future: to implementing varied types of therapy and treatment to help those most vulnerable.

Since Covid-19, the zero suicide movement and its various alliances have stepped up, aiming to provide “suicide screenings” for every potential vulnerable patient and fully assessing all the increased risk factors that the pandemic has created such as social isolation, job loss, health anxiety and their attendant stresses.

I believe that the zero suicide model needs to be adopted by the whole of our society now, in order to properly tackle the suicide epidemic.

I believe that the zero suicide model needs to be adopted by the whole of our society now, in order to properly tackle the suicide epidemic.

The UK Zero Suicide Alliance has taken this sentiment on. The ZSA wants to improve support for people contemplating suicide by raising awareness of, and promoting free online suicide prevention training, accessible to all.

The training, which takes between 10 and 25 minutes, aims to provide effective skills and awareness in how to recognise when someone may be experiencing severe suicidal ideation, how to talk to that individual and then help signpost them to urgent services and support.

After my experiences at CALM, losing Olly and seeing many young people choose to take their own life, the ‘zero suicide’ model is a small change whose implementation would render suicide as preventable – not inevitable.

What did you think of this article? Let us know at editor@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk for a chance to appear in our reader’s letter page.

Illustration: Bianca Bagnarelli for Penguin